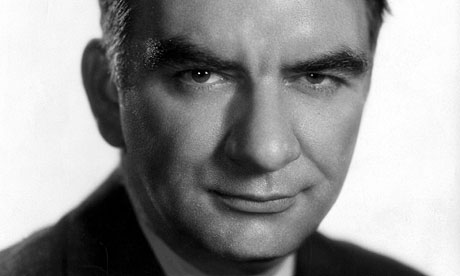

Hammett, Chandler, Cain: the modern mystery thriller starts with them. They are the godfathers of that sensibility that would come to be called noir which would, in time, overflow the printed page and onto the stage, the big screen, and eventually even to television. Identified primarily with mysteries, the concept of flawed human beings ethically tripping and stumbling in a moral No Man’s Land, equidistant between Right and Wrong, Good and Bad would bleed across genre lines. There would be noir Westerns (Blood on the Moon, 1948), noir war movies (Attack!, 1956), noir horror (The Body Snatcher, 1945), even noir melodramas like Cain’s own Mildred Pierce, adapted for the screen in 1945.

But they all started with what Hammett, Chandler, and Cain did on the page, and each provided an evolutionary step which took what had once been usually dismissed as a flyweight genre dedicated to colorful private investigators and clever puzzles, and turned it into literature’s dark star: stories that were less about cleverness than they were about recognizable, identifiable, relatable corruption.

Hammett came first, writing five novels between 1929 and 1934, but it was his third – The Maltese Falcon – which arguably had the greatest impact on the thriller genre. Falcon’s hero, private eye Sam Spade, redefined the P.I. hero. This was no intellectual superman, like Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, no bit of Agatha Christie whimsy. Spade was working class, a plodding pay-by-the-day dick, a knight errant loyal to a battered code of honor who realized there wasn’t always a happy ending, and that justice came with a price – even to the just.

But there was still a touch of the exotic to Spade, and, in fact, much of Hammett’s mystery fiction i.e. The Glass Key, The Thin Man. Hard-boiled and working class as Spade was, he was still in a world of not exactly run-of-the-mill hoods chasing after a jewel-encrusted statue.

Raymond Chandler introduced us to P.I. Philip Marlowe in the 1939 novel, The Big Sleep, and took him through seven more novels including the unfinished Poodle Springs in 1959 (Robert B. Parker would complete the novel in 1989). Marlowe was a more evolved Sam Spade: more contemplative, more philosophical, and, for that reason, a bit more world-weary and his battered code of honor even more battered.

But James M. Cain did them both one better.

He published his first thriller – the classic The Postman Always Rings Twice – in 1934 and followed it with a hot streak that didn’t peter out until 1951; a run which included his two other great works, Double Indemnity and Mildred Pierce.

There were no jeweled dinguses at stake in Cain’s novels, no family curses, and his heroes were not hard-drinking, chain-smoking, P.I.s or dogged cops. Instead, Cain’s protagonists were startlingly unremarkable: an insurance salesman and a stifled housewife in Indemnity, a drifter and the wife/waitress to a diner owner in Postman. They weren’t looking for The Big Score, they weren’t even particularly criminals. They were people who stood at the edge of the moral abyss and, in a moment of weakness, gave in to that dark impulse to jump in, and almost instantly regretted it.

Our pop culture friends over at Titan Books have uncovered James M. Cain’s last, unpublished novel, The Cocktail Waitress, released this month. Joan Medford is a typical Cain protagonist: a widow at 21; the accidental death of her alcoholic, abusive husband not quite accidental enough for one overeager cop; left broke; her young son in the custody of her less-than-sympathetic sister-in-law. Without even enough money to keep her house lights on, the unskilled Medford turns to pushing booze as a (if you haven’t guessed it) cocktail waitress.

And also, like any Cain protagonist, Joan Medford missteps. Judgment gets clouded by romance, by sex, by her desperation to do right by her son and win him back from her sister-in-law.

And also, like any Cain protagonist, Joan Medford missteps. Judgment gets clouded by romance, by sex, by her desperation to do right by her son and win him back from her sister-in-law.

For fans of hard-boiled fiction, and particularly for James M. Cain aficionados, it’s all here: the tough talk, earthy dames, shady fast-talkers, and a balancing act down the thin moral line with cold-hearted pragmatism on one side, outright greed and deception on the other, and temptation plucking at the wire.

But it should be said that for the non-die-hard fan, The Cocktail Waitress can be a disappointment. Though Cain was writing the novel in the mid-1970s and setting the story in 1960, the book feels woefully disconnected from its time. Women still talk about having a pregnancy “taken care of” but won’t use the word abortion; people still get their news primarily from the radio. Even Cain’s prose feels dusty and archaic. Strip out the few contemporary references, and Waitress could easily seem a work from the ’40s.

Titan’s boss fiction editor, Charles Ardai, generously shared some thoughts with us on James M. Cain, The Cocktail Waitress, and how Cain’s influence continues to filter through popular entertainment…

Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain – these are considered the holy trinity of mystery writing, in particular that genre dubbed “hard-boiled fiction.” What is it about The Big Three that makes them The Big Three, and what was distinctive about Cain’s work?

Cain, Chandler and Hammett were the first crime writers to elevate hardboiled or noir fiction above the level of simple genre entertainment and make something truly wonderful out of it, something that commented on human struggle and desperation and despair every bit as eloquently as the finest literary novel, while never losing touch with the genre’s two-fisted, crowd-pleasing roots.

Chandler and Hammett did it for the detective story, with their invention of Philip Marlowe and Sam Spade, respectively. Cain did it for the non-detective story, the story of people trapped in painful circumstances and committing crimes to get out of them, only to find themselves driven deeper than ever into suffering. All three men wrote novels that remain breathtaking reads more than half a century after being penned. Cain in particular harnessed the dark sexual energy of love affairs gone sour to produce some of the most chilling and visceral portraits ever committed to paper. So discovering a lost book by Cain – a new book, effectively – is truly an important find.

Cain is considered one of the founders of the roman noir, and that sensibility later spilled over into film: film noir. How did what Cain bring to the genre impact on other forms like film and, later, TV? Do you still see traces of it?

Cain’s impact is still felt in any drama that tackles adultery and the dark ends it sometimes drives lovers to. Any time you see a movie or TV show in which a sweaty couple post-coitally discusses offing the lady’s husband, taking the dead man’s money, and running away together, that’s Cain’s voice you’re hearing.

And more than that: Cain’s there in the atmosphere of so many films where California itself is a character and femmes fatale languorously drape themselves over settees, cigarette smoke trailing up toward a lazily turning ceiling fan. Cain’s there in the scene in the run-down diner by the side of the highway, where a waitress in a too-tight uniform trades wisecracks with truckers about burning the place down and running away with them, and she’s not serious, except maybe she is.

Cain’s gift to dialogue writers was the bank shot, the way two people can seem to be talking about something innocuous but really are talking about something else altogether, something that could get them arrested if they talked about it head-on. Cain’s influence is very much still there, even when today’s writers and directors don’t realize who it is they’re imitating.

Chandler and his private eye Philip Marlowe may have produced movies’ most memorable noir icon – the world-weary gumshoe poking into the dark underside of his clients – but it seems to me that Cain was closer to what noir was really about: impressively average people who make one misstep, then dig themselves deeper into a hole in their effort to get out of it. The Cocktail Waitress seems very much in that vein. Is that what Cain was all about as a writer?

Cain was definitely more interested in the people who commit crimes and the consequences it has on their lives than he was in the men who track them down. Even in Double Indemnity, where the relentless insurance investigator has a principal role, the focus is on the poor sap who gets lured into committing murder by the woman he hungers for. The police and other investigators are obstacles to be overcome, dangers to be feared, embodiments of retribution; they loom in the shadows and finally come and get you (and, often, kill you). But the “you” here is always an ordinary man or woman facing an extraordinary situation, and doing so without the benefit of a gun or a badge. It’s not the only noir story worth telling, but it’s a hell of a good one, and Cain excelled at telling it.

The only other author who came close was the brilliant Cornell Woolrich (author of Rear Window and so many other noir classics). Between Cain and Woolrich, you have a catalogue of the way ordinary people’s lives can be ruined, with an emphasis on The Man Who Should Have Known Better.

Considering the success – and classic status – of Cain adaptations like The Postman Always Rings Twice (1946) and Double Indemnity (1944), it’s surprising to me that more of his novels weren’t turned into films. I think Mildred Pierce (1945) was the only other one of his twenty novels to be turned into a film. Any thoughts on why that might be?

Well, the three books you named are his three best – it’s not surprising that they’ve also made the most memorable films. But The Butterfly (1982) became a movie starring Stacy Keach and Pia Zadora, the posthumous novel The Enchanted Isle was filmed as Girl In the Cadillac (1995), the 1956 film Slightly Scarlet was inspired by Love’s Lovely Counterfeit, and also in 1956 Serenade was filmed, with Mario Lanza as the opera-singer protagonist and Vincent Price in a supporting role. So there have been other Cain films – they just didn’t become famous the way the big three did.

There were also some TV and radio adaptations, and foreign films. And, of course, plenty of noir-ish movies that are heavily indebted to Cain, even if they don’t credit him as the official source of the material.

For a guy writing hard-boiled fiction, Cain seemed – for his time – extraordinarily sympathetic towards women. Mildred Pierce and Joan Medford in The Cocktail Waitress are women just trying to take care of their families, but forced to extremes by circumstance. Even the femmes fatale of Double Indemnity and The Postman Always Rings Twice have a sympathetic quality to them: women who made a bad decision and now feel trapped into going as far as murder to get out of it. You can’t even call Cora in Postman particularly greedy – the prize for all the conniving and murder is a roadside café. How do Cain’s women characters stack up against the noir standard?

It’s true that Cain’s women are sympathetic in a way the femme fatale types in crime fiction so often are not. That’s partly just the touch of a better writer, the sort who can put Shylock in a play but not without giving him the “Hath not a Jew eyes?” speech. Cain’s women aren’t two-dimensional because he wrote about three-dimensional characters, and that’s a big part of the reason (his) books hold up so well after all this time.

But it’s true that he seems to have a genuine touch of sympathy in his soul for the hardships of being a woman in the 1930s, ’40s, ’50s, when marriage could be the only path available, and yet could prove to be more a trap than an opportunity. His women were what they were because their circumstances left them with few or no other options, not because they were the female equivalent of mustache-twirling villains. These aren’t comic-book Cruellas toying with men for the sheer pleasure of villainy, or for perverse sexual satisfaction. They’re desperate people trapped in dire situations, grasping at a last chance for something better. Unfortunately, the “something better” comes at a terrible price, and turns out to be much, much worse.

Cain often dealt with extremely provocative themes which had to be tamped down in the film adaptations. In your estimation, how do the film versions of his novels stack up against their source material? Is Bob Rafelson’s 1981 adaptation of The Postman Only Rings Twice any closer to the original?

Every film adaptation alters the source material – it’s inevitable because the media are different, and also because any creative artist wants to put his own stamp on a work rather than just slavishly reproduce another artist’s work. So, filmmakers change the books they adapt, sometimes for the better, sometimes not. But that’s a matter of artistic choice. The phenomenon you’re talking about, of certain themes and incidents being too explicit for the movies back in the day, is a real one – and yes, the 1981 adaptation of Postman could go further than the Lana Turner version from 1946 in capturing the book’s raw eroticism. Still, is it “closer” to the book?

The erotic element is only one element, and by moving closer along that spectrum it may move farther away along another, such as the economic or philosophical. Cora doesn’t take up with Frank in Postman just because she’s horny and wants to get laid. She is horny; she does want to get laid. But her desires run deeper, and what drives her to murder is more than an itch in the pants.

In your Afterword to The Cocktail Waitress, you note that Cain’s career “…which had risen so meteorically in the 30s and 40s had fallen just as meteorically.” What was it about his work that had clicked so well with the reading public early on, and then had stopped working by the early ’50s?

I think these things just come in cycles. How many authors who were meteorically popular in the 1980s are still a hot number today? If Bret Easton Ellis penned a book in the ’80s or ’90s, it made headlines; he’s still around today, still writing, but the headlines have passed him by.

Cain similarly made a splash in his day, and the ripples kept spreading for a good ten or twenty years, which is nothing to sneeze at. But by the late ’50s and ’60s, Cain’s splash had been a generation back, and the new generation had writers of their own to get excited over.

Then, too, Cain really only published one book in the 1950s, Galatea, and it was a weak one, a real misfire. His next book after that didn’t come out for nine more years. A decade is a long time to go between books and still keep your name out there, especially in the days before the Internet and social media, when word-of-mouth traveled so much slower and less efficiently.

After publishing a dozen mostly excellent books in the ’30s and ’40s (and one in 1951, but let’s count that as the ’40s for our purposes), Cain began a dry spell that lasted the rest of his life: just one book in the ’50s, just two in ’60s, just two in the ’70s, and none of them at the level of his earlier work. It’s no surprise than the public’s excitement about him waned.

According to your notes in The Cocktail Waitress, Cain wrote that novel in the mid-1970s. The novel seems strangely disconnected from its time. Do you think one of Cain’s problems, in the latter part of his career, was that he’d fallen out of step with the times?

All old men are out of step with their times. They grew up in an earlier era and still view the present through the lens they ground in the past. Cain may have been writing The Cocktail Waitress in the 1970s, but it’s so very clearly not a book about a world that contains discos and Olivia Newton-John and Atari and Star Wars. Various events in the book date it back to the late ’50s/early ’60s – basically the Mad Men era – but in terms of atmosphere and flavor, it sometimes feels like it takes place in the high noir era — the James M. Cain era, if you will — of the 1930s or ’40s. Sure, there are passing references to hot pants and joints where the waitresses serve drinks topless…but the world of the book is the world Cain knew, the world of his prime.

During a trip to London in the book, the characters are talking about the wreckage in London left over from the Blitz. This is not a 1970s book. But does that make him out of step with his time? Or does it just make him a period novelist? The book is stronger for not being peppered with 1970s-iana. Reading it today, it’s not dated, it’s timeless. f it had been more ‘in step’ with its time when he wrote it, it may well be unreadable today.

It’s sometimes said Ross Macdonald took his cue from Chandler. In film and TV, as well as on the page, do you see anyone picking up Cain’s torch?

Macdonald definitely did pick up Chandler’s torch, and then Lawrence Block picked up Macdonald’s – the Matthew Scudder detective novels are the best and most important since Marlowe and Lew Archer. Who’s done that for Cain’s situations and themes?

Well, in the ’50s and ’60s, it was writers like David Goodis and Jim Thompson and Charles Williams and Gil Brewer, though no one of them burned as brightly. And today?

The best noirist working the Cain beat today is probably a woman named Megan Abbott, who has won the Edgar Allan Poe Award, deservedly, and has earned raves for each of her six books. She started out writing period noir fiction clearly influenced by Cain, and since has moved on to modern-day novels where the Cain influence is subtler. But it’s there, and no other writer working in the genre today quite captures the feverish intensity and the lineaments of desire quite the way Megan does. Her prose makes me breathe faster, the way Cain’s does.

That’s on the page. On screen? Obviously, what Matthew Weiner has done on Mad Men is extraordinary. At the movies, you see noir less often than you used to – I guess spandex-clad superheroes and animated, quipping animals rake in the bucks better than homicidal lovers. But every so often you get a good one. I still tell my friends to track down John Dahl’s The Last Seduction (1994), starring Linda Fiorentino. I think Cain would have been proud to call that one his own.

– Bill Mesce