Self-taught writer-director Richard Linklater was among the most successful talents to emerge from the new wave of independent American filmmakers in the 1990s. Typically setting each of his movies during one 24-hour time period – and with non-formulaic narratives about seemingly random occurrences – Linklater’s work explored what he dubbed “the youth rebellion continuum.” In the early 1990s, his debut feature Slacker was hailed as something of a manifesto for Generation X, and ever since, the filmmaker has earned a loyal fan-base world wide with such hits as Dazed and Confused, Before Sunrise. As big fans of the filmmaker, the Sound On Sight staff decided to vote on our ten favourite films from the director.

Note: There was two ties.

****

10: Suburbia

Originally a play by performance-artist Eric Bogosian (who also wrote the script), Suburbia is a character driven mood piece, which delves into the hearts and minds of a group of young adults. When Pony, a rock star, returns to his hometown of Burnfield for a visit, a group of his old high school friends organize a meet-up. Only Pony’s visit brings out the worst in his former classmates who get caught up in petty arguments, jealousy, envy, and depression. The characters in this film spend their free time hanging out at the Circle-A, a place where people temporary stop to stock up on goods and fuel up their cars before moving on with their lives. But Pony’s old friends haven’t changed and hover around the local gas station wasting time talking about all the things they want to do, but never actually do. The collaboration between Linklater and Bogosian seems almost preordained, as both artists previously found success with middle-class anomie and restless youth; but Linklater struggles at points with the jump from stage to screen. The script addresses many issues including resentment, addiction, fame and racial discrimination (to name a few), but some scenes dip into melodrama, and a handful just don’t ring true. In the end, Suburbia does little more than keep alive the ill-founded theory that the kids of Generation-X are without direction. Scored with a hip selection of rock and pop songs, pic has sharp lensing by long-time-collaborator Lee Daniel, and a strong young cast which includes Giovanni Ribissi, Nicky Katt, Steve Zahn, Amie Carey, Dina Spybey and Jayce Bartok.

– Ricky D

10: Me and Orson Welles

When I first saw this in 08 I was still pretty tainted by the Disneyfied images of Zac Efron so while I enjoyed the film, it fell low on my list. When I told a friend that we were doing this series he told me to take another look at it and see if it would raise from the lowly tenth place on my Linklater list. During my rewatch I finally saw the true brilliance of the performance of Christian McKay. McKay plays the manipulative genius with all the gravitas you feel the real Welles would have had. Claire Dains also gives a great performance and Zac Effron isn’t nearly as bad as you remember. Me and Orson Welles is a film that will get better with age especially if McKay’s career takes off.

Jonathan Marsellus

9: Tape

Richard Linklater’s third collaboration with Ethan Hawke, Tape further compresses the one night experiment of Before Sunrise into one night and one room. Based on the play by Stephen Belber, Tape uses its constraints to great effect as three old friends meet in a motel room and gradually unearth a painful past .

Like claustrophobic predecessors Rope, Lifeboat, or 12 Angry Men, the small, lone space makes performance and blocking all the more prevalent and Linklater’s cast of Hawke, Uma Thurman, and Robert Sean Leonard are up to the task.

What’s great about Tape is how fluidly it switches tone. The film might feel like a Neil LaBute play, a psychological horror film, or even – given its confines – a microcosm. At its heart though, Tape is a nostalgic, Diner-like drama, that marked Linklater as a bold filmmaker to watch.

– Neal Dhand

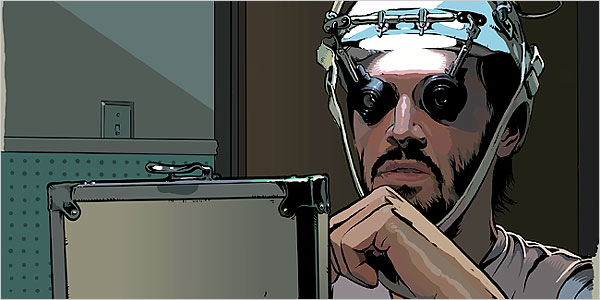

9: A Scanner Darkly

Dystopian sci-fi isn’t the first thing that comes to mind when you think of Richard Linklater, but his strengths—a certain hangout movie charm generated by the characters’ stoned conversations—give the world portrayed in A Scanner Darkly a lived-in quality rarely present in the genre. Taking place “seven years from now,” it is a world frighteningly similar to our own. A surveillance state perpetuates a failed war on drugs while a corporate superstructure manipulates it for profit, ignoring the destruction of human capital that results. The decision to use rotoscoping makes the addicts’ disintegrating personalities frighteningly tangible; the iconic scramble suits provide a disturbing visual metaphor. It is perhaps Linklater’s most undervalued film.

– Justin Wier

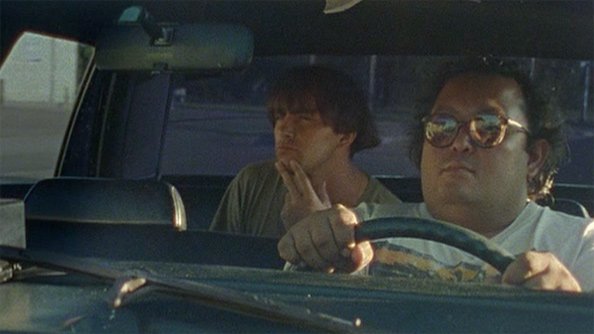

8: Slacker

Slacker came out around the same time that Douglas Coupland released his book, Generation X, and the young filmmaker became an instant spokesperson for an entire generation. While Generation X as a whole sometimes seemed to lack direction, its filmmakers devoted their early careers to making powerful statements about contemporary society and their generation’s role in it. Linklater (Suburbia, Dazed and Confused) emerged as the reluctant messenger for a generation labeled, packaged and sold as a defiant demographic dedicated to shredding whatever classification society tried to mark them as. Nominated for the Grand Jury Prize – Dramatic at the Sundance Film Festival in 1991, Linklater’s breakthrough feature is a key independent film of the early 90s.

Linklater stated: “Slackers might look like the left-behinds of society, but they are actually one step ahead, rejecting most of society and the social hierarchy before it rejects them. The dictionary defines slackers as people who evade duties and responsibilities. A more modern notion would be people who are ultimately being responsible to themselves and not wasting their time in a realm of activity that has nothing to do with who they are or what they might be ultimately striving for.”

– Ricky D

7: Bernie

Even though Richard Linklater has a diverse filmography, Bernie stands out as one of his oddest creations. Based on a true story and wedging in moments of mock documentary, it matches its main character by seeming syrupy sweet on the surface but hiding a darker edge. Bernie (Jack Black) has nearly boundless empathy, making a comforting funeral director, even befriending the wealthy, mean widow Marjorie (Shirley MacLaine), who is disliked by most in the small community. As it makes its dark turn, it makes both the film’s community and the viewer ponder ethical questions about whether the ends justify the means and how to responsibly handle wealth. For Black, who has often fallen back on playing versions of himself, this is finally a truly fresh performance.

Erik Bondurant

6: Before Midnight

Poignantly upending audience expectations about sentimental movie romance, the power behind Before Midnight is that it is built upon a trust two films deep. Before Sunrise and Before Sunsettugged at the heart strings for how well American Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and French Celine (Julie Delpy) were able to connect in such brief encounters. They seemed destined for each other even as their separate lives tore them apart. It turns out that from where we left off with them 9 years ago that they indeed did end up with each other. What then comes after the happy ending? It is an utter stroke of brilliance that the couple that fans have longed to be together for nearly 20 years completely skips over the honeymoon phase and is taken straight to enduring the complex, often bitter problems that any relationship is likely to suffer. Defiantly denying conventional satisfaction, director Richard Linklater pulls no punches in dealing with the concrete facts they now know about each other and how they might manage to make it work despite of their failings.

Breaking the mold of the other movies stresses how dramatically their lives have changed. All grown up, it is a rarity to be absolutely alone. Our couple coexists in a tension that teeters on erupting but has been kept at bay by the busyness of professional obligations and children. The intimate conversations that they treasured in the past for their brevity have become tested by time and routine. Their rapport is still good but now informed by anecdotes and lessons about each other. Continued philosophizing about love is at turns nostalgic and sad, colored by animosity from unresolved issues. The complexity of syncing personal and professional lives is no easy feat for anyone. Dwelling on the real work needed to sustain romantic love for someone you deeply care for is an indication of how the stars and director have matured. Written by all three of them (who in the past 20 years have known serious romance and had children) this film points to how real life problems with lovers are worked out. The fatigue in which they often regard one another is disheartening but accomplishes a thorough and important rumination on how elaborate relationships grow as time marches on. There is a an exceptional amount of suspense in Before Midnight if you’re invested. The end of the trilogy appreciates the audience’s emotional involvement, sometimes abuses it but finds a fitting way to say farewell.

– Lane Scarberry

5: School of Rock

Easily one of the most mainstream features of indie director Linklater, School of Rock is essentially an opportunity for Jack Black – whose prior roles were basically the well-meaning slacker – to become a bonafide rock god on-screen.

In order to get some extra cash, Black’s aspiring rock star Dewey Finn resumes the identity of his teacher roommate and takes a group of talented private school kids, getting them to help him achieve his dreams by entering a local rock group competition – all the while teaching them life lessons through classic rock.

Featuring a varied cast of comedic actors, including screenplay writer Mike White and comedienne Sarah Silverman, this musical comedy manages to combine heart and wit without delving too far into the clichés often linked family-friendly films (reluctant hero triumphs in the face of failure; insecure kid who hides their talent) – creating a surprise hit, with its child actors taking most of the praise from their established adult co-stars.

– Katie Wong

4: Waking Life

Waking Life is like a primer for all hip thoughts that are like-whoa, with the neat trick of never coming off as made by someone who’s doped up, or not putting their full mind and soul into the project for you.

While in his Before series the characters ruminate the streets of Europe to synthesize ideas of romance, here Richard Linklater takes it to the extreme and has its protagonist wander the streets of the dreamscape (or deathscape?) to synthesize ideas for the meaning of life. Yes, he uses a free-for-all “kitchen sink” structure that covers more pseudo-intellectual ideas than the French-iest of French films, but it is all with a calculated warm mood that makes it go down like red wine with a side of oxygen. Our hero walks in and out of random rooms, other people’s conversations, and deeper into his own psyche, seeing life as the tapestry it always is, but sometimes does not get to seem. All the while, the dynamic personalities of his helpers (many warranting or having movies of their very own) subliminally remind us of the human stakes behind the philosophical chatter.

Animated over live filmed actors, the movement of the piece feels extraordinary and weightless, an effect that prepares you to receive all the ideas that Linklater wants to wash over you. This is paramount to its success and not a gimmick, since, by its nature, some theories will hit some people as more truthful than others, and some will seem too far out to take seriously even for a moment. Judgment and critique, though, can only be considered antiquated in this Wonderland of psychedelic anecdotes and hypotheticals. In the end, Waking Life is a Rorschach test, but even more importantly, it is a rare respite from the artificial, only interested in digging at a truth (even if momentarily wacky or mundane) in order to help open us up to a greater, non-religious possibility.

– Michael J. Narkunski

3: Before Sunset

Possibly one of the more quietly-anticipated sequels in our generation, Before Sunset revisits the cinematic love story of Jesse (Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy), two young strangers who randomly met on a train and spent a day together in Vienna, and subsequently promise to meet up on a train platform six months later.

Audiences had to wait nine years for the outcome, as the two reunite by chance in Paris and spend an afternoon together in real-time, while teasing us with their ‘will-they-won’t-they’ relationship through their reflections of their encounter in Vienna. This is easily one of the most endearing love stories in film as we see Jesse and Celine’s relationship evolve into something more than a one-off meeting. Thanks to their collaborative efforts with the screenplay, Hawke and Delpy’s natural chemistry and easy dialogue puts other on-screen partnerships to shame and Linklater’s focused direction – shown through his use of Steadicam and long takes through the Parisian cityscape – beautifully captures a simple story that has continued to engage audiences for over fifteen years.

– Katie Wong

2: Before Sunrise

Before Sunrise tells the hopelessly yet innocently romantic tale of two twenty-something strangers, Jesse ( Ethan Hawke) and Celine (Julie Delpy) as they travel to Vienna and fall in love. Knowing they only have the night together, the star-cross lovers make the most of their time together with the upmost attention and solitude. By being alone, with the focus on these two characters only, the film becomes just as intimate as their evolving romance. As talkie as Linklater films are, Sunrise uses dialogue as a driving vehicle for both the lovers’ relationship and the audience’s point of view. As Jesse and Celine roam the Vienna streets, we stroll along holding their hand. As they play pinball, we are sipping beer alongside them. As they are star gazing while laying on a grassy field, we too feel the early morning dew on the back of our heads. Linklater masterfully evokes a visceral feeling of intimacy throughout the whole film. With his first instalment, the audience is transported back to their twenties, filled with emotions of optimism and uncertainty. Stabilizing its foundation of a great trilogy, Sunrise sets expectations high as a maturer relationship unfolds in Sunset and Midnight.

– Chris Clemente

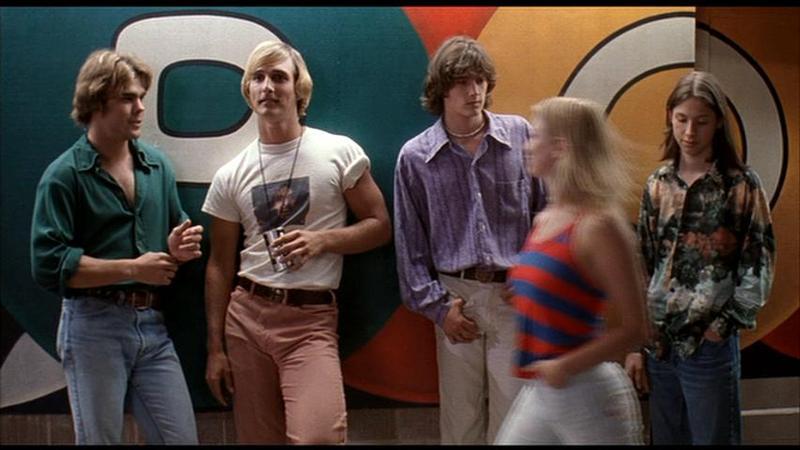

1: Dazed and Confused

Richard Linklater’s follow-up to Slacker, Dazed and Confused, flopped at the box office, but Dazed and Confused went on to become a huge cult hit. It’s set somewhere in suburban Middle America (filmed in Texas) on May 28, 1976, on the last day of school, and everyone’s looking for something exciting to do. First, however, the incoming freshmen students must spend the day fleeing from bizarre initiation rituals from paddle-wielding, abusive seniors – while everyone else does their best to get stoned or get laid. Set over the course of 24 hours, Linklater’s observations about the rituals of teenage life and about small town mentality is spot on – as is his attention to the smallest details of time and place. The biggest event for these kids isn’t so much the beginning of summer vacation, but rather, hazing, beating, humiliating, and simply taking out their frustration on those younger than them. All parties congregate at a huge beer bust in the middle of the woods, but amidst the keg parties, fights, dope-smoking, classic rock tunes, and endless partying, not much happens. The camera swerves between some two dozen youngsters and a handful of stories, but Linklater keeps everything and everyone on the same level. Incredibly entertaining, and without any hint of nostalgia, Dazed and Confused offers up an amusing commentary on life in high school, without ever breaking a sweat.

– Ricky D