Ben Gazzara died on February 3 of pancreatic cancer. An alumnus of the famed Actors’ Studio, he had a long career on stage, TV, and film. Not just long, but accomplished.

On Broadway, he was the original Brick in the Tennessee Williams’ classic, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and then he eclipsed that triumph with another powerful stage performance as a junkie whose habit poisons his relationship with everyone who loves him in A Hat Full of Rain.

His TV career launched in the early 1950s and extended through the next five decades. His small screen credits included roles on the landmark live drama anthologies of the 50s, such as The United States Steel Hour, Kraft Theatre, and Playhouse 90, and such acclaimed productions as cop drama A Question of Honor (1982), one of network TV’s first attempts to address the then detonating AIDS epidemic in An Early Frost (1985), and the epic mini-series, QB VII (1974). He starred in one of the classics of 1960s TV, Run for Your Life (1965-68), earning two Emmy nominations as a successful lawyer trying to live life to the fullest after learning he has just two years to live.

On the big screen, however, he never quite achieved the same stature he did on TV and the stage, in large part because – by his own admission – “I didn’t really take advantage of the opportunities,” though late in his career he became a valued character actor (he was a particular hoot as a porn king in the off-kilter The Big Lebowski [1998]). But his best film work may have been in some of his least-seen films; the movies he made for John Cassavetes, and the most popular of the three films they made together was Husbands (1970).

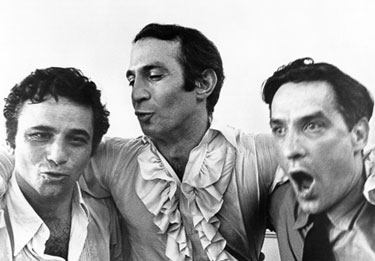

Cassavetes was a true art house renegade, taking acting roles in commercial movies to put together enough money to make his own, highly personal films. In Husbands, Cassavetes, Gazzara, and Peter Falk play three long-time friends who react to the death of another buddy with a midlife crisis bender of booze and a jaunt to London. Think The Hangover – but serious and for grown-ups.

Like much of Cassavetes’ work, Husbands has the shapelessness and shambling pace of life, the same sense of spontaneity, the same chaotic tumbling of the comedic into the tragic. It’s a demanding watch, but a rewarding one, almost uncomfortable at times in its feel of intruding into the real.

The heart of the movie is the give-and-go between the three leading men, and it may be one of the most honest and vibrant portraits of male friendship – with all its awkward intimacy and macho bullshit – captured on film. The bond between the three seems so damned real, it’s a surprise to find out that the three hadn’t known each other before Husbands.

Watching the film, seeing how open and vulnerable the three made themselves to each other, at the obvious chemistry among them, it’s no surprise they came out of the project friends. Gazzara would act for Cassavetes twice more, in The Killing of a Chinese Bookie (1976) and Opening Night (1977), and direct several episodes of Falk’s hit TV series, Columbo, including one starring Cassavetes as a philandering orchestra conductor.

But if you really want to see how closely tied the film brought them, go to YouTube and find them on an episode of The Dick Cavett Show being interviewed about the film. It puts Danny DeVito and his limoncello hangover on The View to shame. On the one hand, it’s appalling to see three grown – and obviously half-crocked — men cackling and falling over themselves on network television like kids farting in the back pew during mass.

On the other hand, it seems almost a scene from Husbands, and shows just how right the three of them had gotten it on film. Some things you can’t create; you can only hope to capture.

Husbands, Chinese Bookie, et al was not work Gazzara or the others did for fame and fortune. These were art house films before there was much of an art house circuit. Most people didn’t hear about them, even fewer went to see them. It was work done for the sake of doing; art for art’s sake. Film actors tend to be judged by their commercial successes and their visibility; not their willingness to explore the art. In that sense, Gazzara’s artistry was bigger than his career.