There are all kinds of producers: hucksters, hustlers, con men and schlockmeisters. Some are in it for the glory, some like to walk the red carpet with a starlet on their arm. For some, the biggest award is a box office hit and it doesn’t matter what kind of crap they throw on the screen to earn it. There are producers like Harvey Weinstein who will spend more money to promote himself to an Oscar win than he does on actually making the Oscar-winning film. And there are producers like Joel Silver who once said the only proper role for women in film was either as a dead body or naked.

And there are those – who, to be honest, may also have a touch of all of this – who are mainly driven by a desire to make good movies. Like Dick Zanuck.

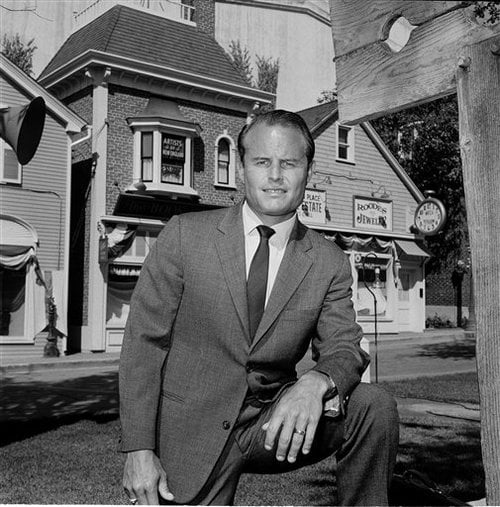

I don’t think anyone will argue – and certainly the obits which abounded after his death from a heart attack earlier this month – that Richard Zanuck was a class act as a producer. It’s there in his final score: three Best Picture Oscar nominations for The Verdict (1982), Road to Perdition (2002), and a win for Driving Miss Daisy (1989), as well as the Motion Picture Academy’s Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award (received with his one-time producing partner, David Brown) for the caliber of his body of work.

The movies were in Zanuck’s blood. He was the son of the legendary Darryl Zanuck, longtime chief of 20th Century Fox, accompanied his dad to the studio to watch rough cuts when he was still a youth, and would even assume the senior Zanuck’s studio throne in the 1960s (Zanuck, had left the studio in the 1950s, returned in 1962 after the success of his independently-produced epic, The Longest Day [1962] helped offset the studio’s money-hemorrhaging Cleopatra [1963]).

As a studio chief, Zanuck blended his father’s Old Hollywood sensibilities with a feel for the new young audiences of the 1960s, and was not afraid to challenge conventional wisdom. Instead of salutary war stories like The Longest Day, for example, there was the darker, more ambivalent war epic, The Sand Pebbles (1966). And when kids were in the streets protesting the war in Vietnam, Zanuck greenlit Patton (1970), a salute to one of America’s all-time great – and greatly terrifying – warriors. He saw sci fi not as low budget drive-in fodder, but the kind of Space Age-attuned storytelling which could bring young ticket buyers out in droves, and turned out the – for the time – state-of-the-art effects fest Fantastic Voyage (1966), and rolled the studio’s dice on what was, at the time, a daring, you-gotta-be-kidding-me project, Planet of the Apes (1968).

He still had a foot in Old Hollywood as well, as evidenced by The Sound of Music (1965), which may be one of the schmaltziest big studio musicals of all time. It’s also – adjusted for inflation – one of the biggest box office hits of all time as well.

In a biographic turn worthy of Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams, and the best episodes of Dallas, a couple of big budget flops got Zanuck booted from Fox and replaced by his father (even more ironic, it was his father, who on his return to Fox in ’62, had helped engineer Richard’s ascent to the head of the company; and in another irony, Richard Zanuck would pass on the anniversary of his father’s death).

After leaving Fox, Zanuck teamed with David Brown, whom he’d met at Fox, and they formed one of the most successful and respected producing entities of the last 40 years. Not every movie they produced was a gem (The Island, 1980), nor were they all hits (does anybody even remember Rich in Love [1993]?), nor were Zanuck & Brown morally immune to cashing in on a hit with a can’t-hold-a-candle-to-the-original sequel (Jaws 2 [1978], Cocoon: The Return [1988]). But the overwhelming body of their work – even when titles missed the mark – consisted of films which so obviously aspired to – above all things – be good: MacArthur (1977), Rush (1991), Mulholland Falls (1996), Deep Impact (1998), Big Fish (2003), to name just a very few.

In a business that has always been about safe choices, Zanuck and Brown consistently cut against the grain. They took a chance on a young TV directed name Steven Spielberg on a serio-comic couple-on-the-run tale with The Sugarland Express (1974), and without waiting for the box office tally (which, despite glowing reviews, was unimpressive), turned over one of the most valued properties of the time – the bestselling novel Jaws – to him and, in the process, changed the direction of Hollywood forever. With most of the majors exhaustively chasing after the youth market with the likes of Back to the Future (1985) and Batman (1989), Zanuck and Brown cut against the prevailing winds with hits headline by geriatrics with Cocoon (six top-grossing release of 1985), and the Oscar-winning Driving Miss Daisy (number eight in 1989). And perhaps nothing demonstrates Zanuck’s willingness to see how far he could push the commercial mainstream than his six team-ups with Tim Burton including the visually deranged Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (2005), nightmarish musical Sweeny Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (2007), and Zanuck’s final film, the campy Dark Shadows (2012).

One of my favorite stories about Dick Zanuck, and the one that I think captures what that essential part of him was as a – yes, you can call a producer this – filmmaker, is one I heard from Sonny Grosso, one of the real-life cops involved in the famous “French Connection” heroin bust.

Journalist Robin Moore had turned the case into a book, and a film adaptation had been pitched to Fox which turned it down five times. Finally, Zanuck agreed to take the project on, but there was a hitch: some of the participants were still haggling with executive producer G. David Schine (probably better known for his role as Roy Cohn’s protégé during Cohn’s infamous Red-baiting days working for Senator Joe McCarthy). By this time, Zanuck knew his days at Fox were numbered. In a conversation with Grosso, Zanuck pushed him to quickly make a deal “…because I’m gonna be fired in a few weeks.”

What I like about this story is that with his exit imminent, there was nothing in The French Connection for Zanuck. He had begun to see the potential in the project, but he knew the credit – as typically happens in such cases in Hollywood — would go to his successor. Zanuck just thought it was a movie that should be made. The French Connection (1971) would win five Oscars, including Best Picture, be one of the biggest grossing movies of the decade, and become one of the all-time classic thrillers. Zanuck’s name isn’t anywhere on the film, but he’s largely responsible it got made (as for karmic justice: Zanuck’s name has managed to stay connected to the movie, while G. David Schine would produce only one other film – the justifiably unremembered 1977 documentary, That’s Action! – and his connection to Connection is largely forgotten).

That kind of desire, that kind of belief that “good” can make money, is what distinguished Richard Zanuck throughout his career. It has always been a rare commodity in Hollywood, and not it’s rarer still.

– Bill Mesce