Brick

Written and directed by Rian Johnson.

imdb USA 2005 Edgar Chaput’s Review

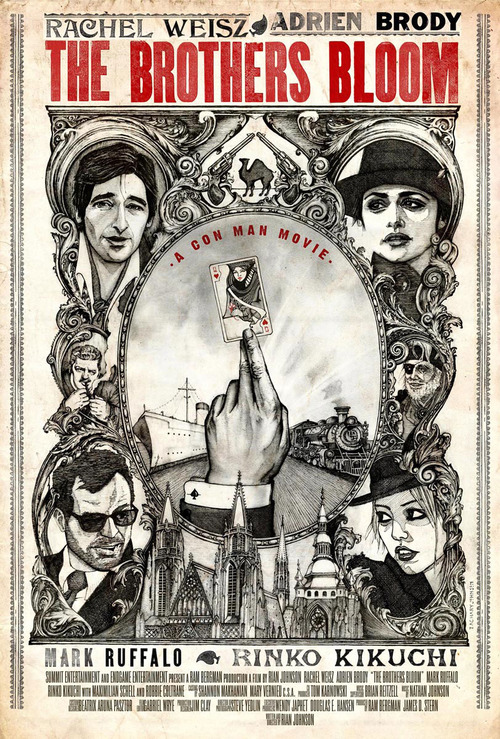

The Brothers Bloom

Written and directed by Rian Johnson.

imdb USA 2008

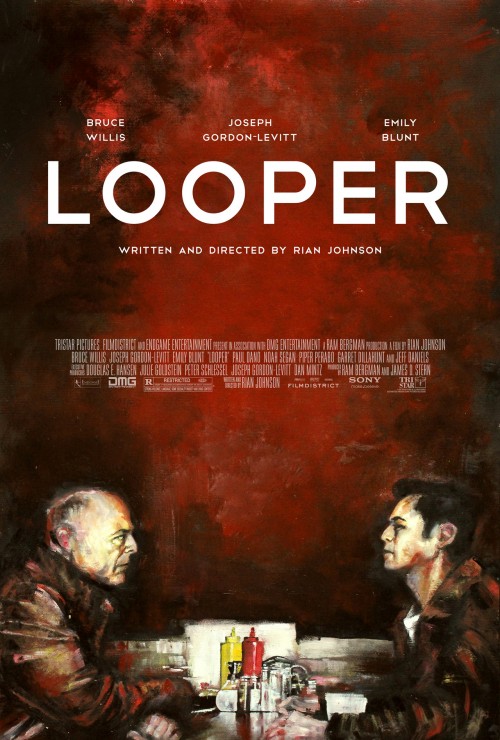

Looper

Written and directed by Rian Johnson.

imdb USA 2012 Sound on Sight podcast about Looper. Simon Howell’s review. Josh Spiegel’s review. Edgar Chaput’s review. Josh Slater-William’s review.

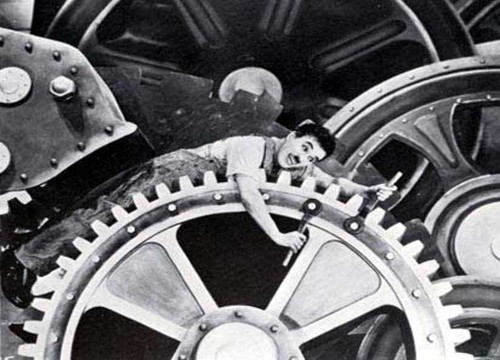

Modern Times

Written and directed by Charlie Chaplin.

imdb USA 1936 Sound on Sight podcast about Modern Times

*****

Rian Johnson has written and directed three films, each a carefully a constructed cinematic puzzle and each an exploration of a specific and completely different film genre: Brick (film noir), The Brothers Bloom (grifters), and Looper (time travel/science fiction). What is startling about Rian Johnson’s films – other than their impressive overall quality – is how similar the films are to one another despite coming from completely different genres, and, even more striking, how similar the protagonists are to each other.

“As far as con man stories go, I think I’ve heard them all. Of grifters, ropers, faro-fixers; tails drawn long and tall. But if one bears a bookmark in the confidence man’s tome, it would be that of Penelope, and of the brothers Bloom.” -Narrator (Ricky Jay) The Brothers Bloom

All three films are built around a playful love of language. Looper announces this with its opening line: “Time travel has not yet been invented. But thirty years from now, it will have been.” As a time travel story, Looper requires special language (Looper, Closing the Loop) and special grammar.

The Brothers Bloom is set in the world of the grifters who have their own special language. The plot revolves around a valuable stolen book – a collection of precious words, first mentioned by a con man named Melville, the same name as the writer of Moby Dick.

Brick is built on the conceit of a high school whose students speak the language of Dashiell Hammett’s hard-boiled noir universe. While this is completely artificial, it works for two reasons: first, by transposing the setting but leaving the language intact, we are able to truly hear the words – Rian Johnson is treating Dashiell Hammett’s language like that of Shakespeare – adding new resonance with a modern setting; second, there is a sense in Brick that the teenage hoodlums and the older crime boss The Pin (Lukas Haas) are simultaneously real criminals, but also modelling their criminal behaviour on the crime films that they have seen. Or as Abe puts it in Looper, “These films you’re imitating, they are copying other movies.”

This veneration of language (and the clever ways that Rian Johnson uses language in all of his scripts) saves all three films from what could be a key weakness – an over reliance on film narration, on telling instead of showing. Using voice-over narration is a tricky double-edged sword, but all three films manage to use voice-over narration just enough to tell us what we need to know, tell it to us in a creative way and then put the tool back in its box.

“He writes his cons the way dead Russians write novels, with thematic arcs and embedded symbolism and shit.” -Bloom (Adrien Brody) The Brothers Bloom

Language is an important building block for Rian Johnson’s films, because all of his protagonists to date are story-tellers: Brick‘s Brendan Frye (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) is telling stories to infiltrate The Pin’s criminal empire and take it down, The Brothers Bloom are conmen, by their very nature story-tellers and Looper‘s Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Bruce Willis) is literally trying to rewrite the future.

More importantly, they are all collaborative story-tellers – although those collaborations are frequently fractious. Brendan is assisted in his undercover work by the lies of others, but everyone who helps him has their own motive for doing so. Navigating these competing and contradictory agendas requires quick thinking and a hard head. Bloom has a difficult relationship with his brother Stephen (Mark Ruffalo) because Stephen tends to monopolize the writing of their cons, forcing Bloom to actually carry them out, leaving Bloom to long for “an unwritten life”. Joe has the most difficult collaboration because he is collaborating with his future self and the two Joes drive each other crazy pursuing their own competing – and frequently contradictory – agendas.

“God, I really loved you a lot. I couldn’t stand it. I had to get with people. I couldn’t have a life with you anymore. ” -Emily (Emilie de Ravin), Brick

All 3 of Rian Johnson’s protagonists are struggling with lost love. Brendan is still grappling with Emily dumping him when she is killed. Bloom falls in love with Penelope while he is conning her and loses her when the con literally explodes, tackling The Brothers Bloom‘s final con just to see her again. Old Joe is trying to change his own future to save the life of his wife, a wife he may never even meet if he’s not careful about how much he changes the present to rewrite the future.

“Ah, the folly of youth.” -Brendan Frye (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), Brick

Joe, Bloom and Brendan are all struggling with the blurry line dividing childhood from adolescence and adolescence from maturity. Part of that struggle is trying to figure out whether doing the wrong thing for the right reasons – or for love – can ever be justified. With each film, Rian Johnson ups the stakes.

In Brick, Brendan’s quest is kicked off by the murder of his ex-girlfriend and his actions – never all that heinous – can be justified using the same reasoning that an undercover cop would use. Arguably, the worst thing that Brendan does is conceal Emily’s body to give him time to catch her killer, but his argument for doing so is very persuasive, albeit in Hammett speak, “No, bulls would gum it. They’d flash their dusty standards at the wide-eyes and probably find some yegg to pin, probably even the right one. But they’d trample the real tracks and scare the real players back into their holes, and if we’re doing this I want the whole story. No cops, not for a bit.” There is also a sense of betrayal in the way that Brendan deals first with Kara (Meagan Good) and then with Laura Dannon (Nora Zehetner), a call back to the way that Sam Spade dealt with Brigid O’Shaughnessy in Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon and for the same reason, “When a man’s partner is killed, he’s supposed to do something about it.”

In The Brothers Bloom, Bloom is forced to choose between the woman he loves, Penelope Stamp (Rachel Weisz) and his brother. The film implies that Stephen forces Bloom to choose Penelope, a mature extension of their original con which was designed to get Bloom to talk to girls for the first time, but Bloom must still live with the guilt of that choice.

“We both know how this has to go down. I can’t let you walk away from this diner alive. This is my life now. I earned it. You had yours already. So why don’t you do what old men do and die?” -Young Joe (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), Looper

If the choices in Brick are difficult and the ones in The Brothers Bloom are heart-breaking, the choices in Looper are the stuff of nightmares. The conflict between Old Joe and Young Joe is a generational conflict turned to 11. Young Joe is perfectly prepared to murder his older counterpart from the future to preserve his present. “Loopers aren’t known for their forward thinking,” Young Joe notes dryly early in the film.

Old Joe doesn’t make any of this easier for his younger counterpart. When he leaves Young Joe unconscious with a note suggesting that he run, Old Joe neglects to leave any of the gold that he was using as a bullet-proof vest. Penniless, Young Joe is almost forced to sneak back into the city, back into harm’s way to try and steal back some of his Judas silver to give himself money to run with.

The conflict between Old Joe and Young Joe is almost like a fight between a producer and director over the final cut of a film. Old Joe has the advantage of experience and knowledge of the future; Young Joe has the keys to the editing room. Young Joe can make decisions and take action in the present that will permanently affect Old Joe – like scarring Beatrix on his arm to force Old Joe to meet him in the diner.

Making things even more intense is the reason that Old Joe has come back in time 30 years from the future. The Rainmaker, the future’s criminal overlord, kidnapped Joe to send him back to the past where his younger self would kill him and “close the loop”. In the process, Old Joe’s wife (Summer Qing) was (will have been?) killed by a stray bullet. (Since Old Joe kills the thugs who kidnapped him and murdered his wife, he comes back in time because he chooses to, not because he is forced to.)

Since Old Joe knows when and at what hospital the Rainmaker was born, the film literally turns on the normally hypothetical “Would you kill Hitler as a child?” question, ratcheting up the moral quandary by giving Joe three children born in the hospital on the same day, one of whom might grow up to become the Rainmaker, two of whom are innocent.

“There is no such thing as an unwritten life, only a badly written one.” -Penelope Stamp (Rachel Weisz) The Brothers Bloom

The standard knock on Rian Johnson’s films is that they are cold and mechanical, clockwork plots manipulating clockwork men. There is no denying that what makes Brick, The Brothers Bloom and Looper dramas in the Greek sense is that their protagonists are trapped in a Kobayashi Maru scenario, their only possibility of escape a sacrifice: of love, of loved ones, of oneself.

But the key to Rian Johnson’s clockwork men is the image of Chaplin’s Tramp in Modern Times: trapped in the gears with a wrench in each hand, cheerfully building his own prison. Brendan, Bloom and Joe are like the proverbial monkey with its hand trapped in the jar, imprisoned in Johnson’s clockwork machinery because they refuse to let go of their wrench. Rian Johnson’s protagonists are men of flesh and blood; his clockwork worlds are greased with that blood… and their blood is hot.

– Michael Ryan

Brick, The Brothers Bloom and Looper posters by Zachary Johnson.