Written by Edgar Wright and Michael Bacall

Directed by Edgar Wright

USA, Canada, 2010

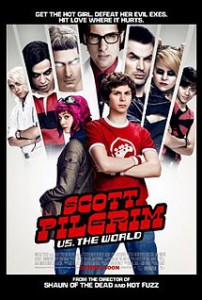

If a big-budget blockbuster opens, and nobody goes to see it, does it make a noise? In the case of 2010’s Scott Pilgrim vs. The World, an ambitious adaptation of Bryan Lee O’Malley’s cult favorite graphic novel infusing youthful music obsession and arcade beat ‘em up nostalgia with a rich subtext surrounding young love’s fatality, the answer is a big yes. It also comes with a mood of “bright lights, big witty” and one of the most notable on-screen displays of visual flair in recent memory by a director clearly born to be a showman. Pity that most of the talk that went on at the spiritual after-party was why it failed quite so badly.

Such conversations come across as being almost disrespectful, much in the same manner that a star’s comeback can be devalued by focusing on the reason they had to rise from the flames in the first place. The mystery isn’t really that profound, and in retrospect, the prospect of this movie failing to make back its own budget could even be deemed predictable. The world’s cinematic community had more or less fallen out of love with Arrested Development alumni Michael Cera through over-exposure and the resultant exhaustion by the time the film was released, meaning a loss in star power. Wright, despite being highly rated by executives following his work on Shaun of the Dead and Hot Fuzz, didn’t share the same reputation among the public. He was, after all, hidden in the shadows of Pegg n’ Frost. The graphic novel’s fan base, though large, also wasn’t significant enough to recoup the $60 million budget alone. Most crucially, even now, as a film, it is almost impossible to define.

Ironically, the inability to define the film simply is the very element that makes it so distinctive and so deserving of love. Scott Pilgrim, archetypal geeky trendy kid from Toronto, meets the love of his life but has to defeat her seven evil exes in mortal combat to claim her. In genre terms, this clearly is a fantasy action adventure. Except it isn’t, since although Pilgrim exists in a world fantastic in its non-reality, it doesn’t follow the convention of adventure and cannot be deemed an action movie despite its fight scenes. It also should be considered as a comedy or black comedy in the same manner as Wright’s earlier films, and owes a lot to the conventions of romances, yet often acts as a subversion to its foundation and has a large dose of satire for each category it touches; drama is played ironically, comedy is played as wisecracking comic relief, action is used with irreverence, romance is nitpicked and turned on its head, adventure is rooted in one location and the fantasy is only employed partially. If you can find a pithy way to sum this up and sell it to a wide audience, you should be earning a seven-figure annual sum for Universal’s marketing department.

As proven by other graphic novels, most notably Alan Moore’s Watchmen, on-page visual storytelling usually has the ability to convey more than cinema can and doesn’t suffer the same backlash from breaking the basics of storytelling in the same way that novels are allowed to adhere to any structure or non-structure they desire in the interest of their vision. The only way to tackle something as a chaotically entertaining and necessity driven as O’Malley’s story is to employ those same principles. This tale simply couldn’t have been told straight. While this may have caused Scott Pilgrim to be somewhat unviable on the market, it also serves as its main strength.

Think to the first fight scene, in which Scott is confronted on-stage during a battle of the bands by the first of Ramona Flowers’ evil ex’s, Matthew Patel (Satya Bhabha). In a film that has already shattered conventional storytelling method and the fourth wall in establishing the set-up to the quest, this is the first time that it simply does away with a set sense of physical reality. Patel arrives through a window, swoops down and engages in Matrix Revolutions-esque combat, all while Scott’s friends watch on as if seeing a regular bout of fisticuffs. Then, inexplicably, Patel bursts into a Bollywood musical number. The closest thing to an on-screen comment on this bizarre moment is Scott’s sister’s (Anna Kendrick) bemused “What?!” reaction (an appropriate response to much of the movie). When Scott finally defeats Patel, the crazed Indian avenger is rendered into a pile of coins which the erstwhile hero collects. On paper, this is a bad dream of excess usually expected from a wannabe teenage scriptwriter whose sense of self-discipline is dwarfed by the bag of weed sitting next to him. On-screen, however, it is thrilling and visceral enough that one simply doesn’t care how nonsensical it truly is. Happily, it also sets the tone for what is to come. Every fight Scott is thrust in to shares this video-game style and impertinence.

It also makes humorous yet nightmarishly surreal interludes all the more in-character and less distracting. Brandon Routh’s hilarious cameo as big time none-too-bright rocker Todd is brought to a close by the arrival of two time- and space-defying ‘Vegan Police’ super cops (one of whom is, strangely, played by Thomas Jane) who seem to have been imported from an Alex Proyas movie. Scott chooses to escape an awkward confrontation with recently dumped girlfriend Knives Chau (Ellen Wong) by throwing himself through a glass window no more than five feet away from where she stands, none the wiser. This getaway is facilitated by Scott’s roommate Wallace (Kieran Culkin), who spends the movie either cracking deadpan remarks and insults or successfully seducing every male character he comes across within the space of a couple of minutes. One of Scott’s exes, Aubrey Plaza’s foulmouthed Julie, has the ability to bleep her regular cursing without explanation. Scott defeats skateboarder-turned-megastar Lucas Lee (Chris Evans) by challenging him, in front of some girls, to grind down an impossibly long and treacherous handrail. The attempt sees Lucas careen out of control, fly through the night sky and…explode. And, perhaps most amazingly, the big bad is played by…Jason Schwartzman. “What?!” indeed.

The fact is that Wright, who is the real star of the film rather than the unchallenged Cera, manages to make these events part of the fun where they could easily have been disastrous. The arguments that the ideas on script make themselves are redundant when you consider that segments of the film lacking dynamic set pieces are presented and processed with a psychedelic style in pacing, framing and focus. The three-way battle between Scott, Ramona and Mae Whitman’s Roxy is one of the best directed fight sequences seen in years, despite its overarching measure of comedy. And when it comes to the quiet drama scenes, Wright tones down the frenetic pace and uses the un-reality to convey mood and tone. Scott sitting sadly alone in a play-park is given extra dimension by surrounding the set with empty darkness, suggesting that there literally is nothing else in the world but his despair.

Of course, this emotion doesn’t stay for long in the interest of keeping the momentum going, as the scene is clearly cracked by further jokes and a uniformly amoral sensibility. This allows the real heart of the story to exist behind the fantastical presentation, subtext remaining just that. Although the film stays true to its style and attitude, it is ultimately telling a very simple story and one that doesn’t skimp on unglamorous complexity. Truthfully, despite the retro video game asides and comic-book take on narrative progression, Scott Pilgrim is just a story about a boy who has been hurt many times falling for a girl who has been through the same and how difficult it is for the two to overcome their pasts to be content as a couple. Neither is perfect by any means, with Scott in particular managing to be an unreliable narrator in a film that is mostly shorn of protagonist-dictated perspective. The fact that he has been plenty cruel and immoral over the years despite the veneer of nerdy sweetness means that we aren’t insulted by a goody two-shoes trying to get what he wants archetype. In other words, complexity. It’s a good thing.

Of course, subtext is subtext. It merely adds to the appeal of a film that is, at its heart, a stylistically pleasing and adrenaline fuelled assault on the senses that in many ways is merely warping its reality in order to better convey how events ‘feel’ to a beleaguered main character. The same story told conventionally would be nowhere near as approachable or memorable, and would have lost something in adhering to realism. In a perverse and unquantifiable twist on logic, doing away with anything that even vaguely resembles reality actually enhances the visceral impact of the story. To Scott, overcoming Ramona’s back catalogue of nasty and strange feels like battles to the death with an array of fantasy characters and caricatures. As a comic book, video game, and punk music aficionado, his life is tinted with styles and trappings of each. So that’s what we see, not the dull reality.

The fact that this perspective is so artfully and wonderfully captured by Wright and played out in delicious manner by a superb cast is the icing on the cake. As far as immersive entertainment and spectacle go, Scott Pilgrim vs. The World didn’t fail. And it didn’t fail with quite some noise. A cult classic it may be, but thanks to its own merits, that pesky adjective can be disposed of.

-Scott Patterson