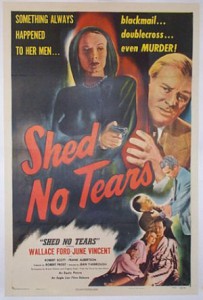

Written by Brown Holmes

Directed by Jean Yarbrough

U.S.A., 1948

Edna (June Vincent) and her much older husband Sam Grover (Wallace Ford) have cooked what they believe is the perfect plan to live happily together with a handsome sum. Despite that Sam’s career floundered, his insurance is an enviable amount, hence they opt to fake the husband’s death to in order for Edna claim the bounty of 50,000$ before meeting up with hubby in Mexico. What Sam fails to realize is that Edna already has another beau, Ray Belden (Mark Roberts), with whom she actually intends to split the money. Complicating matters is, first, Sam’s son Tom (Dick Hogan) who refuses to believe the police report concluding that his father’s death was accidental. Secondly is the private eye Huntington Stewart (Johnston White), commissioned by Tom to snoop around to find out what he can about his father’s passing but who would like to touch some of the money as well…

Shed No Tears, directed by Jean Yarbrough is the sort of lark with which the viewer can have a lot of fun provided they can temper their expectations to a certain extent. There are no major stars of the era and the overall plot has a ring of familiarity, what with a series of characters all trying to pull the strings behind one another’s back with their eyes on the ultimate prize. In other words, noir fans may easily claim this entry as lower tier noir. What it lacks it originality of plot it truly makes up for through sheer energy of the cast and acute visual eye from the director, sometimes in rather unexpected ways, therefore making Shed No Tears (which is a very cool title, by the way) an extremely pleasant surprise.

Jean Yarbrough pulls out as many stops as he can to provide the endeavor with all the panache he can muster from the director’s chair. No Tears, despite not benefiting from any restoration process other more notorious classics of the era have in recent years, has a fantastic look to it. Yarbrough brings a lot of style to the lighting and editing, specifically with fade ins and outs, such as when Sam, away in Washington as he impatiently awaits his wife’s arrival, reads a letter she has sent him, with the two images of Sam reading the letter and his POV of the letter itself bleed into each other in the same shot as June Vincent’s salacious voice over narrates the text to the audience. Other attractively stylish moments that juggle impressionistic light and shadow, such as when Tom, increasingly flustered and doubtful of the private eye’s trustworthiness, slaps the latter around, an attack only seen as shadows dancing against a nearby wall. Yarbrough was by no means a household name (perhaps best known for directing a decidedly loony 1940 Bela Lugosi vehicle, The Devil Bat), nor may the mention that he directed this effort stir the passions of many a cinephile, but this particular film definitely is evidence of his gusto.

Another aspect that deserves mention is the cast, who put in at times particularly theatrical, calculated performances. It makes one wonder if the filmmakers involved had taken some notes when viewing other genre entries of the time and subsequently directed the actors to play their parts by emulating popular styles. In that regard, some of the performances almost have a forced feel to them, but never so much as it comes across as an utter farce either, thus finding an unexpected middle ground between earnestness and parody. The unique tone is set from the very first scene when Sam and Edna drive away after setting a hotel room on fire as part of their scheme to fake Sam’s death. A lot of the dialogue, specifically when they part ways, sounds like the sort of lines that have been exchanged in a million other thriller between lovers, yet June Vincent and Wallace Ford are so good at saying them that the lack of originality matters little. In fact, nearly every performance in the movie is straddling that fine line.

Nearly everyone, that is, save Johnston White as the foreign born private detective who tries to swindle a fair number of potential victims throughout the picture. As in Born to Kill, which also features a streetwise detective who was clearly from the same parts as the other main characters, Huntington Stewart is a completely different ball of wax, even more so than the private dick in Born to Kill. White injects the part with such aristocratic pomposity, such cockiness that it becomes next to impossible to actually dislike him. ‘Over the top’ barely even scratches the surface when trying to explain what the actor is aiming for. Wryly funny and instrumental in building up the film’s themes of greed and mistrust, Huntington Stewart is a one of a kind creation, not exactly belonging in any universe so why not simply enjoy him as he weasels his way around in this one.

There are equally strange moments when Yarbrough’s film errs for the briefest of moments in utter comedy. Take for example when one of the prime  characters turns up dead in their apartment. The police investigate the premise and ask the landlord some queries. When the nonchalantly saying the place is now vacant, one of the surrounding officers claims it as just the sort of place he was looking for and asks his captain permission to talk to the landlord privately.

characters turns up dead in their apartment. The police investigate the premise and ask the landlord some queries. When the nonchalantly saying the place is now vacant, one of the surrounding officers claims it as just the sort of place he was looking for and asks his captain permission to talk to the landlord privately.

Shed No Tears is bereft of any singular identity when contrasted against other thriller of the period. It is not a comedy but nor does it always dedicate itself to absolute seriousness. There are even moments when the viewer is invited to empathize with some of these pitiful souls, such as when Sam finally learns of Edna’s treachery. Poignantly enough, it is less the fact that she plans to keep the money for herself that pains him and more that she never loved him to begin with. The viewer may not care all that much for these people, although the film strives to make their escapade as entertaining as possible. To simplify the matter, the movie is just plain fun and sometimes that most basic of objectives can do wonders

-Edgar Chaput