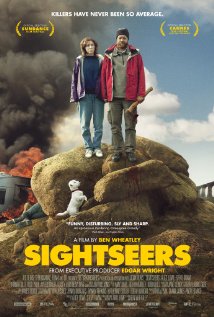

Directed by Ben Wheatley

Written by Alice Lowe, Steve Oram, and Amy Jump

United Kingdom, 2012

With grim determination, the new film Sightseers plays one blackly comic note on repeat for about 90 minutes. The film attempts to argue, in a slightly unique fashion, that maybe we all have a sociopathic nature tucked away in our genes just waiting to burst free and run rampant in our brains. Director Ben Wheatley, having become something of a cult figure thanks to his previous film Kill List, treats the tale of a thirtysomething couple traveling in a caravan through England with a straight face, just like the leads. The humor is—if you find there to be any—in watching the two protagonists float their way through an increasingly bloody vacation without batting an eye.

Steve Oram and Alice Lowe, who co-wrote the film with Amy Jump, play Chris and Tina, a couple who haven’t been together very long but have a strange, fierce, passionate bond that only grows deeper when he takes her on a caravan trip around the pastoral beauties of the United Kingdom. The little vagaries of vacation travel—the brutish vacationer who won’t pick up his trash and treats you like a jerk for pointing it out, the drunken bachelorettes, the tweedy exercise freak who’s particular about the cleanliness of his area—all serve as inspiration for these two to become vicious, thoughtless serial killers, lining their trail with gobs of blood without a care for who they leave behind to pick up the pieces.

The arresting visuals whenever Chris or Tina take out their anger, often rooted in their unsuccessful family and professional lives, rarely fail to be memorable, but the problem with Sightseers is also its calling card. Chris and Tina drive to a spot where they park their caravan, they meet a new group of people, this new group does something minor and realistic, yet aggravating enough to set the awkward lovers off, they kill someone, they move on. Lather, rinse, repeat for an hour and a half. Sightseers works well enough, but even once Chris and Tina begin to get bothered by each other, not just the close quarters, but the way they lie about their pasts as well as their future hopes, the movie feels repetitive. The ways in which Chris and Tina off their fellow travelers are inventive, at least; serial murderers or not, these two do not kill any two people the same way. But there’s not much else to latch onto in a constantly echoing narrative.

Oram and Lowe, best known for their work on British comedies like Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace, offer up enough intriguing details about the lead characters, at least in the first half. Tina has either reverted back to a childlike state or has always been fairly immature, and is guilt-ridden over the death of her mother’s beloved dog, Poppy, which happened a year ago. (And yes, for the dog lovers out there, the death does occur in a flashback, though we only see the nasty aftermath.) Chris fancies himself something of a novelist, and Tina his new muse, but only to keep up appearances, as opposed to doing any of the hard work. It should not come as a surprise that one of his victims is a published novelist, one who boasts of his past successes. If anything, this is also something of an issue with Sightseers, in that once the structure of the movie is pretty well established, as each new character is introduced, it’s hard not to wonder if they’re next on the chopping block.

Sightseers is well-made, and helps to further cement Ben Wheatley’s status as a solid new British director, next to other helmers like Joe Cornish and Edgar Wright, who was one of this film’s producers. And the concept is executed decently, methodically, and gruesomely. Perhaps the issue, thus, is that Sightseers doesn’t totally need to be a feature-length film, and would be far better served as a half-hour short. The notion that our fellow man is a bundle of neuroses that could spill forth into the world as unquenchable, unpredictable violence is not terribly mind-blowing, but the way Sightseers expounds on the notion is at least something different. Unfortunately, by the end of the movie, it’s closer to white noise than a grand revelation.

— Josh Spiegel