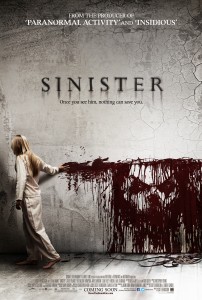

Directed by Scott Derrickson

Written by Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill

USA, 2012

Voyeurism is at the heart of most great horror films, a virus pervading protagonists like Norman Bates in Psycho or Mark Lewis in Peeping Tom. The basic idea of featuring characters who watch ghastly acts onscreen serves to mock, condemn, and unite the audience; we all love to watch, filmmakers argue. We may act horrified at grim, gruesome violence, but when we’re in the theater, scarfing down popcorn and guzzling an enormous soda, thrilling at blood and guts, it’s hard to act innocent. In the disturbing new film Sinister, Ethan Hawke plays a voyeur to the core, someone whose obsession with inexplicable and despicable Super 8 movies could lead to his undoing.

Hawke portrays Ellison Oswald, a true-crime author working on a new project about a grisly crime where a father, mother, and two children were hung to die in their backyard, leaving behind the third child, who’s now missing. The twist is, Ellison has deliberately moved his own wife and two children to the same house where those murders took place. As Ellison begins exploring his new digs, he finds a box of old home movies in the deserted attic that, to his surprise, feature footage of various families, including the previous residents, being killed violently; the only parallel is a freakish-looking specter who appears fleetingly in each film. Soon, creepy things start happening around the house, whether it’s a randomly appearing snake or Ellison’s son’s night terrors becoming worse and worse. Ellison is pushed to the brink, unable to choose whether he wants to let his avarice win out, writing a new bestseller to vault him into superstardom, or protect his family from this pagan terror.

Like some of the classic horror films, Sinister is a stripped-down, no-frills affair. For the majority of its 110-minute length, the movie never leaves the house where Ellison and his family now reside. It’s even more infrequent that Ellison ventures into the backyard or the front of the house. (Even when Ellison calls upon a professor of the occult, played by Vincent D’Onofrio, to give him details into the mysterious figure in those Super 8 movies, it’s over video chat.) And Hawke is in just about every frame of the film, presenting a nice, if disquieting, balance of morbid curiosity and genuine fear. Sinister works, almost sneakily, as a character study, as co-writers Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill (Derrickson also directed the film) quietly and slowly examine a man in mental freefall. Ellison abhors the life that comes without fame and glory, having had a taste of long-lasting success with a smash hit that briefly made him a literary celebrity a decade earlier. But he also very badly wants to be seen as a beacon of ethical fortitude, someone who’d never admit to being so personally covetous. Hawke captures this psychological struggle quite well. He’s a solid anchor for Sinister, a lead whose questionable integrity gives him enough shading to distinguish Ellison from other horror-movie character types.

However, because Sinister has such a narrow focus, it stumbles when trying to acknowledge the outside world. Ellison’s wife (Juliet Rylance, fine despite her character rarely moving beyond the nagging-wife role) refers a few times to being unable to enter the town without its denizens giving her a dirty look. The same goes for their son and daughter, who have trouble at school if only because the other kids know the opportunistic reasons why their father has moved them into town so suddenly. These are fascinating concepts to delve into, but we literally only see a handful of people who aren’t Oswald family members, three of whom are police officers. That Ellison, a noted author who specializes in digging up dirt on unsolved mysteries (or inaccurately solved ones), would be ostracized makes complete sense. However, Sinister isn’t committed to seeing that idea to a natural end point, or even a natural midpoint.

That said, Derrickson’s quite good at building tension in various sequences where Hawke is either piecing together or viewing the found footage, or skulking around his house, down the empty, unending hallways or venturing into the dark, spooky attic. Sinister, most of the time, avoids letting its soundtrack broadcast impending scares to the audience. While Derrickson and Cargill’s script does sometimes play around with horror-movie tropes like creaky doors or strange and frightening echoes, it builds enough of a foundation so that the story generates fear, not always relying on cheap, “Oh, it was just the cat!”- type jump scares.

Sinister subtly comments on the recent spate of found-footage horror movies like the Paranormal Activity franchise; however, it’s Ethan Hawke’s effective lead performance that carries the film, as with what his character represents. You could see Ellison Oswald as a self-loathing author, or as a criticism against voracious fame-hounds, or as an inward attack from the writers themselves. We can judge Ellison from our cushy stadium-seating chairs for being selfish, but we’re not so different from a character who can’t look away, who has to see how the horrific home movies at the center of Sinister climax. Sinister is strongest when analyzing just why we have to watch, and exactly how screwed up that makes us.

— Josh Spiegel