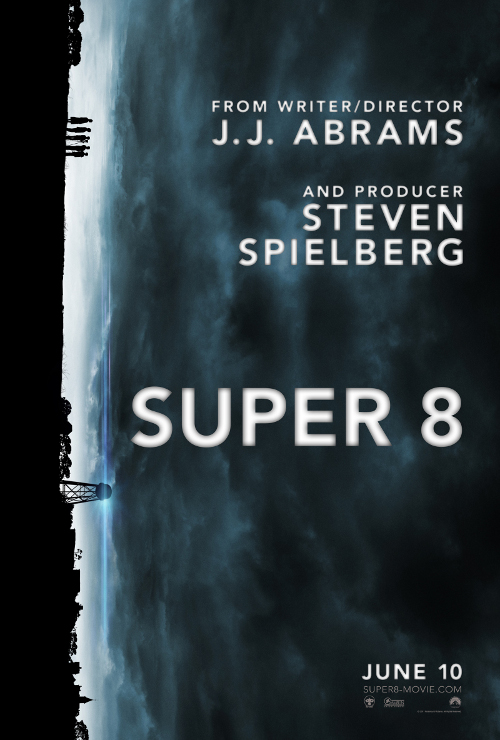

Written by J. J. Abrams

Directed by J.J. Abrams

USA, 2011

Depending on who you ask, Steven Spielberg is either Hollywood’s longest-running hack or its most dependable artist. On one point, however, his detractors and defenders must surely agree: Spielberg is, or at least was, an innovator. His run of blockbusters starting in the late 70s (E.T., Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the Indiana Jones movies, etc.) defined mainstream entertainment for a generation, fusing high-concept sci-fi/adventure narratives with a measure of universal human drama in a way that’s rarely been (successfully) matched since. J. J. Abrams’s third feature, Super 8, explicitly stakes a claim for itself as being akin to early Spielberg: not only does Spielberg produce the film, but for the first time in recent memory, the film opens with the original Amblin production logo.

Set appropriately enough in the summer of 1979, Super 8 stars Joel Courtney as Joe, a doe-eyed innocent whose mother perishes in an off-screen work accident as the movie opens. His stern-but-loving father, the town’s deputy sheriff (Kyle Chandler, who really has “stern-but-loving” down pat from his years on Friday Night Lights) wants to send him off to baseball camp and far away from his friends, who are making an amateur zombie movie under the dictatorial direction of Charles (Riley Griffiths). Naturally, though, Joel is less than thrilled, and defiantly accompanies his friends – along with the just-recruited Alice (Elle Fanning), who’s been added as a wife character in the name of “production values!” – to a train station at night to film a key scene. Naturally, disaster strikes, and the kids, along with the entirety of the town, turn out to be in grave danger.

Super 8 is most plainly the work of a filmmaker whose strength has so far been in renewal and retooling rather than imagination. While it might appear to be Abrams’s first original feature, Super 8 is so smitten with the movies it pays tribute to that it’s just as much part of an existing lineage as M:I3 or his Star Trek reboot. As a result, it divides its time between fresh, vibrant material that actually resonates and plot points that are a little too familiar. As befits a movie so beholden to other movies, Super 8 actually works best as a tribute to filmmaking itself: nearly all of the movie’s best scenes revolve around the making of The Case, the kids’ would-be contest winner. There’s even a moment of genuine power early on, when Alice turns out to be a cracker of an actress; in that moment, Abrams’s vision of filmmaking as a vehicle for self-discovery is most beautifully realized. (It helps that Fanning herself is, predictably, no slouch in the acting department.) That much of the barely-adolescent courtship between Joe and Alice’s revolves around his skills as a makeup artist is also a novel touch.

Super 8 is most plainly the work of a filmmaker whose strength has so far been in renewal and retooling rather than imagination. While it might appear to be Abrams’s first original feature, Super 8 is so smitten with the movies it pays tribute to that it’s just as much part of an existing lineage as M:I3 or his Star Trek reboot. As a result, it divides its time between fresh, vibrant material that actually resonates and plot points that are a little too familiar. As befits a movie so beholden to other movies, Super 8 actually works best as a tribute to filmmaking itself: nearly all of the movie’s best scenes revolve around the making of The Case, the kids’ would-be contest winner. There’s even a moment of genuine power early on, when Alice turns out to be a cracker of an actress; in that moment, Abrams’s vision of filmmaking as a vehicle for self-discovery is most beautifully realized. (It helps that Fanning herself is, predictably, no slouch in the acting department.) That much of the barely-adolescent courtship between Joe and Alice’s revolves around his skills as a makeup artist is also a novel touch.

Abrams makes a key choice, though, that substantially undercuts his material. Opening with the death of Joe’s mother feels abrupt; the film would really benefit from a more leisurely opening stretch wherein we really get to know the gaggle of kids who populate the film, as well as Joe’s dynamic with his father (or lack thereof). Opening with this traumatic event cheapens things somewhat, feeling like a shortcut to Spielberg’s oft-referenced “daddy issues” rather than something that meaningfully drives the movie. (This is only compounded later when Abrams adds an unnecessary plot wrinkle about the circumstances surrounding her death.) The other side-effect of this truncated opening is that the other kids – Griffiths, along with Gabriel Basso, Ryan Lee, and Zach Mills (aka “the lost Corey”) – wind up feeling more like types than characters, making it difficult to care about their fates, which is too bad, as they’re all likeable performers. (Especially when they’re making The Case.)

Of course, there’s also the half of Super 8 that Abrams has, typically, kept close to the chest. The answer to just what bursts forth from the train crash is a victim of the movie’s keen sense of anticipation: in other words, when you spend well over half your movie hiding something, it had better be spectacular when it finally emerges. That the answer lies, predictably, somewhere between Cloverfield and E.T., is a bit of a letdown, especially the tearful and fairly anticlimactic “showdown.” Still, it’s nice that Abrams didn’t skimp on the effects; it’s easy to believe that the clambering creature is really onscreen, particularly when Noah Emmerich’s trademark mug is nearby.

Of course, there’s also the half of Super 8 that Abrams has, typically, kept close to the chest. The answer to just what bursts forth from the train crash is a victim of the movie’s keen sense of anticipation: in other words, when you spend well over half your movie hiding something, it had better be spectacular when it finally emerges. That the answer lies, predictably, somewhere between Cloverfield and E.T., is a bit of a letdown, especially the tearful and fairly anticlimactic “showdown.” Still, it’s nice that Abrams didn’t skimp on the effects; it’s easy to believe that the clambering creature is really onscreen, particularly when Noah Emmerich’s trademark mug is nearby.

Ultimately, Super 8‘s effectiveness may depend on the viewer’s own sense of nostalgia. Moviegoers of a particular generation may be so charmed by Abrams’s devotion to the movies of their childhood and adolescence that they’re willing to overlook narrative shortcuts and the overly-familiar plot elements that crop up in the last reels. That in itself is a little unfortunate, because at its best, Super 8 threatens to become its own creature; as it is, it settles for being a flattering tribute.

Simon Howell