Taboo Tuesday is an exploration of some of the most outré sides of horror cinema.

Thoughtful, discriminating horror fans face a dilemma: We abhor the hypocrisy of a mainstream society that takes offense at fictionalized violence in a world full of the real thing while relishing the outsider freak cool that comes with being a horrorphile. In other words, we think the world would be a better place if everyone were more like us but, then again, much of the thrill would undoubtedly be lost if watching anything harder than The Walking Dead were to become a family affair.

News that “gorno” director Eli Roth was revisiting the cannibal film with The Green Inferno suggested this most disreputable subgenre was inching into the mainstream. Unthinkable. Subsequent headlines revealed that Inferno’s distributors had shelved it indefinitely. It seemed safe to assume this was due to last-minute timidity over graphic content and we might have believed order had been restored to the universe. This proved to be a business, rather than moral, issue however.

As of this writing, Roth’s redundant riff on the theme still hasn’t been given a release date. However much the horror community might hate to see a cannibal film in multiplexes (to say nothing of the sheer unoriginality of the concept), the uncompromisingly sleazy spirit of Roth’s flesh-eating forbears of the 1970s and ‘80s will live on.

Here, we celebrate a few of the best of the worst, inappropriate funk scores and all.

The old school

Jungle Holocaust (1977) and Eaten Alive (1980)

Directors Ruggero Deodato and Umberto Lenzi were the cannibal kings and their intense rivalry ultimately led to what are easily the two most notorious examples of the form (see below). Their competition began with these relatively low-key entries. Deodato’s Jungle Holocaust follows the survivors of a plane crash in the Malaysian jungle as they fall afoul of a previously undiscovered tribe of Stone Age cannibals. In Lenzi’s Eaten Alive, a young American and her guide walk willingly into the jungles of New Guinea in search of the lady’s missing sister. Each contains plenty of viscera munching, pungent sexual violence and animal cruelty; all of which would also feature heavily in both directors’ subsequent work. It’s all pretty distasteful, but the worst was still to come.

The “classics”

Cannibal Holocaust (1980) and Cannibal Ferox (1981)

Deodato and Lenzi both cranked up the volume on these. Deodato’s Holocaust has a somewhat better reputation amongst critics who admire the power of its found-footage conceit (two decades before The Blair Witch Project). While Ferox’s marketing included claims that it was “Banned in 31 countries,” (a claim at least one source couldn’t verify) Deodato actually found himself in an Italian court on murder charges in relation to the film. Ferox can’t boast that level of realism but, liberally recycling story elements from Eaten Alive, it offers a grueling cavalcade of depravity (very NSFW examples here). Both films certainly deserve credit for not painting the white interlopers as unambiguously noble victims and asking who the true savages are, but no right-minded person could take any real pleasure in either.

The outlier

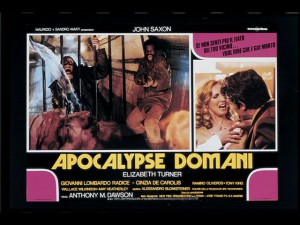

Cannibal Apocalypse (1980)

Director Antonio Margheriti’s filmography is full of low budget action features and his one foray into cannibal cinema could be a lost Cannon Films production. Which is also to say, Apocalypse is a good starting point for the neophyte. It does deliver at least one of the most memorable gore gags in the canon, but never feels as ugly as the preceding entries. It’s particularly notable that, with one arguable exception, the violence here never reaches the levels of misogyny that infect so many other of the films discussed (though there is some strongly implied statutory rape). Margheriti and co-writer Dardano Sacchetti also offer the intriguing concept of cannibalism as a virus forged in the barbarism of the war in Vietnam. In summation, the one least likely to make you hate yourself for watching.