Preface

When the pay-TV service Home Box Office debuted on a stormy night in the fall of 1972, its future hardly looked promising…or even assured. On the service’s opening night, HBO had less than 400 subscribers on a single cable system in Pennsylvania. They were treated to a hockey game and a two-year-old movie that had been a box office stiff. Due to technical difficulties caused by the storm, the opening night almost didn’t open at all, and nobody in the fledgling company even liked the name: Home Box Office.

Nor were there any particularly auspicatory signs of future success. By 1972, there was already a rather tall scrap heap of failed attempts at pay-TV dating back decades, and much of HBO’s own research confirmed the then oft-repeated adage that trying to get people to buy TV (after almost a quarter of a century of free broadcast programming) would be like trying to get people to buy air.

Flash forward forty-odd years and HBO is the largest pay-TV service in the world – that’s right, not just America, but the world, with a truly global subscribership of over 114 million here in the U.S., in Europe, Latin America, and the Pacific Rim; over $3 billion in annual sales; and a name – that same name even the company’s founders didn’t much care for – that’s one of the most recognized brands on the planet, right up there with Coca-Cola.

Between that rainy night in 1972 and today there have been a half-dozen predictions that the company had had its day, and, indeed, HBO has had its bad times, its missteps, its flat-out failures. And, certainly, it’s no longer as unique and novel as it was in its early years… as HBO pivots into HBO Max and joins the streaming revolution.

Yet…

HBO is still here, showing a remarkable resilience and ability to re-think itself and adapt to changing environments. And, it still produces some of the most acclaimed and provocative programming on the ever-expanding cable spectrum: shows like True Blood, Girls, and Game of Thrones.

But the most notable thing HBO did – and the thing that probably gets most overlooked – is that it changed…everything.

HBO has, in its four decades, become such an institution, it’s hard to remember what the entertainment landscape looked like pre-HBO. An entire generation has grown up with cable TV as the norm, and, if those kids were brought up in the areas where HBO first started, there’s a reasonable chance their parents grew up with HBO, too. Nineteen-seventy-two was a different world, and offered a media universe anybody under 30 might view as so monumentally different from today as to be alien. Nearly all of the changes that followed owe something – either directly or indirectly – to the success of HBO.

The service changed television, was largely responsible for the birth of the modern cable era, reconfigured the motion picture industry, and stoked an appetite for home entertainment and alternatives to Old Media pipelines sparking everything from home video to Internet TV.

Yet, despite numerous articles, references in other works, and even a collection of scholarly essays, there’s not a single public, published, full history of the company. The biggest thing to happen to television entertainment since the launching of the commercial broadcast era in the late 1940s has been remarkably undocumented.

It’s time to tell that story. Long past the time, actually.

HBO is worth the look for succeeding where so many others failed, for its ability to survive and remain relevant through its talent for reinvention, and for being such an integral factor in shaping what we watch and hear for entertainment, and how we watch and listen to it.

In the interest of full disclosure, I admit I’m biased. I worked there for 27 years. While HBO’s track record is hardly immaculate, I was impressed from my first day as an employee – and remain impressed even as an ex-employee – at the sheer tonnage of smarts contained in that cube of green glass on the corner of 42nd Street and Sixth Avenue in Manhattan. Even after being shown the door, I still think it’s a story not only worth telling, but one that deserves to be told.

In the coming weeks we’re going to take a journey and retrace how the world’s first and most successful subscription television service came to be, how it does what it does and why. Actually, we’re going to go back even further, before the beginning, because to appreciate the revolutionary quality HBO had in 1972, you have to understand what the service was rebelling against. HBO didn’t spontaneously combust in a vacuum; it was then the latest chapter in the history of a medium that had yet to discover its full potential. And to understand that, you have to understand how the status quo got to be the status quo.

Introduction

“Television is going to be the test of the modern world…we shall discover either a new and unbearable disturbance of the general peace or a saving radiance in the sky. We shall stand or fall by television — of that I am quite sure.”

E. B. White

Perhaps it began with a puff of smoke.

Some early brand of homo sapiens had something he wanted to say, and felt compelled to have a lot of his prehistoric colleagues hear it. So, he grabbed himself his mastodon pelt blanket in one hand, his sparking flints in the other, trudged up the nearest high hill, made himself a fire and started flapping the blanket making smoke signals visible for miles around.

And here, a few milennia later, are his somewhat better postured and less hairy kin still working from the same agenda. Instead of a blanket and flint, though, they have TV studios and uplink facilities. Instead of a high hill, they have transmission towers or — the highest “hill” there is — satellite transponders. Instead of smoke, they have electronic signals. Instead of a range of a few miles, they can reach entire continents simultaneously.

Then again, perhaps it didn’t start that way at all. Who knows? Cable television only arose less than 70 years ago and no one’s quite sure how, where, and by whom that started!

The point is that since members of humankind first began communicating with each other, they had been looking for ways to speak to larger and larger numbers of their kind at the same time either because of some compelling need to widely share their thoughts, or because it’s a more cost efficient way of selling soap. In either case, you can only shout so loud and then you have to start looking for a more far-reaching vehicle. Say smoke signals, or satellite transmission. Or Facebook.

There was a philosopher who said that when you look back over the course of your life, it looks like a smooth progression of events with one thing leading naturally to the next in a neat line that ends at the present, although when you were going through those same events they seemed chaotic, random, unplanned. The progression from our hairy little ancestor beating out a message in puffs of smoke to satellite transmissions that can blanket entire continents may similarly look connected by a series of gradual and logical steps. However, that smooth technological evolution only exists in retrospect. Backtracking from the advent of HBO, the pay service seems like an inevitability. It was anything but. Television technology — like any other technology — progressed in fits and starts, often through technological three-cushion bank shots, with developments that were often directed towards one goal but wound up somewhere else. The launch and eventual success of HBO was no different.

Back in the early 1800s, when the Baron Jons Berzelius isolated selenium, he didn’t do it because he had envisioned television as an end product. There was no great concerted plan to “discovering” television any more than there was a plan for what to do with it when it finally did find its way into being. With deceptive simplicity, radio and TV personality Gene Klavan succinctly put it this way in his book, Turn That Damned Thing Off: “…there never was a game plan for TV; it grew as it grew.”

However television started, and however it grew, it’s here. In fact, it’s everywhere.

Its images transcend the limitations of literacy and its signals respect no national or cultural barriers. Satellite carriage and portable receiving dishes make television reception possible anywhere on the surface of the earth; on any continent, any island, from pole to pole, and mobile uplinks mean that signals can be transmitted to a global audience from anywhere with equal ease. During the Gulf War of 1990, Saddam Hussein regularly tuned in to satellite transmissions of CNN to find out what was going on outside of Iraq. Michael Fuchs, one-time Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Home Box Office, believed views of a comparatively opulent West that East Europeans saw in bootleg videotapes and pirated satellite signals during Cold War days helped fuel their discontent with their lot under Communist regimes. TV knows no walls.

Up until the rise of the Internet, television was the dominant carriage of information from one place to another throughout the world for a good 40-50 years. More than film, radio, or the printed word, television had become, during the post-WW II era, the global population’s principal source of information and entertainment (and, for older demographics, it’s still a first choice over the Internet). It’s still the best way to reach a mass audience in one, fell swoop.

In the United States, a hardcover book can reach the best-seller list of the New York Times with sales measuring in the tens of thousands. A top rock album goes gold with sales of a hundred thousand. A motion picture hits the all-time box office hit list with ticket sales of over $200 million which translates into maybe 20-30 million ticket buyers — many of them repeat viewers — over a period of 1-4 months.

But, with at least one television set in 98% of all American homes (believe it or not, there are still people who either can’t afford a set, or — having decided TV is a brain-draining, soul-sapping, addictive, corrupting distraction and a fundamental evil — voluntarily elect not to have one), a Number One prime time television show will be viewed by 20-30 million or more families in the space of one evening!

Prior to an era of Wikileaks and YouTube-worthy faux pas, TV was usually the instrument that made — and just as often broke — political reputations, entertainment careers, fashion trends, sometimes through one season of a hit show, sometimes through televising a single event. In some judgments, Richard Nixon lost the presidential election to John Kennedy because young, vibrant JFK looked so damned good on TV during their 1960 televised debates…and sweaty, jowly Nixon and his persistent five o’clock shadow looked so damned bad. To others, Oliver North’s earnest appearance during the 1987 televised Iran/Contra hearings transformed him from lawbreaker into a patriotic hero.

For all its impact on society, television itself has never been immutable. If television has changed the kind of people we are, television itself has also been changed…and continues to change. The medium has evolved through the HBO-sparked ascendance of cable-carried television and along with it has evolved both the public and the industry’s concept of what television can and should do.

Somewhere around 95% of American homes are within reach of a cable hook-up, with, according to website Advanced Television, a little over 60% of homes actually subscribing (the Television Bureau of Advertising estimates another 30%, give or take, get pay TV through satellite subscription). Where the typical urban TV viewer might have previously received a half-dozen broadcast channels 30 years ago, the average — mind you, this is only the average — cable system offers over 100 channels carrying programming ranging from the latest Kardashian spin-off to live coverage of the U.S. House of Representatives.

In many ways, Home Box Office — which launched the modern cable era — has been a refutation of what had been the driving philosophy behind television since the late 1940s. It didn’t attempt to reach the largest audience, it didn’t try to please the largest numbers of people as much of the time as possible, and most critically, it asked people to pay for something they’d been getting for free. It was everything that television — so the mindset of its early years went — was not supposed to be. And in that, it created a niche audience programming template still followed today all across the cable spectrum.

Towards Felix the Cat

“Invention breeds invention.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson

When we climb into the family car we don’t think too much about it. We slip behind the wheel, turn the key, are happy it starts, and off we go. If we think about cars in a more expansive sense, it’s probably not all that expansive. When we start musing about how the old clunkers our parents used to drive evolved into the nifty little numbers with their sleek “airflow design” that we’re driving now, our musings probably don’t go very far. Our idea of automotive history may only extend back as far as Heavy Chevies from the ’50s, or maybe Model Ts from early in the century.

What we don’t think about are all those years and lines of unrelated research that eventually crossed and produced what we know of as a car. We don’t think of all the time, experiments, and theorizing that went into the development of the internal combustion engine (which eventually became the car’s power plant), or the development of vulcanized rubber (for the tires), petrochemicals (the plastic interior door handles), electronics (that mess of wire spaghetti inside the dashboard), wireless transmission technology (for the radio), refrigeration (for air conditioning), aerodynamic design (which is why so many cars these days all look alike), refractive lenses (for the headlight glass), or the experiments in electricity that produced the arc welder that’s used to do the spot welds that hold a car together. And let’s not even get into Global Positioning Systems and satellite radio and — … Well, you get the idea. What’s worth remembering here is that it’s a cinch that the fellow who dabbled with refractive lenses however many centuries ago (and it is centuries; Webster cites the year 1603 as the birth date of the word “refraction”) didn’t do his dabbling with automotive headlights in mind.

For every invention that we think of as having been sprung on mankind overnight, there lies behind it a long, little-known, meandering history of organized research, workshop puttering, and seemingly unrelated dabbling. Television’s no different.

Oh, there was a point at which the idea of television became clear in the minds of a number of tinkerers and inventors as something to aim at, but the components they would use to bring that idea to fruition had already been laying around for quite some time and many of them hadn’t been developed with the specific goal of TV in mind.

This is all by way of saying that if you’re looking for a birth date for TV, it gets a little hard. It depends on what you consider the beginning. It depends on what you consider TV.

It could just as well have begun with our Paleolithic friend from the Introduction, or it could have begun with another acquaintance from those pages, a Swedish chemist by the name of Baron Jons Berzelius.

The good baron isolated, for the first time in 1817, the element selenium. Because of its luminescent properties, selenium would later be used to create visual images in the early days of TV development, but at the time, all the baron was interested in was chemistry and physics.

Or, you could say things started rolling twelve years later when Michael Farady demonstrated what was, essentially, a primitive vacuum tube. Farady didn’t know it at the time, his main interest being simply to figure out how electricity worked, but the vacuum tube would be what made TVs and radios run before the transistor came along well into the next century.

Then there was Englishman Sir William Crookes who came along in 1878 with his development of something called the Crookes Tube. Crookes was another fellow interested in figuring out how electricity worked. He didn’t know that his work produced the first cathode-ray tube which is what served as a TV picture tube in the pre-flat screen era.

For those of you old enough to remember (or who might still have) a cathode TV screen, if you get your face right up to it, you can see the picture is made up of little pieces called “pixels”. The above gentlemen are just a handful of the pixels that compose the entire picture of the history of TV. The other pixels range from American inventor Philip Carey — who first used the “photoelectric effect” to transform pictures into various intensities of lights — to giants like Edison and Marconi, all of who laid down the early (and usually inadvertent) steps that led to television.

There was a point when the progression to television became inevitable because whether out of ambition, or sometimes simple curiosity (i.e. Berzelius, Faraday, et al), people are always looking for The Next Thing. When Samuel Morse invented the telegraph in 1835, it was the natural Next Thing to find a way of getting the human voice from one place to another by wire instead of just dit-dit-dit dah-dah-dah dit-dit-dit (Morse’s code for SOS). Alexander Graham Bell took care of that with the telephone. Once people started talking to each other over a distance, The Next Thing was, naturally enough, to get visual images from one end of the wire to the next.

Prior to 1884, fellows like Carey had managed some sort of visual transmission though one wouldn’t call it a picture, really. Carey and his fellow tinkerers could get a set of selenium photoelectric cells to transform a picture into various shades of light and then have that pattern repeated by another set of cells at the other end of the line, but it was hardly a representative picture.

If the successful transmission of an honest-to-God picture is what you’d consider TV’s birthday, then 1884 it is. Paul Nipkow was a German engineer who devised a way of transmitting a picture electrically for the first time with what he called his “mechanical scanning” system. This was not a moving picture, mind you, nor was it even a particularly good still Image in terms of quality, but it was a start.

Up until the 1920s, Nipkow’s scanning process was the basis for most television research. Then, along came a young Idahoan with the kind of name that usually gets you beaten up in school: Philo T. Farnsworth. Farnsworth was, besides being impressively bright, also incredibly precocious; he first laid out his idea for true electronic TV (no more mechanical scanning; it was TV like we know TV, more or less) on his high school chemistry class backboard in 1922. Within six years, young Farnsworth had created the first two-dimensional picture on his receiver.

Farnsworth gave TV researchers the key; now everyone interested in The Next Thing knew basically how TV worked. The next Next Thing was to make it work better.

By 1930, General Electric had shown off a prototype for the first home television receiver; Bell Telephone Laboratories had demonstrated a prototype for the first color television; the first variety show, first remote news report, and first TV drama had been aired by experimental TV stations; and a General Electric experimental station in Schenectady, New York had begun making regular broadcasts to the handful of equally experimental receivers being made available.

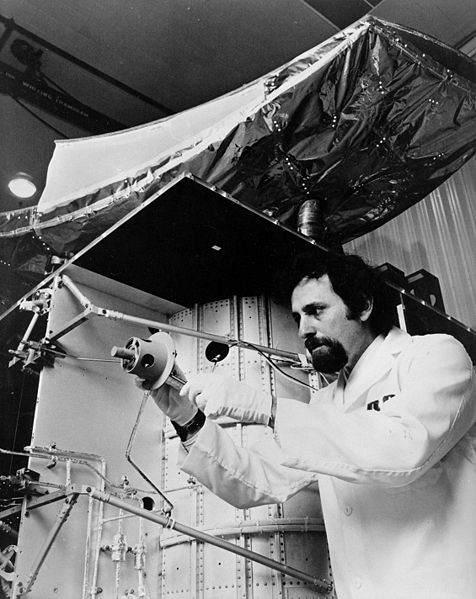

Of the significant developmental events which occurred during those eight years following young Farnsworth’s high school chalkboard doodling, a particularly significant significant event was the opening of an experimental television station in New York City. The year was 1928 and the first broadcasts of RCA’s W2XBS consisted of a small Felix the Cat (look him up, kids) statuette spinning round and round on a little turntable.

Granted, it wasn’t much of a show, but, then again, it wasn’t intended to be. Felix’s hours under the bright lights were to provide a subject for reception tests made by RCA (which was owned by GE) engineers in their very own homes scattered around the New York metropolitan area. Putting it more simply, the idea here was to answer the question: Is this gonna work?

The answer to that question was an obvious yes, but the technological demonstration of the practicality of broadcast TV was not what made Felix’s twirling notable. The importance here is tied to the fact that two years earlier RCA had formed the National Broadcasting Company for the purpose of distributing radio programming. The Felix broadcasts had now put NBC in the television business as well. The TV network was born; The Next Thing had arrived.

Baby Steps:

“We…repeatedly enlarge our instrumentalities without

improving our purpose.”

Will Durant

There’s no telling how much earlier commercial television would’ve been on the air if the early developmental days of the medium hadn’t had to suffer through two of the century’s more cataclysmic events, the first being The Great Depression.

TV technology development was the preserve of large corporations with large bank accounts. By this time, all the new gizmos required to make TV work simply cost too much for people like Philo Farnsworth to do the work in their backyard workshops. But, the Wall Street Crash of 1929 dried up enough of those corporate assets to slow the development of television (and nearly everything else in the world) considerably.

Slowed, but not stilled. Experimental stations still sprung up here and there, and broadcast technology inched its way along the road to improvement. Despite The Depression, by 1938 the DuMont home receiver was rolling off of assembly lines to become the first all-electronic TV set on the American market. Granted, there wasn’t a whole lot to watch with it, but TV had finally come to the American public. But, whatever momentum TV was building was stalled again, this time by something even bigger than The Crash: the Second World War.

TV didn’t exactly go into hiding for the duration. In fact, it was during the war years that commercial television was born. Although America had yet to get directly involved in the war, most of Europe had fallen to the Germans and the Japanese were fighting it out with the Chinese and British in the Pacific when, on July 1, 1941, the New York transmitters of NBC and CBS were licensed for commercial broadcasting. Half a year after Pearl Harbor, a third network, this one produced by DuMont, was also broadcasting out of New York.

Up until now, TV’s development bills had been entirely picked up by its developers. That started to change in 1942 when TV began to earn its keep. That was the year Bulova Watch bought itself a 15-second voiceover promotional spot on one of the nets; the first TV commercial.

The three networks produced approximately 30-40 hours of programming per week in those days although little of it resembled what we usually think of as typical television programming. The networks covered everything from opera to military maneuvers and political conventions, but few people cared. By then, the attention of the public — and the electronics and media industries — was on the war, and TV remained a gawky fledgeling with only 7,000 sets in use in the New York area, and even fewer in the small number of other cities with transmitters.

After the hardship years of the war, the post-war 1940’s were a prime time for a new form of entertainment and it did not take long for the new business to regain its momentum. Nineteen Forty-Eight saw the debut of yet another network: the American Broadcasting Company. By then, there were somewhere around 500,000 TV sets glowing in the night across the country. In the fall of 1951, NBC became the first network to establish coast-to-coast operations, feeding 61 stations around the country. By 1954, more than 26 million American homes were tuning in.

With NBC, CBS and ABC on the air (DuMont would fold its tents in 1955) and broadcasting across the country, the general outlines for commercial broadcasting as we know it today were in place. The three nets would sit at the top of the television heap virtually unchallenged for nearly a quarter of a century.

In the Beginning Was the Word — Radio:

“I like doing radio because it’s so intimate. The moment people hear your voice, you’re inside their heads, not only that, you’re in there laying eggs”.

Doug Coupland

We can watch TV — or movies, YouTube videos, play videogames, exchange video phone calls — from anywhere and everywhere: on line at McD’s, from our seat on our commuter bus or train (usually annoying the hell out of the napping business professional next to us), even from a toilet stall (crass, I grant, but I’ve seen — , well, ahem, I mean, I’ve heard it done). It’s nearly impossible for a generation growing up immersed, submerged, and buried in portable visual media to imagine the magnetic hold radio had on its audiences back in its early days. Think about it, all you smartphone and ipad users, wi-fiers and Hopper subscribers: there was a day when the peak of electronic home entertainment consisted of the family sitting together in the living room in the evening staring at a wooden cabinet whose sole visual attraction was a glowing dial (check out Woody Allen’s Radio Days [1987] to get some idea of the pop culture role radio had at its peak).

Emmy-winning writer/producer/director Bill Persky recalls for us what it was like growing up during the Golden Age of Radio:

The magic of radio, the miracle of radio, mostly because it was so amazing that such a thing could exist: this was at a time when everyone stopped to look up every time an airplane flew over. If you were lucky, there was one telephone in the house — or else you had to run down to the candy store when they sent someone up to tell you you had a call on their pay phone. Hard to believe it has all come so far and I have lived it.

The radio was like an electronic fireplace where the family gathered together to share the comfort of the after-dinner shows: “Fibber Magee and Molly” with its hall closet that used every sound effect known to man when it was opened, a moment you knew was coming but still delighted in anew; dramas like “Lux Radio Theater,” “Mr. First Nighter,” “Grand Central Station,” all featuring big Hollywood stars, right in your living room. It was a time when we expected less, and appreciated more.

Then there were the afternoon serials, fifteen minutes of adventure with “Terry and the Pirates”, “Captain Midnight,” “Buck Rogers,” “The Green Hornet,” and all the magical stuff you could send away for: decoder rings, belt buckles with secret compartments, silver bullets from the Lone Ranger, all for ten cents and a Silver Cup bread wrapper.

But mostly there was the part imagination got to play: it wasn’t all there in front of you, so you created your own pictures and that made it all more personal. We played those characters in our games, and since no one knew what they looked like, any one of them could be me.

Radio was personal.

Let’s see the Hopper top that.

* * * * *

Whether you talk about what the networks put on the air, how they did it, or even how the business end of their business worked, network television was, essentially — at least in its early years — just an extension of network radio.

RCA had created the first broadcast network — for radio — in 1926. This was a smart move for RCA since one of the things they built was radios. Creating a broadcast network gave people who bought their radios something to listen to, and having something to listen to gave people a reason to buy RCA’s radios. So, the National Broadcasting Company was formed ultimately producing two networks — the Red and the Blue — to distribute radio programming (NBC would later sell the Blue Network to Edward J. Noble in 1943 who used it as the foundation for ABC).

RCA had a competitor in the radio business; a phonograph and record manufacturer by the name of Columbia which was not about to allow RCA free sway over the new medium. Similarly to RCA, Columbia wanted a radio network to interest people in their products. A Columbia radio network would allow people to hear the music on Columbia records which gave them a reason to run out and buy those records along with Columbia phonographs on which to play them. Consequently, Columbia formed the Columbia Phonograph Broadcasting System which debuted in 1927 (the “Phonograph” part was soon dropped).

The radio business was supposed to cultivate a growing customer demand for radios and records and record players which meant revenue for RCA and Columbia. As for the nets themselves, their income came from advertising.

It worked like this. The nets would solicit a “sponsor” for each program they aired. Each sponsor would put up a certain amount of money in order to advertise its product during the show. In many ways, the show became the property of the sponsor.

Radio back then didn’t even remotely resemble what we get today, whether we’re subscribing to Sirius channels, using our IHeartRadio app, or trying to find a decent tune on our car set. Radio of the 1930s and ’40s was not only as popular as TV is today, but was programmed a lot like it as well. There was, naturally enough, recorded music, but there were also variety shows, game shows, news, talk shows, children’s programs, soap operas, cop shows, Westerns, dramas, and situation comedies (sitcoms).

Now if all of this looks a little familiar, it’s because television networks were launched by radio networks who lifted the TV network system directly from radio. As a matter of fact, the networks not only produced the same kinds of shows for TV that they’d produced for radio, they often took those very same shows from radio and put them on TV.

Sometimes the radio show went to TV in one piece, such as with The Jack Benny Show and Dragnet which made it to The Tube with their entire casts intact. Other times, as with Gunsmoke, certain “considerations” had to be made in the change in mediums such as having the muscular James Arness play Marshall Dillon instead of the radio program’s roly-poly William Conrad. All told, approximately 200 radio shows wound up making the trip to television (even Candid Camera — the great-great grandfather to shows like Punk’d — started out on radio as Candid Microphone!). In fact, a number of these programs survived as both radio and TV series for a period of time until the popularity of radio fell too low to justify keeping the radio version on the air.

One of the major reasons the DuMont network died was because it didn’t have a radio network. The TV nets’ radio counterparts helped pay the bills until their TV siblings could stand on their own legs (1949 was the last year of red ink for the TV nets; the following year they grossed over $90 million in ad revenue — close to $300 million in today’s dollars without accounting for changes in ad rates — and income would grow steadily into the 1980s), provided them with already in-place sponsors, talent and affiliate relationships, as well as a technological base. Not having a radio net also deprived DuMont of launching TV shows which had already developed solid audiences as radio programs. Lacking all these assets, having to start from scratch when the other nets had a head start going back to radio in the 1920s, DuMont could never catch up.

New York City became the hub of TV network broadcasting. Since the radio networks had been based out of New York, the new TV networks could easily piggy-back their transmission requirements onto the radio technology already in place. The New York locale also gave the networks access to the city’s stage community. Stage-trained performers — with their by-necessity strong vocal talents — suited the needs of live television better than the West Coast’s screen talents.

The sponsorship system made the trip to TV, too. With the present format of TV advertising, another hard-to-imagine task for us is picturing how close the tie between sponsor and program was in those days.

The cast of a show were, in practice, spokespersons for the product, and the show itself was as much a vehicle for product promotion as it was for entertainment (for those of you who bridle at the practice of “product placement”; gang, you don’t know what product placement was until you look at sponsored TV). In fact, some shows were actually created not by the networks, but by the advertising agencies representing a particular sponsor. Individual programs were identified with specific products i.e. Death Valley Days with “twenty mule team” Borax detergent, and The U.S. Steel Hour with — can you guess? — U.S. Steel.

This buddy-buddy arrangement proved a headache in the re-run market. By way of example, an enormous banner for De Soto cars (one of those cars you — and even your parents — are too young to remember, like the Nash and Studebaker) used to hang over the stage — and well within camera range — of Groucho Marx’s game show, You Bet Your Life. Years later, when the program was syndicated, the banner had to be optically cropped out of every program in deference to the new advertisers (as well as the fact that De Sotos had gone the way of the dodo).

The close arrangement between sponsor and program could also create headaches for the creative team behind a show. The sponsors held veto power over casting, the hiring of writers, directors, etc., and even over content. One of the apocryphal stories about the early days of TV concerns a drama about the Holocaust which featured Jews going to the Nazi gas chambers. According to the tale, the sponsor of the drama happened to be a gas company and objected to the use of gas chambers in the program and the writer was forced to change it to firing squads (you can see this story dramatized in Martin Ritt’s 1976 film about ’50s TV, The Front).

The power of the sponsor was such that it could even keep a show on the air that had a limited audience. In those days of McCarthyite paranoia, I Led Three Lives was the only TV series dedicated to the super-patriotic endeavor of exposing alleged Communist conspiracy and infiltration. Unable to find a network slot, the series lived only in syndication but was kept in re-runs well into the 1960s because the companies sponsoring the show — the kind of outfits that had the most to be paranoid about re: anti-capitalist thinking i.e. utility companies, banks, oil and steel companies — thought keeping it on the air was a “public service.”

This system of TV advertising eventually evolved into what we have today thanks to Sylvester “Pat” Weaver. Pat Weaver was the head of NBC in the late 1950s and he noticed that magazines made their money not by selling sponsorships, but by selling advertising space. From their example, Weaver got the idea of a network selling its own kind of advertising space and that’s pretty much what we have today.

The way it now works is that the advertiser rarely buys the time directly from the network at all. Ad agencies buy network time in bulk, then they sell the time as part of the advertising strategy they’re forming for their clients. Rather than sponsor an entire show, individual 60-second spots (this used to be the standard, but 30-second and 15-second spots are par now) are bought at strategic locations throughout the day and week.

Now this topic of TV advertising brings up the very interesting subject of ratings. You can’t discuss TV and not talk about ratings. Ratings deserve their own little discussion because they are to commercial television what air is to people. The same thing happens to a TV show that doesn’t get enough of a rating that happens to a person that doesn’t get enough air; it dies.

The Numbers Racket:

Do not put your faith in what statistics say

until you have carefully considered what they do not say.

William W. Watt

The nets don’t just pull a price out of their respective hats for their advertising time. Advertisers are paying for viewers’ attention. They want to know if they’re getting their money’s worth and the only way to do that is to know how many people are watching. This need has always been so imperative that as early as 1949, just one year after the third network — ABC — went on the air, and even before any of the nets had begun coast-to-coast operations, a regular ratings system was in effect.

Rating broadcast programs did not start with TV. Broadcast programmers had been doing that kind of thing back in the radio days for the same reasons: so that sponsors would know who was watching what, and whether or not those numbers justified the money the sponsor was laying out. A number of TV rating systems have come and gone over the years, but today (and for quite some time, actually), the be-all/end-all of national TV ratings are those supplied by the A.C. Nielsen Company. In the nine decades since “the Nielsens” were first used in radio (the company began measuring TV performance in 1950), they have come to be programmers’ bible of success and failure. While the equipment and methodology of the Nielsens has changed over the years and is often controversial — and continues to change and be controversial — the basic principal remains the same.

The Nielsen company uses a sample of several thousand homes to represent a particular “universe” (the universe is determined by what the client requires: all TVs in the U.S., just cable TVs, just cable subscribers with premium subscription services, etc. To represent the general national audience Nielsen uses a sample of 4,500 homes). The viewing patterns of this universe are measured to determine a “rating” (how many TVs of all the TVs in the specific universe are turned to a particular show) and “share” (how many TVs of just those sets that are actually turned on are tuned to a particular show). Nielsen uses a formula involving the rating, the number of houses using television, or HUT, and the share to establish a particular show’s Nielsen standing and what an appropriate cost for a commercial spot put on the air at a particular time should be. When Nielsen looks at the cost of commercial spots, they talk about the cost per thousand, or cpms for a spot. In English, that means the advertiser’s cost for every thousand viewers watching that show.

Much of the controversy over the ratings has to do with their accuracy, and, more pointedly, exactly what the ratings measure. A Nielsen meter attached to a television set will record that the set was tuned to a particular station at a particular time, but it won’t measure whether or not anybody was actually in the room watching it (there are people who just like the sound of the TV on to keep them company), or whether or not they enjoyed what they were watching (as in, “I would’ve watched something else but everything else sucked even worse!”), and so on.

Over the years, Nielsen, along with the research departments of advertising agencies, networks, and production companies — to name just a few — have tinkered with replacement or additional technologies, but to date nobody’s come up with anything they’re completely happy with.

Back in the late 1980s, one of HBO’s senior scheduling execs once shared with me the problems with viewing measurement systems:

We started out just using meters but we wanted to know if people were actually enjoying what they were watching and how much. The meters couldn’t tell us that so we added diaries. Each metered home also got a little diary, and they were supposed to mark off what stations they were watching and when, and then there was a place to mark how much they liked what they were seeing: very much, moderately, not very much, not at all, and so on.

The problem is the families lied when they filled out the diaries. After the first few days of the month, they would get lazy and stop filling out the diary as they went along. Then, at the end of the month, when they were supposed to turn them in, one member of the household — usually the lady of the house — would fill out the diary from memory.

Well, it wasn’t so much memory, as her filling out the diary with what she wished her family’d been watching instead of what they actually watched. For instance, we’d get back a lot of diaries and there was all this PBS programming written in, but when the meter results came back, PBS ran at a near-zero. According to the diaries, no one in the house ever watched any of our Cinemax late-night adult programming, but then the meter readings came back and it turns out that was the most-watched stuff in the house.

We finally quit using the diaries.

“Ratings,” says respected TV producer Gerald Abrams, “are like dipping a dip stick in the ocean. It’s a small sampling, but so far it’s the best they can do.”

Some of the problems programmers have with ratings may have less to do with how accurate the ratings are then with how good they make a programmer look. In the 1980s, when the networks began to steadily lose audience to cable, the nets began complaining that the Nielsen samplings were slanted towards cable homes. Their point was that Nielsen’s 4,500 homes representing the national market contained a higher percentage of cable homes than the percentage nationally. That, they said, gave the nets an artificially lower rating then they should’ve gotten with a sample they considered more fairly representative.

On the other hand, the nets have their own way of artificially inflating ratings during their “sweeps.” During one week in November and another in February, the nets use the ratings from those weeks to set the standard for advertising rates for the season. But what normally happens during a sweeps week is that instead of measuring a typical week of programming, the nets load the week’s schedule with programming “stunts.” Typical stunting includes running one-time specials, pre-empting a normal night’s schedule to run back-to-back episodes of a top-rated series, airing a top-of-the-line sporting event, and so on.

One curious aspect of ratings is that they rarely have absolute value. When everybody in America tunes into one show, that’s going to be a great rating no matter how you interpret it. But, most programs don’t have that kind of unquestionable standing.

On nights when fewer people watch TV, a show can have a low rating but a high share (in English: a big hunk of a small pie) and be the Number One program of its night. On another night, one where more people are watching TV, the rating of a particular program might be higher but the share lower (a small hunk of a bigger pie). In other words, the same show that pistol-whipped Last Resort on one night can get steamrollered by Big Bang Theory on another night, even if holds the same rating because its share keeps changing. That’s why it’s just as important to schedule a show with as much consideration as it’s produced. More than one good series has been killed by putting it on a bad night at a bad time.

Obviously, ratings are very useful. They tell a network where its strengths and weaknesses are, and it does the same for people buying ad time; vital information when you’re talking about the big bucks that go into TV advertising. The cost of commercial spots can vary enormously depending on the time of day and a given show’s standing in the ratings, but even at the low end, we’re talking significant money. Prime time advertising rates average in the $120-140,000 range for a 30-second spot, but they can range — depending on the show — from low five figures to high six figures. Special events can run the cost of a spot into the rarified atmosphere of millions, with a single 30-second spot during last year’s Super Bowl costing a wallet-killing $2.4 million. All told, the broadcast nets are looking at a whopping $9 billion worth of buys for the upcoming season.

Since the nets’ business is mainly to deliver eyeballs to advertisers, if a show can’t deliver them — at least enough of them to justify the cost of the show — then that show is history. Even if it’s the best thing to show up on the tube since Felix the Cat.

At the end of each season, the networks take a fair bit of flak for cancelling good shows, but, to be fair, the nets have bills to pay. A typical one-hour network drama costs $2-5 million per episode to produce, with a season needing 22-24 episodes. That means, even at the low end, you’re looking at a tab for the season of $44 million — and that’s for a single show. A network needs something in the neighborhood of 21 hours of programming just to fill out its weekly prime time schedule. That makes for big bills!

And while the cost of making things like cars and personal computers usually goes down over time, the cost of making a series paradoxically goes up the longer it runs, at least the above the line costs do (above the line costs would be the talent costs; salaries of the stars. Below the line costs would be the actual cost of production; construction of sets, cost of studio time, etc.). If a show becomes popular, the above the line cost of stars on the show usually rises when it comes time to re-negotiate their contracts. If a performer assumes that they are important to the success of the show, they feel they have enough negotiating leverage to get their salary bumped higher. Some series have been cancelled after several years not because the ratings have fallen so much as it was no longer financially practical to keep the show on the air.

That fiscal burden falls mainly on the producer of the program; not the network. The nets negotiate per-episode fees with producers, but production costs have risen over the years (star salaries aside), and the nets, having lost a large hunk of their audience to cable, have become tighter with their money.

Most network TV programming is now “deficit financed,” which means that the shows cost so much to produce the network fee only partially covers a producer’s costs. Most producers don’t profit on a series until it goes into syndication when re-runs of a series are sold to cable and/or individual TV stations around the country. However, to successfully syndicate a program requires the producer to have enough episodes on hand so that local station and cable network program directors can “strip” the show, meaning they can run at least one episode on at least every weeknight. The rule of thumb is that a producer needs at least three seasons of a one-hour show, or five seasons of a half-hour show on hand to successfully syndicate it (although cable’s bottomless appetite for programming and niche audiences for cult favorites have provided surprisingly successful syndication opportunities for network flops like Firefly, even though the series only ran 14 episodes).

You can see why so many people are so concerned about ratings.

Even the nets would agree, though, that a sad side-effect of the ratings business is that a number of good series’ over the years have been cancelled because the millions of people who watched a particular show represented a number that was millions too low. Real life French Connection cop turned TV producer Sonny Grosso, with over 900 hours of programming under his belt, considers the numbers game and the acclaimed shows that have fallen victim to it, and says, “I’d rather be lucky than good.”

The other rather unappetizing side-effect, in the eyes of many TV critics, has been a network tendency to explore programming whose major value is the number of viewers it can attract rather than its quality as entertainment. The phrase often used to describe this practice is, “appealing to the lowest common denominator,” which is TV programming’s version of throwing chum in the water to draw sharks.

This is hardly a recent trend in network television. It goes back to Day One, something Newton H. Minow recognized when he assumed chairmanship of the Federal Communications Commission back in 1961. Minow, reflecting on where television had gotten itself in just little more than a decade, made a now famous speech to the National Association of Broadcasters in which he said:

When television is good, nothing…is better. But when television is bad, nothing is worse….sit down in front of your television set when your station goes on the air and…keep your eyes glued to that set until the station signs off. I can assure you that you will observe a vast wasteland. You will see a procession of game shows, violence, audience participation shows, formula comedies about totally unbelievable families, blood and thunder, mayhem, violence, sadism, murder, western badmen, western good men, private eyes, gangsters, more violence, and cartoons. And endlessly, commercials — many screaming, cajoling, and offending…

There hasn’t been a TV season since where every TV critic in the country, at least once, hasn’t felt obligated to quote Mr. Minow’s speech.

The Wasteland

Television is a gold goose that lays scrambled eggs;

and it is futile and probably fatal to beat it for not laying caviar.

Lee Loevinger

When people argue over the quality of television programming, both sides — it’s addictive crap v. underappreciated populist art — seem to forget one of the essentials about commercial TV. By definition, it is not a public service. It is not commercial TV’s job to enlighten, inform, educate, elevate, inspire, or offer insight. Frankly, it’s not even commercial TV’s job to entertain. Bottom line: its purpose is simply to deliver as many sets of eyes to advertisers as possible. As it happens, it tends to do this by offering various forms of entertainment, and occasionally by offering content that does enlighten, inform, etc., but a cynic would make the point that if TV could do the same job televising fish aimlessly swimming around an aquarium, it would (actually, there was something close — the old DuMont network poked a camera out a window overlooking New York City’s Madison Avenue while an off-screen voice recited poetry over the pictures, and called it Window On the World).

This isn’t because the people who run TV networks are cheap or crass (whether they are or not, well, that’s another argument). In fact, over the history of the medium, there have been network chiefs — like William Paley who headed CBS from its inception into the 1980s, and NBC chieftain in the 1980s Grant Tinker — who felt obligated to make their networks earn their money by offering as much high quality programming as they felt their networks could afford and their audiences could digest. For many years — decades, actually — quality programming was so much a part of the CBS reputation that the network was often referred to as, “the Tiffany network.” But, whether a network boss was — or is — a pure mercenary or a starry-eyed idealist about programming, all network honchos were — and still are — in the same boat.

Because TV networks broadcast over the public airwaves, the FCC keeps telling them that they have a certain amount of responsibility to the public, but be that as it may, these are still companies just like General Motors and IBM: they’re in business to make money. When they don’t make money, the stockholders and investors and board members get mad and dump the old management and then hire new managers who say they’ll make sure the company makes money, and if they don’t, they get dumped.

Commercial television has always operated on a very simple cause-and-effect principal: what makes money is putting on shows that people watch. To make a lot of money, you put on shows a lot of people will watch. Good, bad, or indifferent, and despite the legitimate squawking of TV critics and FCC guardians like Newton Minow, a lot of what has filled the network airwaves is there not solely because some tasteless network programmer put it on, but because that’s what people watched. In bulk. And often with a certain amount of enthusiasm (Whaddaya think of that, Newt?).

In the early days of commercial television, TV was something of an elitist medium — although producer Gerald Abrams might argue with the word “elitist”: “You have to remember that in the 50s, most people in American didn’t even have TV! I’m not saying it was elitist to own one, but having a TV was not a given then the way it is now.”

And understandably so, considering how much money it cost to buy one. In the late 1940s, a set could go for $150.00 or so which, figuring for inflation, would be the modern-day equivalent of somewhere around $1000 today. That In mind, it’s no surprise that in 1948, the year people usually consider the start of the modern broadcast era, there were only 500,000 sets in use in the entire United States, and by 1950, the total was still less than four million — only about 9% of American homes — with most of those sets located in major urban areas. Early programmers found themselves looking at an audience that was primarily upscale, urban, well-educated. That explains a lot of the top-end programming from those years. Josh Sapan, CEO and President of AMC Networks, characterizes the era as a “…sort of early adolescence (with) a lot of experimentation.” The hallmarks of TV’s first decade were, “Great drama, quiz shows, and shows (adapted) from the radio.”

The “great drama” included the best remembered programming cornerstone of the early 1950s; the drama anthologies like The U.S. Steel Hour, Philco Playhouse, Playhouse 90, and a host of others, many of which were telecast live. These intelligent, literate stories became dramatic benchmarks that TV critics still use to measure the rise and fall of program quality.

Even when programming began to diversify into more generally popular forms, like Westerns and game shows, programmers still had an eye on that upscale urban audience. A series like Gunsmoke packed in enough character-driven drama to be commended for its adult stories, while including enough galloping horses, punch-outs and shoot-’em-ups to keep almost everybody not interested in high drama happy.

Perhaps the measure of the kind of program quality on the nets in those days is the high caliber talents who came out of TV to go on to bigger things. There were directors like John Frankenheimer (who went on to make, among other feature films, The Manchurian Candidate [1962], The Birdman of Alcatraz [1962]), Franklin J. Schaffner (Patton [1970], Planet of the Apes [1968]), Sam Peckinpah (Ride the High Country [1962], The Wild Bunch [1969]), Blake Edwards (the Pink Panther movies), George Roy Hill (Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid [1969], The Sting [1972]), Ralph Nelson (Lilies of the Field [1963]), Arthur Penn (Bonnie and Clyde [1967], Little Big Man [1970]), and Sidney Lumet (Serpico [1973], Dog Day Afternoon [1975]).

Performers who paid some of their early dues on TV included Paul Newman, Rod Steiger, Dustin Hoffman, Shirley Knight, Cliff Robertson, Jack Lemmon, George Peppard, Charles Bronson, John Cassavetes, Tuesday Weld, Jack Palance, Sally Kellerman, Robert Redford, Martin Sheen, Warren Beatty, Robert Duvall, Nancy Marchand, Lee Marvin, James Coburn, Dennis Hopper, Steve McQueen, and Clint Eastwood.

And there were the writers: Rod Serling (Seven Days in May [1964], Planet of the Apes), Sterling Silliphant (In the Heat of the Night [1967]), Paddy Chayefsky (Altered States [1980], Network [1975]).

It is perhaps another measure of the strength of some of these writers that their most notable TV work was considered worth amplifying and turning into material for the big screen. Making the trip from small to big screen were, among others, Serling’s Requiem For a Heavyweight (1962), Reginald Rose’s 12 Angry Men (1957), J. P. Miller’s The Days of Wine and Roses (1962), Tom Gries’ Will Penny (1968, based on his TV script, “Line Camp” for the series The Westerner), and Chayefsky’s Marty, the big screen version of which won the 1955 Oscar for Best Picture.

In 1950, there were almost a dozen thirty- and sixty-minute anthologies on the air, each presenting a play a week. Two were among the Top Ten series of the year. But, despite critical applause and their reputation as the cream of television, anthologies’ rankings went down as the number of TVs sold went up. By 1955, two out of three households had a TV set and anthologies had forever dropped out of the Top Ten. By 1960, when almost everybody had a TV, only three were still on the air.

Sponsors wanted programming that provided them with the widest possible audience for their advertising messages. Network programmers worked to deliver it to them. The increasing complaint among observers was that, as a result, TV programming became increasingly homogenized and escapist. In other words (or rather, in a word): blah. The 1950s were a time when the seasonal Top Twenty shows regularly included the sitcom, a format that would be the backbone of TV programming seemingly forever. In the ’50s such top-rated programs included I Love Lucy, December Bride, Father Knows Best, The Danny Thomas Show, The Life of Riley, Our Miss Brooks, and The Gale Storm Show. Whatever their relative merits, and some were better than others, these were hardly shows that plugged into the complexities and problems of what we like to refer to as, “The Real World.”

In the hunt for programming that worked, TV producers became notoriously imitative. Ernie Kovacks, a noted TV comedian of the day, put it this way: “There’s a standard formula for success in the entertainment medium, and that is: Beat it to death if it succeeds.”

Take what happened with Warner Brothers for example. Like all of the big movie studios, Warners had been seriously hurt by television. At the end of World War II, 80 million people were going to the movies every week. By 1960, only 43.5 million were still going to the movies weekly, and the number was still heading south. So, to compensate, Warners decided to get into TV production. They sold off their pre-1948 film library to finance the venture and by the time they hit their ’50s TV production peak, they were supplying one-third of prime time programming. The relevant point here is how much alike some of these Warners shows wound up looking.

There was 77 Sunset Strip (hip young private eyes working in L.A.), Surfside 6 (hip young private eyes working out of Miami Beach), Hawiian Eye (hip young private eyes working out of Honolulu), Bourbon Street Beat (hip young private eyes in New Orleans), and The Roaring Twenties (hip young investigative reporters working out of New York City in the ’20s). If they all sound a little similar, trust me as someone who grew up watching them: they were! And not just a little.

Not that there weren’t exceptions. The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis was pretty hip for its time in its look at high school teens. The series was noted for its touch of glib sophistication in the humor, a certain surreal quality to the hapless Dobie punctuating each episode by speaking directly to the audience in the shadow of Rodin’s “The Thinker” statue, and a “relevant” edge in that Dobie was the product of very working class parents instead of the picture-perfect suburbanites of Father Knows Best or Ozzie and Harriet (where, despite living in a very nice house in a very nice part of a very nice town, the family had no visible means of support — Ozzie seemed to hang around the house in his sweater all day every day). There was also the classic The Honeymooners which presented a tenement couple living in a barren walk-up with few prospects for improvement. They squabbled, fought, yelled, dreamed and failed; very much against the grain of where most 1950s series TV was going.

Producer Gerry Abrams remembers the bad and the good: “TV was all black and white in the ’50s, so besides just watching test patterns (I kid you not), people watched roller derbies (the women were the best!), and wrestling with stars such as Argentina Rocca and Gorgeous George (but also) a brand new show from NBC called The Today Show. You also had Your Show of Shows starring Sid Caesar with writers like Neil Simon, Woody Allen, Larry Gelbart, Mel Brooks, and Carl Reiner. Not bad, huh?”

Josh Sapan remembers another bit of late ’50s/early ’60s gold, one that still holds up rather spectacularly over a half-century later: “The one that stands out for me, head and shoulders above the others, is The Twilight Zone. The Rod Serling intro, which should have comforted kids by acknowledging that (the show) was made up, made (its) possibility seem more real. The characters and story were dominant v. the sci fi (elements), and the pace, casting, and directing were so different (from other shows of the time). He (Serling) was an early TV auteur, and, I think, the full package.”

Still, for the most part, America on television was suburban, comfortably middle class, and socially untroubled. Oh, and it was also generally, invariably, ideally white.

African Americans rarely appeared on early TV. Amos and Andy, adapted from the radio series, featured a nearly all-black cast but was soon cancelled in controversy over the depictions of its black characters. Blacks and whites enjoyed listening to Nat King Cole’s records, but his 1956-57 variety show was cancelled after a year of being unable to attract viewers or sponsors. Beulah was a reasonably popular series but hardly heralded equality among the races with its African American lead a maid for a white family.

Black Americans on TV were so singular, that the most singular thing about the blacks that appeared on two of producer Nat Hiken’s series’ — The Phil Silvers Show and Car 54 — was how unsingular they were presented. The parts were on par with those of most of the white supporting players and no big deal was made of their presence; they were simply “one of the guys.” Wow. Imagine that.

Emmy-winning writer/producer/director Bill Persky gives some idea of how sensitive networks could be over the most innocuous inclusion of race. In the early ’60s, Persky joined the writing stable of the hit sitcom, The Dick Van Dyke Show. According to Persky, a 1963 episode — “That’s My Boy” — sent CBS execs into conniptions. In the episode, Rob Petrie (Van Dyke) is convinced that after his wife, Laura (Mary Tyler Moore), has had a baby, the hospital gave them the wrong baby to bring home. Rob calls up the other father, has him come over to his house to confront him with his suspicions. Door bell rings, Rob opens the door and standing there is black actor Greg Morris.

“In 1963, the racial situation in the country was starting to boil over,” Persky remembers, “and making it a source of comedy was unheard of.” According to Persky, It was only series creator/producer Carl Reiner’s threat to take the story of CBS’ objecting to the episode to the press that pushed the net to cave.

“The reaction to (the episode) was amazing, and the show became a classic because it, in a small way, broke the fever that was burning up the country.”

Generally, what TV fed throughout its adolescence was a sense of peace, prosperity, and comforting uniformity which was as distorted a view of The Real World as you could have while sober. This was, after all, the decade of the Korean War, Joe McCarthy’s anti-Communist “witch hunts,” court-ordered desegregation, the revolution in Cuba, and the Kefauver hearings on organized crime.

The peaceful surface of TV-America was broken only on rare occasions. TV and radio journalist Ed Murrow tackled the McCarthy issue twice on his See It Now documentary series, and both the McCarthy/Army hearings and the Kefauver hearings were covered by television. Still, their overall impact on TV content was nil. Father continued to know best, the sheriff always got his man, and love won out in the end. The Real World received only cursory coverage on the evening news which was then only a 15-minute broadcast.

It remained for other mediums to grapple with the big issues of the day. Tennessee Williams took on America’s passions and mental foibles, and Arthur Miller exposed the failings of the American Dream on stage. On the movie screen, Pork Chop Hill (1959) was one of a number of grim films about Korea, while Edge of the City (1957) tackled racism, On the Waterfront (1954) exposed corruption in the labor unions, The Man With the Golden Arm (1955) frankly depicted narcotics addiction, and the explosion of film noir thrillers like Kiss Me Deadly (1955) reveled in post-World War II disillusionment and paranoia.

What people wanted in their living rooms was reassurance and TV gave it to them. If sponsors and programmers were pumping out the pap, well, nobody was making the millions watch. In fact, if the ratings are any judge, all those shows Newton Minow was dissing were being watched quite avidly.

Consider these Top Five lists from the 1950s:

1950-51 season:

1. Texaco Star Theater (variety)

2. Fireside Theatre (drama anthology)

3. Philco TV Playhouse (drama anthology)

4. Your Show of Shows (variety)

5. The Colgate Comedy Hour (variety)

1951-52:

1. Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts (variety)

2. Texaco Star Theater

3. I Love Lucy (sitcom)

4. The Red Skelton Show (variety)

5. The Colgate Comedy Hour

1952-53:

1. I Love Lucy

2. Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts

3. Arthur Godfrey and His Friends (variety — old Arthur was the only guy to have two top shows on the nets at the same time!)

4. Dragnet (police drama)

5. Texaco Star Theater

1953-54:

1. I Love Lucy

2. Dragnet

3. Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts

4. You Bet Your Life (game show)

5. The Milton Berle Show (this used to be Texaco Star Theater)

1954-55:

1. I Love Lucy

2. The Jackie Gleason Show (variety)

3. Dragnet

4. You Bet Your Life

5. The Toast of the Town (variety)

1955-56:

1. The $64,000 Question (game show)

2. I Love Lucy

3. The Ed Sullivan Show (this used to be

The Toast of the Town)

4. Disneyland (family anthology)

5. The Jack Benny Show (sitcom)

1956-57:

1. I Love Lucy

2. The Ed Sullivan Show

3. General Electric Theater (drama anthology)

4. The $64,000 Question

5. December Bride (sitcom)

1957-58:

1. Gunsmoke (Western)

2. The Danny Thomas Show (sitcom)

3. Tales of Wells Fargo (Western)

4. Have Gun Will Travel (Western)

5. I’ve Got a Secret (game show)

1958-59:

1. Gunsmoke

2. Wagon Train (Western)

3. Have Gun Will Travel

4. The Rifleman (Western)

5. The Danny Thomas Show

1959-60:

1. Gunsmoke

2. Wagon Train

3. Have Gun Will Travel

4. The Danny Thomas Show

5. The Red Skelton Show

Maybe it was precisely all those complexities of the real world that made people relish simplistic solutions, sparking an explosion of cops, private eyes, and cowboys on TV in the late 1950s and into the 1960s. Dragnet, M Squad, Racket Squad, Highway Patrol, Have Gun Will Travel, Cheyenne, Gunsmoke, Yancy Derringer, Bonanza, and more, all depicted simply-defined problems quickly resolved, more often than not, with a well-placed gunshot or right hook. The simple life of the saddle tramp seemed especially endearing at one point; in 1958, there were 30 Westerns stampeding across the tube, and twelve were in the Top Twenty.

The critics moaned about the monotony of it all. Comedians made jokes about how you couldn’t change channels without finding horses and saloons. Were audiences watching simply because there was nothing else on?

In a 1963 study on audience attitudes conducted by Gary Steiner, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Chicago, when asked, “What are some of your favorite programs — those you watch regularly or whenever you get a chance?,” the top choice from twelve categories was, “Action — Westerns, crime, adventure.” “Comedy/Variety” was just a few percentage points behind. “Regular news” was a distant sixth, “Heavy drama” a more distant eighth. When asked to respond with more general categories — “Light entertainment,” “Heavy entertainment,” “News,” “Information & public affairs,” and “All others,” 82% ticked off “Light entertainment” as their first choice for viewing.

Ed Murrow’s acclaimed documentary series, See It Now lasted three years in prime time, but his celebrity interview series Person to Person (a predecessor and weekly version of Barbara Walter’s celeb chats) ran for eight years. See It Now got bumped from prime time in 1955 in favor of far more popular The $64,000 Question. That says something about audience tastes right there.

Quiz and game shows fed the same sort of desire for good feelings and an American ideal. In the late 1950s, they fueled the dream of easy prosperity, offering a short cut of prize money to take a lucky few to the comfortable suburbs where Ozzie lived with Harriet. A game show held a place in the Top Ten every year of the 1950s. In 1955, there were three game shows in the Top Ten, with The $64,000 Question being the most popular show on all of TV for the season. Quiz shows were so big with audiences at the time, that the producers of some of them rigged the competitions so they’d be sure that the contestants most popular with the public won.

The social and international problems of the 1950s paled next to the comparatively cataclysmic upheavals of the 1960s. The decade began with the Bay of Pigs fiasco, the Cuban missile crisis, a heated nuclear arms race, and went on to the tragedies of the Kennedy assassinations, Vietnam, the murder of Martin Luther King. There were college takeovers by students, urban riots, violent pro- and anti-war demonstrations, Women’s Lib, Black Power, the Stonewall riots, and the “police riot” in Chicago during the 1968 Democratic convention.

Discontent, despair, and cynicism kicked off a streak of disturbing big screen movies throughout the decade including the likes of Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), The Manchurian Candidate, Fail Safe (1964), Bonnie and Clyde, In the Heat of the Night, The Sand Pebbles (1966), Point Blank (1967), Dirty Harry (1971), The Wild Bunch, and Midnight Cowboy (1969). Along with their darkening attitude, the movies had also acquired more graphic violence, sex, and “adult” language.

And on television?

In the era of disillusionment with Vietnam, war was still defined on TV in traditional, heroic World War II terms through series’ like Twelve O’Clock High, Gallant Men, and the long-running Combat. If family and societal values were being fought over — literally — in the streets, the families on The Beverly Hillbillies, Mr. Ed, and The Donna Reed Show all seemed to be getting along fine. And there were still all those gosh-darned cowboys: Wagon Train, Gunsmoke, Rawhide, The Virginian, The Big Valley, The High Chaparral, and the unending Bonanza.

Those shows that did try to bring an honest, gritty edge to the airwaves were usually met with critical kudos and a short life. East Side, West Side, featuring George C. Scott as a New York City social worker, lasted one season; Slattery’s People was a political drama featuring Richard Crenna as the minority leader in an unnamed state legislature which lasted one and a half seasons; David Susskind produced N.Y.P.D., a frank look at the city’s police with scripts often based on real cases that folded after two seasons.

Preferred were programs the networks concocted that took the troubling issues of the day and delivered them in an untroubling manner. The Mod Squad featured a trio of hippy types but showed them fighting for the status quo; Mission: Impossible had the government’s dirty tricks department furthering the cause of good and right in a series that ran for seven years; Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In tempered the edge of its topical, political, and sexual humor with vaudeville shtick and bikini-clad go-go girls for seven seasons.

On the issue of race, the status quo finally started to give ground although at a snail’s pace. The impulse to change usually came from below, from determined producers, rather than through a mandate from the nets.

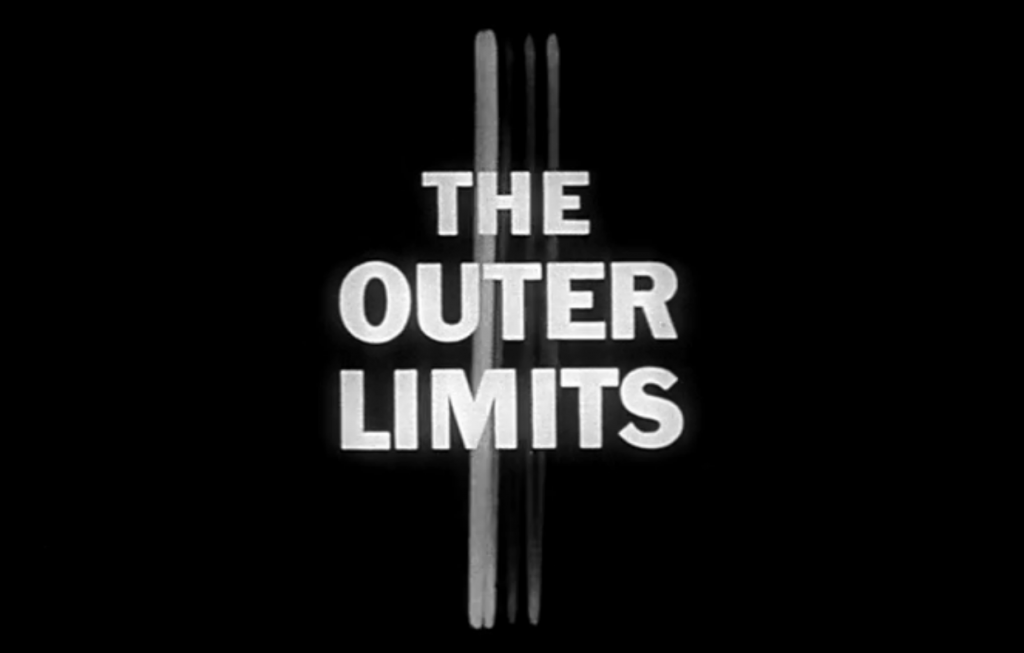

In 1963, producers of the sci fi anthology The Outer Limits cast black actor Hari Rhodes in a supporting part. ABC objected on the grounds that the script had not specified the part called for a black. Producer Joseph Stefano’s reply was to pen in the word “black” on the script.

A few years later, the networks were still queasy treading on such new ground. Take what happened on a third season episode of Star Trek entitled, “Plato’s Stepchildren.” Par for the show, Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and several of his officers, including Lieutenant Uhura (African American Nichelle Nichols) got themselves captured by a nasty superior race of aliens. Well, these “stepchildren” had super mental powers, and one of the ways they decided to amuse themselves was to mess with Kirk’s mind and make him kiss Uhura. What the aliens didn’t care about was that this would be the first kiss across the color line on TV.

If the aliens didn’t mind, NBC did. The way Ms. Nichols told it to David Gerrold in his book, The World of Star Trek, while the net was gutsy enough to allow the kiss, the on-camera compensation had to be that Kirk couldn’t look too thrilled at it. “We played too hard against it,” Nichols told Gerrold. “(Shatner) fought it as if he didn’t want to kiss me.” Afterwards, Nichols said, the mail came in to the show in buckets essentially saying that the good captain had to be out of his planet-hopping mind to fight kissing such an attractive woman.

Still, there were more positive signs. One of the ballsiest moves came from producer Sheldon Leonard. Leonard had begun in Hollywood as an actor. “Sheldon played every Damon Runyon character ever put on screen,” says Bill Persky who worked for Leonard’s production company on The Dick Van Dyke Show. “He was a Bronx guy who spoke out the side of his mouth, but it was always straight talk, and from years in the business and his innate intelligence, the information was always solid.” In 1965, Leonard went full-force at TV’s color line with the globe-trotting espionage series I Spy, casting Bill Cosby as the first black lead on a dramatic series, a role which earned the actor/comedian three Emmys.

Though popular with critics and audiences, I Spy converted neither network wariness nor audience prejudices overnight. Throughout its run, I Spy was banned from a number of southern TV stations, and it wouldn’t be until 1968 before another black performer top-lined a network show, this one the bland but nevertheless groundbreaking sitcom Julia, starring Diahann Carroll.

Bill Persky managed to break some ground of his own on another front with That Girl, a series he created with his partner Sam Denoff, which debuted in 1966. Starring Marlo Thomas as a young wannabe actress trying to make it in New York, That Girl was something of a precursor — even, arguably, an ancestor — to HBO’s hit, Sex and the City, which wouldn’t come along for another three decades. “(That Girl) was the first time a young woman was the star of the show and didn’t have to be living with or working for a dominant male character. (The character of Ann Marie) wanted to be her own person, and had a dream which no one could discourage or take away. She would take any job, face any adversity, and never be stopped.

“(The show) had such great impact on young girls in their teens who, until then, hadn’t thought there were options beyond getting married and being a mother. Marlo was a feminist before there was even a word for them.”

The landmark series most critics generally credit with bringing TV into a realistic present day was producer Norman Lear’s All in the Family, which debuted in 1971. Carroll O’Connor played a lower middle-class blue collar guy, an ill-informed, narrow-minded bigot who wasn’t shy about sharing his rather nasty opinions. The series put the topic of prejudice and just about every other social and political ill out in the open and became a long-running success in the process. It launched an era Josh Sapan describes as TV’s “early adulthood and…the beginning of some socially impactful TV.”

In the years that followed, the taboo against relevant subjects seemed to fade, and so did color lines. All in the Family and Dawn were all highly popular shows with minority casts or leads. Ensemble casts now always found room to diversify the age, race, and gender of their troupes. Cop sitcom Barney Miller, for example, began its long run with a cast that included the proverbial young hot-headed cop, the proverbial wise elder cop, a Latino cop, a black cop, and an Asian cop, all under the command of their Jewish captain. Sexism, rape, racial equality, mental illness, homosexuality: bit by bit, it all came out into the open as well. This age of television glasnost would prompt something of a second golden age for the medium, with such pinnacles as the miniseries’ Roots and Holocaust.

Still, television hadn’t necessarily gotten better on the whole. The Top Ten lists remained dominated by “safer” programs. Take a look at the Top Ten from each year starting with All in the Family’s first season to the year it finally got knocked out of first place by flyweight Happy Days:

1971-72:

1. All in the Family

2. The Flip Wilson Show (variety)

3. Marcus Welby, M.D. (medical drama)

4. Gunsmoke

5. ABC Movie of the Week (weekly made-for-TV

feature)

6. Sanford and Son (sitcom)

7. Mannix (private eye drama)

8. Funny Face (sitcom)

9. Adam-12 (police drama)

10. The Mary Tyler Moore Show (sitcom)

1972-73:

1. All in the Family

2. Sanford and Son

3. Hawaii Five-O (police drama)

4. Maude (sitcom)

5. Bridget Loves Bernie (sitcom)

6. The NBC Mystery Movie (three series alternating

in the same time slot: McCloud, Columbo, and

MacMillan and Wife)

7. The Mary Tyler Moore Show

8. Gunsmoke

9. The Wonderful World of Disney (family anthology)

10. Ironside (police drama)

1973-74:

1. All in the Family

2. The Waltons (family drama)

3. Sanford and Son

4. M*A*S*H (sitcom)

5. Hawaii Five-O

6. Maude

7. Kojak (police drama)

8. The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour (variety)

9. The Mary Tyler Moore Show

10. Cannon (private eye drama)

1974-75:

1. All in the Family

2. Sanford and Son

3. Chico and the Man (sitcom)

4. The Jeffersons (sitcom)

5. M*A*S*H

6. Rhoda (sitcom)

7. Good Times (sitcom)

8. The Waltons

9. Maude

10. Hawaii Five-O

1975-76:

1. All in the Family

2. Rich Man, Poor Man (dramatic mini-series)