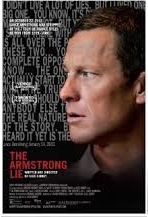

Written and directed by Alex Gibney

USA, 2013

“I gotta win this fuckin’ race,” Lance Armstrong said in his hotel room in 2009, a moment captured on camera and edited into director Alex Gibney’s newest documentary, The Armstrong Lie. Gibney’s voice can then be heard off-camera, his tone agreeable. “My whole documentary is counting on you,” he says. In that moment the audience can see everything behind this picture: what brought these two men together, what lies they were telling to each other and themselves, and why it would take 4 more years for the entire story to be told. And yet, the movie as a whole reveals very little.

Gibney’s original plan was to cover Armstrong’s return to the Tour de France cycling race in 2009, 4 years after Armstrong had won the last of his seven consecutive Tours. Armstrong, whose entire career had been plagued by accusations of doping, was emphatic that the 2009 race would be clean, and prove that he had been clean all along. However, the comeback caused a great deal of animosity among Armstrong’s former teammates, who immediately began to tell their stories of the star’s doping to the media. So Gibney instead opens his film with a January 2013 interview Armstrong gave to Oprah Winfrey, in which he admitted that every single one of his Tour wins had been tainted.

Gibney maintains an obsessive pace as a filmmaker – in the years since his original Armstrong documentary fell through, he’s made 14 films – and that obsession manifests itself here as exhaustive reporting. Every one of Armstrong’s many denials over the past 14 years is documented here, either smashed up into a supercut or contrasted with his later admission of guilt. Each of those denials is a lie, and Gibney reveals the truth in great detail, examining every illegal tactic that put Armstrong’s team on top of the cycling world. Similarly, the 2009 race is captured from a dozen different angles, including from a camera mounted on Armstrong’s handlebars.

However, part of the reason Gibney had to document the 2009 race so deeply is because former Tour de France champion Greg LeMond was also following Armstrong for every centimeter of that race, determined to make what he called the “anti-Gibney film.” At some point, Gibney bought into the Armstrong Lie, to the point that other riders thought he was making a “puff piece” on Armstrong. No amount of exhaustive evidence or in-detail reporting can erase Gibney’s agreeable, even hero-worshipping, tone with Armstrong in that hotel room scene mentioned above. This film is haunted by it.

To his credit, Gibney owns his complicity far better than any other Armstrong defender ever has. He thoroughly explores the ways in which everyone was willing to believe in the story of a man who beat cancer and beat the world’s toughest race, from the international cycling federation to the hosts of The View. Gibney acknowledges his own failures of skepticism every time they’re seen on camera: he uses the words “I” and “me” more often in this film than in every other picture he’s made put together.

Yet it’s not enough. It seems that Gibney makes the same mistake as every defender that Amrstrong once had: they all frame the Armstrong Lie in terms of “Lance Armstrong lied to me” instead of “Lance Armstrong lied to all of us, including himself.” This Rick Reilly column from ESPN.com is an example: he demands that Armstrong make up for Reilly’s “14 years of defending a man … [a]nd in the end, being made to look like a chump”, as though that was the worst deception committed. Gibney is the same, asking in his narration at one point, “What did [Armstrong] know that I didn’t?” Why not ask, what did he know that we didn’t?

The answer is, because everyone takes the Armstrong Lie to heart. Not just cancer patients or friends and relatives of cancer patients, either: everyone who’s ever believed that hard work can lead to success, everyone who’s ever pushed himself an extra mile on his bike, everyone who’s ever felt that this was one of life’s perfect stories … all of them take his admission of guilt right to their cores. Each of them feels that Armstrong lied to him or her, personally; it can even be seen on Oprah’s face during Gibney’s limited sampling of that interview. As a documentarian, Gibney has to rise above that urge to personalize and make the lie matter to every single person that it was told to, but he doesn’t quite get there. Ultimately, that’s what causes The Armstrong Lie to fall a bit flat.

— Mark Young