The Beginner’s Guide

Developed by Everything Unlimited Ltd.

Published by Everything Unlimited Ltd.

Available on PC, Mac

To enjoy this game you have to let it surprise you, but to meaningfully write about it I will have to spoil the surprise. So, if you have not played it yet, stop reading this. What was clever, cold, and schematic in The Stanley Parable is stirring and emotional (deceivingly so) in Davey Wreden’s newest title. Both games share similar features. They’re first-person adventures in which a narrator/designer guides us through corridor-based scenarios that interrogate videogame conventions. Except this time the narrator is Wreden himself, who adds commentary to what he presents as the collected, unreleased, and often unfinished works of his former friend, Coda.

This conceit should be familiar to anyone who’s read Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire or Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves, novels that lampoon academic footnotes and endnotes, and include fictional commentators who appropriate the commented texts and compete with their authors. Wreden does something similar, albeit through a more videogamey paratextual element: the developer commentary, as seen in Portal or Brendon Chung’s Thirty Flights of Loving. (Incidentally, Coda’s games, among them a glitchy first-person shooter and several crude yet visually arresting adventures, resemble Chung’s early experiments, like Barista 2, Bugstompers, and Grotto King. My wild, probably false hypothesis? Coda is Chung.) Like these, The Beginner’s Guide is really short, only 90 minutes long. Yet 90 minutes can take a lifetime to forget.

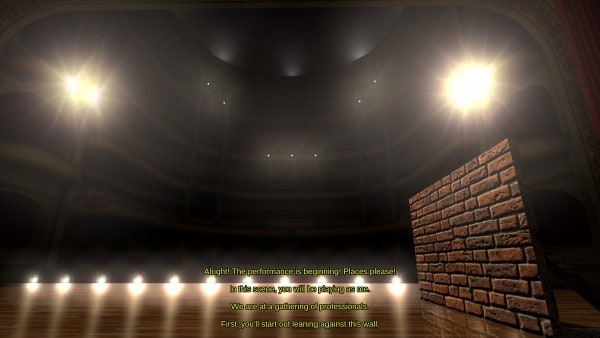

Wreden analyzes Coda’s misfires and quirky masterpieces as we freely move about them. Through his narration, we hear about Coda’s emotional isolation, his withdrawal from social life, and his gradual retreat into solipsism. We discover how his games are thinly-veiled cries for help and companionship, and how he conveys meaning through game mechanics. We walk up a flight of stairs in a landscape of abstract shapes and blocks, and suddenly slow to a crawl for no discernible reason. It would take us years to reach the top and finally enter a room where Coda’s creative ideas float around as magical text. Wreden muses that Coda, in designing this frustrating level, hoped to express the impossibility of truly understanding another human being. To speed things up, however, Wreden allows us to return to normal speed and quickly climb those stairs by pressing the enter key. This sort of oneupmanship occurs frequently, as Coda throws impossible challenges at us and Wreden intervenes to help us out. We eventually wonder whose game we’re playing, since Wreden so liberally manipulates Coda’s code.

As it happens, the answer to that question is ambiguous. Near the end, thanks to Coda’s literal writing on the wall, we realize that much of what we have seen and heard has been Wreden’s invention. As in Pale Fire, the commentator has usurped the author, manipulated the original work, and infected it with his own pain. That is, assuming Coda even exists. At the meta level, Wreden is obviously responsible for everything, including his virtual doppelganger, but the status of the fictional authors is murkier (again, as in Nabokov’s book). Maybe there is no Coda; maybe Coda is a manifestation of Wreden’s fears; maybe Wreden needs Coda to act as a shield between critical audiences and his fragile ego; maybe Coda is Wreden’s earlier, terrified, troubled self, which would explain why Coda’s retirement from game development, in 2011, roughly coincides with the release of The Stanley Parable and Wreden’s rise to cult stardom. (It might also explain his name: we’re playing a coda that looks back at, reflects upon, and bids farewell to a youthful, tortured oeuvre.)

Even if Coda does exist, his games have been found, compiled, stitched together, and openly modified by Wreden. In fact, Coda’s angry wall-scrawls imply Wreden’s influence runs deep: his insistence on coherent game solutions (a reflection of what he wants out of life) affected Coda’s own design ethos. It ultimately doesn’t matter who did what, however, because all works of art are collaborations. Authors cannot help but respond to perceived audiences, while audiences cannot help but add something of themselves into the creations of others.

Moreover, Wreden preemptively complicates any critical, interpretative approach by including a questionable example of one – by his double, no less – within the narrative. In trying to solve such puzzles of meaning, are we not, like the narrator, talking more about ourselves than about the author’s intentions? And since Wreden casts himself as player and commentator in The Beginner’s Guide, can we not say all creators are also audiences and critics? After all, both The Stanley Parable and The Beginner’s Guide are shrewd analyses of video game clichés and genres, and thus function as elaborate pieces of criticism.

The Beginner’s Guide even works as a commentary on The Stanley Parable. When we contradict the narrator in the latter, tearing at the seams of his digital chambers, his nervous breakdowns are always leavened by irony and humor. We smile more than we wince. But when Wreden opens himself up to us, we cannot so easily feel untouched by his misery. Sure, he’s unreliable and deceitful at first, toward Coda and the player, but he eventually comes clean. Although he could, he does not erase Coda’s incriminatory wall-scrawls, which rail against Wreden for releasing these games without authorization and, worse still, ornamenting them with a false biographical context. But might Wreden be manipulating us? Does he really come clean? His apparent endgame honesty remains part of the fiction, it’s honesty by design. And he lies about one crucial thing, too: in-game Wreden is not the real Wreden. So we can doubt everything else, including the narrator’s final meltdown.

If we had reason to distrust the narrator in The Stanley Parable, our misgivings are even more justified in The Beginner’s Guide. Both games trace the limits of player agency and freedom, asking how much of either there is when designers can determine our movements. This sophomore effort deepens the conversation, pointing toward our unique, personal experience as the true continent of our freedom. Doubting the designer, before, was about defying him through actions that opposed his orders; now, in this new game, we also do so through our interpretations and ideas, which deny or at least complicate those fed to us. Our relationship to the designer is not a binary choice between obedience and resistance, but a sustained discussion. What can we do in a created digital environment and what can we think about what we can do?

The best “walking simulators” don’t lack interactivity so much as they communicate their themes through that lack. We expect to interact, but cannot. We attempt to touch objects in Dear Esther, but come away feeling like immaterial ghosts. We hope to break free from the endless corridors in The Stanley Parable, but are only further ensnared in the narrator’s maze. In this case, the rudimentary puzzles, simple level design, and straightforward interaction all emphasize the amateurish, embryonic nature of Coda’s little sketches, cobbled together and tweaked by Wreden. The Beginner’s Guide is not itself amateurish, of course. Its sophistication emerges when we consider the combination of its primitive pieces. The linearity of each chapter means we do specific activities that convey blatantly obvious messages. Yet the game asks us to look beyond what we do, what we see, and what we hear, to take none of these elements for granted and find our freedom in our decision to believe none of it, unless we want to.