The Grandmother

Written by David Lynch

Directed by David Lynch

USA, 1970

Mrs Bates lived on inside Norman’s fractured psyche.

Her continued residence compensated for the guilt her son felt following her murder. Ever present, her spectral presence kept watch in the guise of a maternal superego overlooking the Bates motel from close quarters.

Psycho was one of many Hitchcock films in which the master of suspense would allow the repressed trauma of the Real to trickle through and threaten the stability of a carefully constructed ‘reality’. Maternal anxiety would again occur in The Birds by way of its eponymous creatures wreaking havoc on the townsfolk. The verbal contract in Strangers on a Train, epitomised in the kernel of a single cigarette lighter, refused to die a quiet death. And in Rear Window, Jimmy Stewart’s LB Jeffries saw in the apartments opposite his own – surrogate frames for the cinema screen itself – scenes that fed into his apprehension of married life with Grace Kelly’s Lisa.

While Hitchcock preferred to have the Real return in a tense, concealed fashion through blots in the fabric of his films, David Lynch instead chooses to place ‘reality’ horizontally alongside fantasy, forcing the two planes of existence to collide in an enigmatic tapestry of violently disruptive surrealism that deigns to prise apart the facade and force the characters to confront their desires and traumas. This exposure and decomposition of ‘reality’ is a far cry from conventional sanitised Western products that encourage the perpetual desire and perversion of our everyday ‘reality’ through the gift of implausible Hollywood solutions and closed endings.

In Lost Highway, Bill Pullman’s Fred is confronted by the trauma of the Real through the videotapes sent to his house. By the film’s end, his superego in the form of the disturbing Mystery Man chases him with a video camera, signifying in self-referential fashion that the camera – and in a larger sense, confrontational cinema – is key to an acknowledgement of the Real and a break from pretence.

Mulholland Drive exposes Hollywood’s exploitation of the possibilities of fantasy. It deconstructs the patriarchal order in order to acknowledge not just our position as desiring subjects, but female subjectivity as well, because it relates to how Naomi Watts’ Diane is a spectator to her object of desire within the two worlds of fantasy and desire. Mulholland Drive fully gives way to fantasy at its conclusion and as a result completely immerses itself in illusion, further than any other Hollywood film dares to tread. Lynch’s films are dually engrossing and confounding precisely because they blur the line between fantasy and reality, bringing the two worlds crashing together with often violent results.

Lynch’s third film, The Grandmother, a mix of dark, disconcerting animation and live action, was a logical step following his first two shorts, Six Figures/Men Getting Sick (Six Times) and The Alphabet. Funded by AFI to the sum of £7,200, the finished product was powerful enough to guarantee Lynch a place on their Centre for Advanced Film Studies, in addition to garnering a number of festival awards for the young director.

This prescient 33-minute short serves as a precursor to the predominant themes that would define Lynch’s eventual filmography. Unlike the frustrated adults struggling to reconcile desire and fantasy in his later films, the young boy in The Grandmother still possesses a hopeful belief in the escapist potential of the artistic creation. Imbued with this conviction, he attempts to coordinate distinguishable realms of both an untenable reality overwhelmed by sadistic parents, and the solace of fantasy, personified in the benevolent grandmother whom he grows from soil and seed in a neglected attic room.

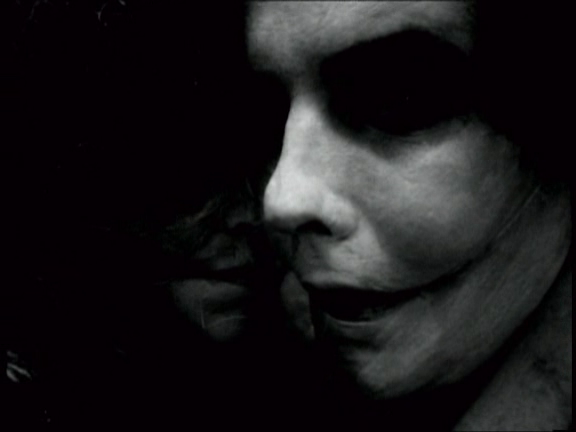

The placement of the attic atop the staircase recalls the higher plane in which Mrs Bates resides. The boy climbs to the apex of the house to visit his grandmother, casting her in the role of a superego, regulating this child’s reality on his behalf. The parents’ status as an animalistic id further supports this proposition; barking like ferocious wild animals, they crawl on their hands in the knees in the dirt. Their pale skin is coloured only by hollow, darkened eyes.

The first of many illustrative animations begins the film, displaying the act of reproduction which results in the birth of a son. He emerges in a separate frame, removed from his parents’ field of empathy. Upon witnessing him sprout from the soil, they charge towards him in carnal rage, regarding him as an autonomous entity open to attack.

In contrast to his elders, the boy is dressed in a smart black tuxedo and resides in a neat, minimal room of limitless black space occupied by a single white bed. When he wets the bed – displayed as an absurd, flat orange patch on the bed sheets – his father admonishes and abuses him, rubbing his face into the urine. Considering the smart appearance of the boy to symbolise the outward projection of the ego, it is apparent that the parents’ abuse is a displacement of guilt for allowing the form of the ego to have its untarnished exterior blotted by a perverse function ordinarily reserved for the id. The fulfilment of these individual roles is exemplified in the tiered placement of the characters, including the title character, within and outside the household.

Consistently berated by his own flesh and blood, the boy creates his own idealised relative using a vacant bed, a mound of dirt and a bag simply labelled ‘seeds’. The child moulds his creation into fruition singlehandedly, creating a fully formed human being outside of the conventional mode of human reproduction. He returns regularly to maintain an eye on its progress, nurturing its growth with the aid of a watering can, by patting the soil and stroking the branches of the tree, pre-emptively forming a relationship with his ‘offspring’. The paternal care displayed contrasts the manner of his own parents, sat slack-jawed and hostile on the occasion whereby he emerged from the earth’s soil, alone and confused.

Soothing music overlays the interaction between the boy and his grandmother, which includes a shared smile at once heart-warming and typically sinister, a foreboding visual gesture quintessentially Lynchian. In this idealised instance, the fantasy element of artistic creation comes to the fore. As the child’s artistic product, the grandmother’s sole created purpose is to placate his desire, to fill the void and provide relief from the trauma of his daily reality. The analogousness with the function of cinema is exemplified by the slow fade on a freeze frame of the two characters kissing – an accustomed symbol of ‘satisfactory’ silver screen culmination.

But as Lynch would demonstrate with his following films, the constructed world of fantasy is inherently fragile and threatens to be permeated by jabs of the Real before its entire texture is torn apart and exposed in its entirety. The grandmother perishes through inexplicable circumstances that see her struggling to breathe, flailing helplessly in a series of swift, successive edits. The boy calls on his parents to help but ultimately fails to reconcile the two worlds of fantasy and desire which he had thus far endeavoured to retain as oppositions. The film concludes with a final shot of his despondent face, resigned to his blank white bed after a brief tryst with an unsound dreamscape. Like the lead characters in Lost Highway and Mulholland Drive would come to realise – in considerably more violent fashion – this child is cursed with the mature realisation that alleviation catered for by escapist creations is merely a transient distraction from a perennial trauma.