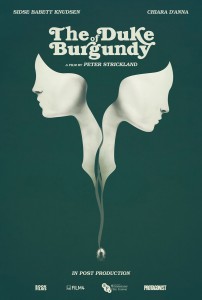

Written and directed by Peter Strickland

UK, 2014

With a narrative built on repetition – the cyclical nature of seasons, feelings and passions – The Duke of Burgundy’s unique structure defies traditional plot and narrative in favour of sensations and experiences. The film most notably has credits in the opening sequence for both the choice fragrance and the lingerie designs, a hint at the precedence luxury and sensuality has within this world. It becomes abundantly clear that breaking the film down in terms of plot betrays its absolute appeal as a masterpiece in haptic vision. (‘Haptic’ refers to ‘touching with your eyes’, though how can we similarly evoke the sensation of smell? Film criticism is lacking in this regard. We need an extensive study on the evocation of smell in cinema, just as there are studies on the way filmmakers conjure sound and music in silent cinema.) Written and directed by Peter Strickland, the film is about a lesbian couple engaged in an increasingly escalated S&M relationship, and when they’re not role-playing, they are lepidopterists (they study butterflies and moths).

Far from adopting a dark and serious tone, the film thrives on its comic vision. Sex is seen not as a vice or a virtue, but merely a preoccupying force in a sensuous, matriarchal parallel universe. This is a world of the female and her sexual occupations. Removing the male almost entirely, the film focuses in on the trials and tribulations of a very feminine relationship that is perhaps coloured by obscured expectations of patriarchy. The age difference, the differing sexual roles, and the increasingly grandiose demands and toys associated with their play are explored with with a sense of (sometimes) joyful exasperation. This not only injects warmth into the interactions, but also peels back the many layers that exist within their relationship. Perhaps, most elusively, it is the love and affection that drives their interactions. As one player does not seem to revel as completely in the sexual power games as the other, her motivation is not control or pleasure, but rather love for her partner. The frustration drives both conflict and poetry between the two, as the push and pull of their interactions has effects small and large on their routine.

The skill of Strickland’s filmmaking is that he is able to convincingly maintain the routine of the women without falling too deeply into redundancy. He does this by continually shifting focus, as he reveals more and more of the relationship and universe of the characters. By the time the audience has become accustomed to the routine and habits of our leads, breaks in that structure feel significant. As the original impression of reality also begins to crack, the strict artificiality of their relationship begins to take hold. Adopting an almost subversive take on artificiality though, Strickland does not suggest the role-playing and decorative living of his characters is somehow insincere. In a film that feels so wildly female, this feels groundbreaking – rather than being dismissive of the preoccupations, roles and luxuries of female life, the film suggests their utility and their importance removed from the need to be pleasing to a man. Though the film does reserve some apprehension about some aspects of this culture, they are not motivated by exterior forces but rather the interior world of the character’s themselves. The film’s repetitive structure similarly makes the pointed interruptions of seminars on butterflies and moths all the more poignant, as they reveal the nature of love and sex within the public space as existing in both conflict and service to the private space.

The true definition of haptic vision sees it often associated with the tactility of the medium itself (the textural qualities of 35mm or the granulation of digital), and in this regard the film does not necessarily meet the criteria. There are moments that exceptionally meet the bill, such as the extensive final act homage to Stan Brakhage’s Mothlight (1963), which some have argued is little more than a rip-off, but I’d probably argue is an essential and risky act in tonality and point of view. It not only ties in nicely with the moth/butterfly motif, but suggests more deeply the performance and decorative aspect of female sexuality. It is an exercise in tactility, which similarly harkens to the film’s deep obsession with sensuality. However, I’d argue that haptic vision should be extended to cinema that suggests the sensation of touching. That would include a large bulk of erotic and horror cinema, and perhaps pornography is, by its very nature, haptic (but wide-sweeping generalizations like that will always be argued and disproved, so I only feel comfortable suggesting it as a possibility rather than a truth).

The Duke of Burgundy is a rare film that seems to get to the heart of S&M relationships without being flippant or gratuitous. The key to understanding the film is to begin unravelling where the power actually lies. Strickland creates a film that thrives on sensations, the textures of materials, the wafting mists of perfume, the pointed sound of urination… this is a film where style is substance, because it reveals continually the inner workings and transformations of the characters. While The Duke of Burgundy certainly won’t appeal to all tastes, it is a must see for the curious and the adventurous; a wondrous experience in eroticism, sensuality and love, and one that will likely stand up as one of the year’s best films.

— Justine Smith