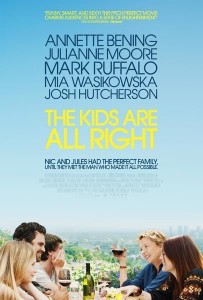

Directed by Lisa Cholodenko

Written by Lisa Cholodenko, Stuart Blumberg

2010, USA

It landed on many critics’ end-of-year top ten lists, and has been nominated for four Oscars. So now comes the inevitable question of whether The Kids Are All Right, director Lisa Cholodenko’s dramedy about what ensues when Paul (Mark Ruffalo) is contacted by the teenage children of the lesbian couple (Annette Bening and Julianne Moore) to whom he donated his sperm, is really worthy of all its accolades. The answer to said question ultimately depends on whether one perceives Cholodenko and her co-writer Stuart Blumberg’s apparent lack of a socio-political agenda as a sign of greatness, or simply a safety net threatening to suffocate the film into blandness.

This is not to imply that The Kids Are All Right is lacking indisputable strengths. Blessed with two of the finest working actresses today, (for all the deserved praise they’ve received for their performances, shame on he who ever really doubted that Bening and Moore, with such strong resumes as theirs, would be able to pull off playing a lesbian couple), as well as two promising, natural young actors (Mia Wasikowska and Josh Hutcherson) playing the couple’s children, Cholodenko is able in the first twenty minutes to introduce the viewer to a genuinely warm, well-adjusted, and endearing family unit. Furthermore, rather than run the risk of seeming preachy and falsely utopic, Cholodenko and Blumberg assure us that this family, for all its functionality, is far from perfect. And if the family’s minor issues seem formulaic enough for a sitcom, (Bening’s a control-freak who hits the sauce a bit too much, Moore feels neglected and criticized, Wasikowska feels pressured to be the perfect daughter, Hutcherson’s friend is a bad influence, etc, etc), I suppose it is the very familiarity of these plot points that allows for the (questionably still mandatory) “Look! This family isn’t so different after all!” reaction from the audience.

actresses today, (for all the deserved praise they’ve received for their performances, shame on he who ever really doubted that Bening and Moore, with such strong resumes as theirs, would be able to pull off playing a lesbian couple), as well as two promising, natural young actors (Mia Wasikowska and Josh Hutcherson) playing the couple’s children, Cholodenko is able in the first twenty minutes to introduce the viewer to a genuinely warm, well-adjusted, and endearing family unit. Furthermore, rather than run the risk of seeming preachy and falsely utopic, Cholodenko and Blumberg assure us that this family, for all its functionality, is far from perfect. And if the family’s minor issues seem formulaic enough for a sitcom, (Bening’s a control-freak who hits the sauce a bit too much, Moore feels neglected and criticized, Wasikowska feels pressured to be the perfect daughter, Hutcherson’s friend is a bad influence, etc, etc), I suppose it is the very familiarity of these plot points that allows for the (questionably still mandatory) “Look! This family isn’t so different after all!” reaction from the audience.

But this is, after all, a movie, and there has to eventually be some kind of crisis for the sake of dramatic effect. Here, it comes in the form of Moore’s sexual affair with Ruffalo, subsequently releasing the bottled-up tensions of her entire family. The screenplay, however, is surprisingly superficial about examining the complexities of the situation. Yes, we get the soul-baring and emotionally-heated climactic exchange between Bening and Moore, but this also happens to be where the dialogue is at its most leaden and contrived. Indeed, one of the most frustrating aspects of The Kids Are All Right is how it blends expertly executed scenes that are subtle, tense, and often lightly farcical in their examination of what’s not being said, (any scene with the five leads seated around a dinner table is a highlight), with moments that seem more suited to TV melodrama, featuring such lines as “Sometimes you hurt the ones you love most,” and “Maybe it hasn’t reached your plane of consciousness yet.”

But this is, after all, a movie, and there has to eventually be some kind of crisis for the sake of dramatic effect. Here, it comes in the form of Moore’s sexual affair with Ruffalo, subsequently releasing the bottled-up tensions of her entire family. The screenplay, however, is surprisingly superficial about examining the complexities of the situation. Yes, we get the soul-baring and emotionally-heated climactic exchange between Bening and Moore, but this also happens to be where the dialogue is at its most leaden and contrived. Indeed, one of the most frustrating aspects of The Kids Are All Right is how it blends expertly executed scenes that are subtle, tense, and often lightly farcical in their examination of what’s not being said, (any scene with the five leads seated around a dinner table is a highlight), with moments that seem more suited to TV melodrama, featuring such lines as “Sometimes you hurt the ones you love most,” and “Maybe it hasn’t reached your plane of consciousness yet.”

Furthermore, by scapegoating the Mark Ruffalo character in the end, the aftermath of Moore’s infidelity, which is

I am fully aware though, that in lesser hands, The Kids Are All Right might have been bloody awful: For instance, it could’ve been preachy about gay parenting, and the Moore character could’ve questioned her sexuality after sleeping with Ruffalo, who would turn out to be a complete ne’er-do-well. The fact that the film is sophisticated enough to avoid any of the above mawkishness is a step in the right direction. However, even if one applauds its apolitical nature, there is still something a little too self-effacing about the film that makes it almost as generic as the California suburb it’s set in. No matter how endearing her unique family is, by keeping them in tried-and-true scenarios, and never truly getting to the heart of them, Cholodenko often risks inspiring the horrible thought of “If I’m really not supposed to care that they’re lesbians, why am I watching this in the first place?” One hopes that when we next hear from Chodolenko, the “warts and all” aspect of her storytelling will consist of much more than a bunch of close-up shots of well-known actresses without makeup.

– Jonathan Youster