By my teens, we were living in the suburbs, but I could still hoof it to a flick. At one end of my town’s main drag was the Park Theater. Later, when the Park converted to a classics/art house, there was still the Cinema West at a new strip mall at the other end of the same avenue.

And if we couldn’t find something at either the Park or the Cinema West, a ten minute bus ride took us to the next town and the Verona, or another five minutes on the bus and we were at the Clairidge or the Wellmont. If it was a warm night, it wasn’t unusual for us to hike back, stopping off at an IHOP for a midnight snack.

I attended the University of South Carolina whose main campus sat just a few blocks from downtown Columbia which offered four theaters within walking distance (not counting the porn house just a block off the main street).

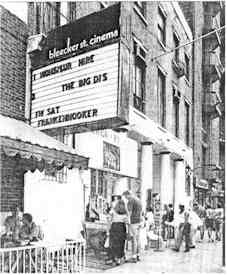

In fact, for most of my life, there was always a movie theater within easy reach: a good walk or a short ride. Even when I started working in New York and was introduced to the Manhattan art house circuit, most of them were never more than a 10-minute subway ride from where I worked: the uptown Carnegie where I saw Kiss Me Deadly (1955) for the first time, or the Thalia for a George Pal double bill, the Hollywood Twin on the West Side which was a converted porno house where I first managed to see one of my all-time favorites – The Wild Bunch (1969) – uncut, and one of the landmark American art houses, Greenwich Village’s Bleecker Street Cinema.

By the time I got out of college, a lot of the theaters I’d grown up with were gone. I didn’t think much about it – things come, things go, way of the world and all that – until I stopped by my high school to visit Mr. Berisso, an old science teacher of mine and a damned decent guy. Beripp (I have no idea why we called him that) used to put in a fair bit of after-hours time working with students, advising on this, working with them on that. He was a teacher who cared, and that care extended beyond the classroom.

We were talking about the demise of the local movie houses, and how now kids had to badger their parents to trek them out to the nearest mall and its multiplex. He called it part of the “disenfranchisement of youth.”

I never forgot that. Disenfranchisement of youth. The corner store hangout had been replaced by indistinguishable 7-11s. The stationary stores with their racks of paperbacks and horror comics were replaced by — … well, they weren’t replaced at all; they just disappeared. And so did the local movie house.

For the generation (actually, two, I think) which has grown up in the multiplex environment, it may even be beyond comprehension that, at one time, movie-going was predominantly a neighborhood activity. All but the smallest towns had at least one boxy little bijou on Main Street, and the big cities usually had – along with a nest of them downtown — others scattered around the neighborhoods. They were like fire houses: every part of town had one. The movie house and movie-going was part of the fabric of the neighborhood.

I was thinking about this because I came across a story in my state newspaper a week or so ago about one of the few remaining neighborhood single-screen theaters in New Jersey. Most single-screen houses tend to be art houses and homes for oldies, but this one wasn’t. The thing about these single-screen houses is – art house or mainstream commercial – the people who run them do so more out of passion than commercial enterprise. They have to; there’s not enough money in it to do it for the money.

And so it is with this particular house. The guy who runs it knows his audience; he knows how to tailor his offerings for them, knows what they’ll respond to and what they won’t. He doesn’t have the latitude a multiplex manager has who can offset a clunker in auditorium #6 with the hit in auditorium #12. Like any single-screen house, this guy’s fortunes rise and fall week to week, and his connection to his neighborhood – knowing his people — is what keeps him on the plus side more than the minus.

And now it looks like this house going to fold. Permanently. And maybe a lot of others like it.

The problem is the switch from film to digital technology. There’s something like 39,000 movie screens in the U.S., and maybe 10% of them have already converted to digital with an average of 400 joining their ranks every month. For the corporations that own the multiplex chains, that’s an expensive switchover, but one considered a necessary investment in the future. You can argue the quality of digital v. film, but you can’t argue the long-term cost efficiency of digital. Conventional prints are bulky, expensive to ship, cost anywhere from $1500-2500 (or more) per to produce, and can degrade over time unless properly stored (another expense). None of that applies to digital.

But it’s one thing to ask a big chain to fork out the money to convert its auditoriums. It’s another thing for a little mom-and-pop, stand-alone, single-screen house to come up with the money…and some of them can’t. At some point, the American motion picture industry will be an all-digital business, and those who can’t make the transition are going to close their doors.

In terms of the industry, those closures will hardly be a blip on the graph. There’s not enough of them for their box office contribution to make much difference up or down, so the only real loss is nostalgic. I admit it; nothing more than that.

I know I sometimes tip over into the overly sentimental, that I’ve sometimes been accused of spending more time looking over my shoulder than ahead, and one commenter even labeled me an “old fogey.” But give me this one.

When the last of these single-screen houses shutters for good, it’ll be the end of the last vestiges of a certain kind of movie-going…and a certain kind of movie.

In a time where there weren’t nearly as many entertainment options as there are today, movies – even the supremely crappy ones – were a bit more special. And the local theater, well, maybe this sounds silly, but that was our movie house – not a movie house.

You grow attached to the stupidest things, and you don’t even realize you’ve grown attached until some years later, you look back on them and realize you miss them. Like milk men, the local book store (I don’t mean like a Barnes & Noble behemoth, either), the corner store with the ice cream counter in back. And I miss them more now that I can’t share them with my kids; that I can’t walk the few blocks to downtown and take them to a movie (we had a local movie house when we moved here; they tore it down within the year and replaced it with a plaza).

My first theater, the Elwood, that’s a White Castle now. The Park burned down and there’s a bank there, and the strip mall where the Cinema West was plowed it under and extended its row of shops. The Wellmont became a concert venue, the Clairidge carved up its Cinerama cavern into a half-dozen little boxes, and the Verona is an office building. All those movie theaters I used to walk to in Columbia are gone, and so are a lot of the Manhattan classics houses. When the Bleecker Street Cinema folded in 1990, a victim of rising rents, its passing was written about as they might’ve written about the burning of the Library of Alexandria 22 centuries ago.

Sometimes I tell my kids stories about going to the movies when I was a kid. They can’t believe the cheap prices, the door prizes, the way we weren’t chased out between shows. I think most of all they couldn’t believe our independence, and how at ease our parents were with it.

“Boy,” one of them said to me, envious, “I wish we could go to the movies like that.”

“So do I,” I told her. “So do I.”

Bill Mesce