Directed by Gore Verbinski

Written by Justin Haythe & Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio

USA, 2013

Sincerity is in dire need of being resurrected in modern popular culture. This is not to say that cynicism doesn’t have a place in society, or that naivete should be widely embraced by the masses. But being smug and snarky only takes you so far, as proven by The Lone Ranger, a film that suffers from many problems, not least of which is its embarrassment that it’s a story about the Lone Ranger. There is nothing wrong with centering a big-budget tentpole movie around a good, old-fashioned hero, yet The Lone Ranger desperately runs away from such an open, welcoming spirit, headlong into unpleasant, sluggish chaos.

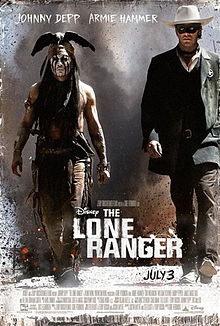

The first mistake of many is that Johnny Depp, who transformed his quirky personality just slightly enough to become a movie star in 2003 as the perpetually soused Captain Jack Sparrow in Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, is the lead here. Depp plays the mysterious Comanche tribesman Tonto. “But, wait,” you may wonder. “Isn’t Tonto the sidekick?” No longer, perhaps because Depp—now an honorary Comanche—feels the urge to treat the Native American community with respect, or because he wouldn’t do the film as the masked man himself. Either way, Depp is now Tonto, first glimpsed in San Francisco in the 1930s, looking eerily like Miracle Max from The Princess Bride. Through a pointless flashback structure that teases more meta humor than it delivers, he weaves the tale of how he first met well-meaning, but bumbling attorney John Reid (Armie Hammer, surely having now done enough penance for cutting an almost comically handsome figure in movies like Mirror Mirror and The Social Network), and ended up fighting together for justice in the Wild West in any form.

How John Reid, who’s almost afraid of holding a gun let alone using one, becomes the feared and deadly Lone Ranger takes up the entirety of The Lone Ranger, but is framed through Tonto’s perspective. As such, Reid is never allowed to be the ultimate good guy, riding atop his trusty steed Silver, not unless Tonto can undercut him with a one-liner or a cartoonish roll of the eyes. Yes, this is a reinvention of the Lone Ranger, and while the character is likely unfamiliar to modern audiences, the hallmarks of the character are burrowed deep in pop culture. The line “Hi-yo, Silver, away!” is uttered here, but only as a set-up to a mocking punchline. Why make a movie about the Lone Ranger if the chief goal is to, in essence, lob spitballs at him? This tactic, woven throughout the script by Justin Haythe & Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, constantly undermines our hero for no discernible reason aside from an utter lack of comfort at presenting a tried-and-true winner without any reinvention. Playful jibes at the hero can work in an action movie, but it turns almost into scorn here.

The lack of hero worship is but a scratch on the surface. The Lone Ranger is ostensibly a reunion of guaranteed summer-movie talent: aside from Depp and two of the film’s writers, this was produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and directed by Gore Verbinski. Bringing the Pirates of the Caribbean crew back together would seem a winning combination, but this movie doubles down on the unpleasantness that dotted the first three Pirates films—such as the grim moment where, for no decent creative reason, a crow pecks out a man’s eyeball on screen. Walt Disney Pictures still makes movies the whole family is, one assumes, meant to enjoy, but only now can they brag that they’ve finally depicted cannibalism onscreen. Yes, to emphasize how odious the lead criminal, played by a scarred William Fichtner, truly is, we get to see him act out upon his most ravenous instincts. Do we need more proof that said villain, Butch Cavendish, is nasty and hissable after he slaughters some lawmen, or after threatening to rape the hero’s love interest while her son stands by helplessly? Here and in other sequences, as when a military attack on a Comanche tribe is depicted in full, The Lone Ranger simply is unnecessarily ugly.

Verbinski, it’s not hard to assume, wanted to present as accurately, as possible in a PG-13 environment, what it was like to live in the Wild West. We may like to believe that as the world progressed, and the railroad was built from coast to coast, life was happy and devoid of violence or fear. This was not the case, of course, so it makes sense that the Lone Ranger would fight on the side of right and good. How Verbinski chooses to visualize this battle, however, is nasty and frequently dissonant; immediately after that slaughter on the Comanche, there’s a random, nonsensical joke involving Silver and a tree. Would it be funnier if it didn’t come on the tail end of a violent scene rooted in the dark history of the United States? Maybe. But jumping from one extreme to the other only incites cognitive whiplash. Basically, it’s difficult to be as fleet and exciting and funny as the original Pirates of the Caribbean while attempting to acknowledge the grim reality of how the West was expanded, if not won.

Technically, as well as among the ensemble, The Lone Ranger is predictably top-notch. There are far fewer CGI effects here than in the Pirates films (or so it seems), and Verbinski is, if nothing else, adept at staging action sequences. The film is bookended by runaway-train setpieces, the latter of which is scored to a slight update of the William Tell Overture, also known as the Lone Ranger’s theme song. Hans Zimmer, the film’s composer doesn’t undercut the Lone Ranger’s mythology aurally; on its own, the climactic action sequence is impressively pulled off. The triumph with which the scene, and overture, end, however, is undeserved and unearned; why should we cheer and applaud a hero the movie is so unwilling to embrace?

Armie Hammer comes off well, even if his John Reid is nothing short of a buffoon, one who’s branded a coward for wishing to follow the due process requirements of the American legal system. He is, thankfully, game to be the dapper clown. Regarding Tonto, it’s only slightly reductive to say that Johnny Depp plays him as a slightly tweaked Captain Jack Sparrow. He’s goofy and strange—and the explanations for such affectations as the dead bird atop his head are meager—but really, he’s just a bundle of oddities in search of a personality. Aside from Fichtner, the real standout is James Badge Dale, as John’s Texas Ranger brother Dan, who’s dispatched early on so that John will get a taste for revenge. Inside and outside the movie, the problem is the same: Tonto wanted Dan to help him capture Cavendish, because he’s the prototypical warrior-hero. Hammer’s performance aside, Dale has proven in recent years that he’s a shrewd, unpredictable, compelling actor; maybe it’s time someone gave him a chance to shine outside of memorable supporting roles.

The Lone Ranger is another nail in the coffin of sincerity in Hollywood, a bloated and excessive would-be epic that doesn’t believe in its own hero’s journey. It’s easier in life to be winking and churlish. It takes effort to admit that maybe, just maybe, watching an old-school hero can be fun, too. Such a stand is one that takes guts; it’s a risk that Gore Verbinski, Johnny Depp, and the rest are unwilling to take. There may be few Lone Ranger purists out there, and there’s nothing wrong with shaking the character up so he feels less stodgy and more current. But there’s something strangely bothersome and wrongheaded about turning the titular good guy into a court jester, simply because it’s easier than making him a straight-shooting, white-hatted force for the best of humanity.

— Josh Spiegel