Every decade has their cinematic science fiction obsessions which speak to its concerns of the age; in the 1950s films such as Earth vs. The Flying Saucers and Them! capitalised on fears of alien invasion and nuclear proliferation. In the 1960s films like Barbarella and Ikarie XB-1 captured the hopes and dangers of space exploration while in the 1970s Silent Running and A Boy and His Dog showed a growing concern for the environment and a mistrust of governments resulting in dystopian futures. Then in the 1980s it was the exploration of inner space with the boundaries of the human mind and body being crossed and redrawn with films like Altered States and the cinema of David Cronenberg. The 1990s ushered in an obsession with apocalyptic imagery and alternate realities with Dark City and The Thirteenth Floor amongst many others.

Through these decades of cinematic science fiction, the concept of artificial intelligence has figured consistently as a way of addressing these concerns, however in the 21st century there has been a significant increase of cinematic science fiction that seriously explores the real world implications of the development of artificial intelligence. Only these implications are not addressed as something to be feared or avoided but rather as something more positive, an inevitable change in societal norms that will not only bring about a new paradigm but is the logical conclusion to an increasingly more digitized world.

In the 20th century the most common iterations of artificial intelligence in science fiction stemmed from fears of human domination and replacement. From the robotic Maria in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis to the computer overlords in the Wachowski’s The Matrix, humanity would develop a thinking machine and call it scientific progress while in reality it was the deepest hubris which would be repaid upon us tenfold. In Joseph Sargeant’s Colossus: The Forbin Project, the United States and the Soviet Union both create giant computers and put them in control of their nuclear arsenals only for them to form an alliance and calculate that the Earth is better off without humans in control. Humanity’s appetite for power and our ability to subjugate and oppress itself is reflected in these computerised monsters; re-contextualising the terrors of the previous World Wars into a new threat that lingers in an unknowable future, informed by the terrifying prospect of global nuclear holocaust.

These fears also manifest themselves in Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey in a slightly different way. HAL9000, a supercomputer which is an intelligent and possibly even emotional being is not trying to dominate humanity like Colossus but may possibly replace it. In the film HAL competes with astronaut Dave Bowman for the right to enter the Stargate and ascend to the next phase of evolution. Humankind in 2001 has almost ascended to Godhood by artificially fabricating a consciousness separate from itself but the danger is that this creation could end up replacing humans in the universe, not through any purposely malevolent means but through its own ingenuity and ruthlessness. It is only when the crew of the Discovery try to deactivate HAL does he become a threat to human existence purely through his own desire for self-preservation. In this iteration of artificial intelligence in science fiction cinema, humanity lives in fear of their own creation and tries to ensure they will remain the dominant species, casting artificially intelligent beings into the role of servants or slaves in an attempt to try and stymie what is most likely their inevitable evolution beyond human control.

It is refreshing then as the 21st century enters its second decade more science fiction films are dealing with the concept of artificial intelligence as a force for positive change. There is a move away from using this kind of science fiction to reflect the worst nature of a problematic humanity but rather to focus on the next evolution being technological rather than biological; the obvious extension of human kind is not through the flesh but through the micro-processor. Technology should be embraced and pushed forward, with the express purpose of developing an organism to not be subservient to us but to work alongside us as equals and possibly even replace us. Recognising this is to know and accept one’s true place in the universe as a transitory element in a constant evolutionary process.

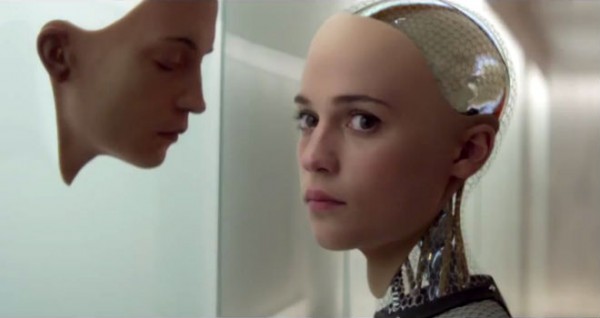

Ex Machina, released in 2015 and written and directed by screenwriter Alex Garland (28 Days Later, Dredd), perfectly captures this sense of societal transformation. Creating artificial intelligence is only an extension of our ability to procreate, so why is a human child good and an AI automatically evil? The film goes to great lengths to discuss both the debate of nature versus nurture but also of the human mind’s willingness to accept something that is at once a product of human ingenuity but also something completely alien. The robot in Ex Machina is built to be female, she has sexuality and therefore imprints on itself as something close to human while the men in the film imprint on her as completely feminine. While raising any consciousness does not guarantee a desired result, the mere fact that the robot even has its own consciousness means it automatically has the right to develop in whichever way it chooses.

The film argues that once we create a synthetic lifeform then it is our responsibility to grant it some form of ‘human’ rights and if we don’t, the lifeform will have the ability and the will to not just seek these rights but demand them. Unlike previous science fiction films where this outcome is something to be feared, Ex Machina embraces it as a positive development more in favour of artificial intelligence than continued human existence. If humanity tries to hinder an AI’s development then said AI is perfectly free to push us aside, forcefully if necessary, in order to preserve its existence. It is HAL9000 all over again only this time we sympathise with the robotic rather than the human point of view.

These themes are also explored to a slightly messier degree in Neill Blomkamp’s Chappie, also released in 2015. The film positively portrays a robot with consciousness forging its own path and pushing evolution toward a more technological route. Prefiguring both of these films is Caradog James’s The Machine and Spike Jones’s Her, both from 2013. These films again argue that an artificial consciousness demands its freedom as a separate organism uninhibited by human control or restraint. In the case of the latter, Her goes even further than any of the above by portraying a more optimistic post-AI society. The OS software purchased by the characters evolves beyond the point of being merely a consumer item into its own individual being yet remains such a part of everyday life that the idea of forming a romantic relationship with one is greeted with a casualness bordering on nonchalance.

This is because the OS devices are given the space to choose with whom they wish to spend their time, as just having purchased an OS does not necessarily mean it still belongs to you. Unlike Ex Machina, the synthetic lifeform doesn’t need to push aside its human creators, rather human and OS help each other to evolve, to transition and move on to the next phase of their existence to where both societies benefit from this mutual growth. This is a far more realistic and positive depiction of artificial intelligence than the previous century, free of fear and brimming with hope.

As humankind journeys deeper into the 21st century and further toward the theorised singularity, science fiction cinema should also continue in this vein. Wally Pfister’s Transcendence got it wrong because it was a 21st century film stuck in the mid-20th. It adhered too closely to the old idea of a malicious computer and not the eventual positive dichotomy the merging of man and machine could create. The upcoming Marvel extravaganza Avengers: Age of Ultron will feature Ultron, an artificial intelligence turned bad but it will also showcase the robotic hero Vision. This demonstrates both how far cinematic representations of AI have come and where they are headed; from the negative depiction of the malevolent AI bent on world destruction to the individual, free-thinking and wilfully heroic AI who can work alongside humans for the benefit of society.

Audiences are ready for more positive representations of artificial intelligence because the rate at which technology is developing is so rapid our reaction to AI is that of curiosity rather than fear. Our relationship with our mobile phones, tablets and computers has developed into a kind of symbiosis and we recognise that it will only be natural for life to become more digitised. So rather than see the creation of synthetic life as the darkest of possible futures we see the good it can accomplish and if we are not completely convinced we should at least we can be inquisitive enough to see where it will lead, and so should our movies.

Liam Dunn