It’s a half-hearted pun that many have made since last August, when the title and basic premise of Nolan’s latest film was first announced. With a November release date set, and only the most teasing of teaser trailers put forward, little is known of the project beyond its startlingly starry cast. Anticipation couldn’t be more feverish, an indicator just how much the English filmmaker has grown in the 14 years since Memento, his first cinematic effort and instant classic. In many ways, he has replaced the listless Ridley Scott as one of the movie business’ most exciting exponents, his every release dripping in not just hype but substantial promise.

He may have lost essential and trusted cinematographer Wally Pfister, who has enjoyed Transcendence into the realms of directing himself (another half hearted word play), but this has not diminished Nolan as a force. The sheer, unbridled financial dividends of his Batman reboot and Inception, on top of the critical acclaim of Memento and The Dark Knight, has given him carte blanche. This is not a result of cynical market playing, however. Nolan has earned his keep by dint of not just vision and execution but depth. He always buries material under the surface and always strives for something more than a simple genre piece.

Nolan is by no means a flawless filmmaker, but is certainly an intelligent one and a writer/director who is inspired by ideas. Don’t worry yourself about the social implications of holding up a superhero movie as art house. Simply look further, discover the double life led by each of his films and introduce yourself to a master story teller; a story teller who, through achieving one straightforward goal, has achieved many others that many haven’t noticed. Are you watching closely?

The mind bending noir riddle that is his first film, Following, invariably set the tone both for Nolan himself and his prospective audience. It further emphasizes the importance of a filmmaker’s origins, that low budget outing providing an utterly indispensable final exam before graduating with honors into the cinematic fold. When it came to this advancement, Nolan hit the ground running with a 2000 film that many still consider his best work. Memento, another noir thriller with another mind bending twist in the tail, hailed as a masterpiece and at the time marking its director as a future star.

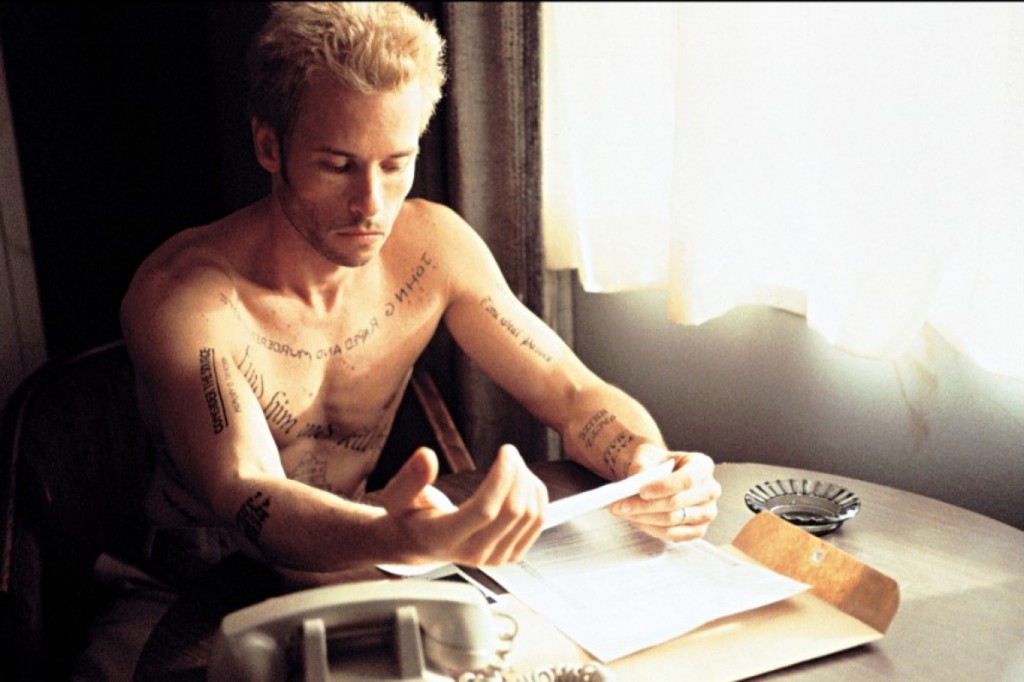

Re-watching Memento is essential for numerous reasons. The first viewing is always a stark one, the chronologically reversed structure not allowing a moment’s rest as the audience wrestles with the layout of the plot. Notes are taken, memories of past interactions triggered by revelation. During an era when mystery thriller was no longer considered sufficient and plot twists became the norm, Memento seemed to simply be the best of the crop. A second helping was required for one not only to clear up all the mysteries and answer the outstanding questions, but to get a real sense of what they had seen. After two viewings, you understand and see the full picture. This is the surface, however, a Polaroid finally coming into focus. Keep looking.

Viewing Memento again reveals that this is not a gimmick. The structure is in fact an ingenious perspective to best articulate Leonard Shelby’s unique medical condition, his inability to create new memories represented by the audience’s ignorance. We follow him on this journey by the same path, continuously finding ourselves on stepping stones with no idea how we got there. Nothing seems familiar. We have to wait to find out how this path forms up. It is the ultimate immersive experience. Don’t stop there, keep watching. Yet another viewing reveals that this is not just a tight, taut thriller, but a philosophical enterprise exploring the importance of memory when defining self. What are we without our memories? What is life, what is its meaning, when we do not even know what we have just done? How can one build a bearable existence when we no longer know who we are? And, most importantly, how can we heal when time loses all meaning?

This is the most important question it raises, because watching yet again, breaching yet another layer in this puzzle box, reveals Memento’s emotional heart, and it is a powerful and melancholy experience. Compelled by the understated but vital central performance from Guy Pearce – the first example of Nolan’s apt hand at casting – the fifth viewing gives us an almost unbearably sad window into the true power of grief. Each Nolan flick carries an overhanging emotion, and loss defines Memento, shapes it and gives it substance. Lenny may be a serial killer by choice, continuously deceiving himself at the expense of his morals in order to find purpose, but he is a broken and defeated man cast constantly vulnerable and truly alone in the world. Forget the reverse storytelling and noir shades and you find rather simple core intent; what grief will drive a person to do. For the first time, Memento draws a tear.

This is the most important question it raises, because watching yet again, breaching yet another layer in this puzzle box, reveals Memento’s emotional heart, and it is a powerful and melancholy experience. Compelled by the understated but vital central performance from Guy Pearce – the first example of Nolan’s apt hand at casting – the fifth viewing gives us an almost unbearably sad window into the true power of grief. Each Nolan flick carries an overhanging emotion, and loss defines Memento, shapes it and gives it substance. Lenny may be a serial killer by choice, continuously deceiving himself at the expense of his morals in order to find purpose, but he is a broken and defeated man cast constantly vulnerable and truly alone in the world. Forget the reverse storytelling and noir shades and you find rather simple core intent; what grief will drive a person to do. For the first time, Memento draws a tear.

Following up on such a masterful display was always going to be a tall order, and it was perhaps inevitable that Nolan’s remake of Erik Skjoldbjaerg’s Insomnia would disappoint. It is a solid effort, another thriller with a twist, but doesn’t match up to the impact of the original and doesn’t come close to Memento in terms of innovation, drama or depth. Hamstrung by his lack of control over the screenplay or source material (Memento was his own screenplay, based on brother and collaborator Jonathan ‘Jonah’ Nolan’s short story Memento Mori) there is a lack of trademark nous and a more formulaic style. Despite this, there is still the overpowering theme. Where in Memento it was grief, in Insomnia it is guilt that swallows up the protagonist. Another understated lead turn (by Al Pacino) and some intelligent use of visual metaphor drives home this point. Rather than hamper his progress, Insomnia’s relative lack of success (though it was still regarded well in critical circles) provided Nolan with the hiccup great filmmakers require to grow further. And it did not prevent him from the next step, one that would signal his elevation to the next level.

The choice of Nolan as the man to resurrect the Batman franchise was a huge gamble. Untested in the field of epic cinema, he was asked to breathe new life into a beloved franchise on the strength of more modest fare, presumably with the hope that he would replace the grandiose with the thoughtful. It is hard to understate the impact this decision had on the future of the superhero subgenre. Action would be supplemented by emotion, character development superseding spectacle. 2005’s Batman Begins, a bold step into a realm not explored by the Caped Crusader outside the realms of his comic book progeny, was the making of Nolan and the game changer that sparked a new era for both DC and Marvel.

Looking back at the first in the trilogy reveals Nolan’s own intentions. Clearly not interested in the cash cow flipside to Batman’s notoriety, he constructed a film without an attached toy line that often sacrifices ‘awesome’ in favor of catharsis. His film is an origins story first and foremost, and though contains big action and suspense and gadgets and duels is not distracted from its true goal; to get inside the mind of Bruce Wayne. The task undertaken by Nolan is how to best look at a man who willingly wears the cowl and the bat ears and spends his nights assaulting the criminals of Gotham City. The film is a deconstruction of a character who has become a legend since his inception in 1939, opening him up for analysis, treating him as a breathing, living soul. Begins is a very simple character piece, exploratory surgery on the man behind the mask. This is not, as we see, simply a hero; he is as defined by darkness as heroism. Remove the vigilante crime fighting, multi-million dollar arsenal of weapons and plots to exterminate Gotham and it is just a story of a troubled man overcoming his demons and fears and finding his place in the world.

In many ways, you could argue that Nolan took this on without taking any real interest in Batman himself, rather using the brand as a means to an end. Offered a project that would make him one of the film industry’s most trusted and powerful figures, he chose to approach the Bat not in a way that would sell the most tickets but in a manner that he himself could find an interest in. This is perhaps most glaring in his sequel to Begins. If the origin story had changed the game for superhero movies, 2008’s The Dark Knight changed the landscape on which they would be judged.

In many ways, you could argue that Nolan took this on without taking any real interest in Batman himself, rather using the brand as a means to an end. Offered a project that would make him one of the film industry’s most trusted and powerful figures, he chose to approach the Bat not in a way that would sell the most tickets but in a manner that he himself could find an interest in. This is perhaps most glaring in his sequel to Begins. If the origin story had changed the game for superhero movies, 2008’s The Dark Knight changed the landscape on which they would be judged.

Standards rose like dreamscape skyscrapers. It was touted as being the first comic book movie that could potentially receive Best Picture recognition at the Academy Awards, and for a time stood at the summit of IMDb’s controversial film chart. Though it didn’t gain that nod or stay at the top of the list, Heath Ledger’s posthumous Oscar and an astonishing box office return did enough. This turnout is more notable when you consider that Nolan, again, wasn’t making a Batman movie. The sheer ambition of Nolan is laid bare with The Dark Knight. Approaching a desired sequel to the warmly received Begins, he was forced to find a new angle through which to approach material that, while not alien to him, did not mesh easily with his sensibilities. The result was uncannily suitable – he chose to make the film he had always wanted to, the crime thriller. Inspired by Michael Mann’s Heat as much as Bob Kane, Nolan set about creating a story grand in scale as a vigilante, politician and police officer attempted to bring down a criminal mastermind tearing their city apart.

Once again, the cowl was a means to an end, an entry point to access a story less about the bat than the game he played. Naturally, thematic resonance was key. But although many stipulated that ‘chaos’ was the overarching idea behind TDK, a much more powerful thread of thinking is the examination of one’s limits. It explores just what a man must become to stop evil, whether a hero can truly be a hero and survive. Harvey Dent’s infamous line on the matter may be foreshadowing, but also reveals the idea that becomes the film’s crux. At what cost does one become a true hero? How can you protect what you love, defeat monsters, without becoming a monster yourself? Chaos, like Batman, is a tool. Ideas defining the picture.

Just as The Dark Knight allowed Nolan to make his own genre piece, its sequel The Dark Knight Rises provided another opportunity to remold the material to his own tastes. Rises, though a perfect conclusion to the saga, is another departure from the hero’s apocrypha. With material such as A Tale of Two Cities tickling his ambitions and the films of David Lean providing inspiration, Nolan directed Rises as his own film epic. Huge set pieces, apocalyptic destruction, society’s collapse and the desolation of a man’s soul. It is the stuff of far flung ambition, normally confined to the limitless niche of literature, yet it exists in the annals of Batman lore now. Rarely has a film ever been so mouthwatering, so hyped beyond recognition. And, most crucially, seldom has Nolan ever been so powerful with the emotional punch.

Just as The Dark Knight allowed Nolan to make his own genre piece, its sequel The Dark Knight Rises provided another opportunity to remold the material to his own tastes. Rises, though a perfect conclusion to the saga, is another departure from the hero’s apocrypha. With material such as A Tale of Two Cities tickling his ambitions and the films of David Lean providing inspiration, Nolan directed Rises as his own film epic. Huge set pieces, apocalyptic destruction, society’s collapse and the desolation of a man’s soul. It is the stuff of far flung ambition, normally confined to the limitless niche of literature, yet it exists in the annals of Batman lore now. Rarely has a film ever been so mouthwatering, so hyped beyond recognition. And, most crucially, seldom has Nolan ever been so powerful with the emotional punch.

Each part of the trilogy represents a step taken by Bruce Wayne, his fractured and vulnerable protagonist driven by unthinkable forces of will, and Rises is his nadir. Broken; devastated; defeated. As already mentioned in a prior article, the film is as much about overcoming depression as it is defeating the League of Shadows, and allied to the scope of the story this makes for moviemaking that is vast not just in spectacle but in soul baring heft. The theme is not revenge or redemption, nothing so large. It is simply pain, and the manner in which we use it to defeat it. It worked; the film became a behemoth at the box office and was universally acclaimed.

Thus concluded the saga. It is a remarkable achievement that Nolan created one of cinema’s most beloved and immortal trilogies, changed the landscape for the sub-genre and not just vindicated but built upon the legend that is Batman…all while never making a Batman movie.

Prestige, Inception, and the Magic of Meta

Prestige, Inception, and the Magic of Meta

Indeed, he was not only taking the chance to make the films he aspired to while serving as Bat watchman, but doing something to earn something. Rises has allowed Nolan to make Interstellar, just as Batman Begins allowed him to make The Prestige and The Dark Knight granted him Inception. The Prestige saw Nolan again tap into pre-established source material, namely Christopher Priest’s novel, while 2010’s Inception proved to be his first foray into entirely original waters since Following. Both films share a great deal, not just in terms of how they came about or how they indulge in a little sci-fi to tell their respective tales, but in the manner the stories are told. Most notably, both are astonishingly meta.

It is not an original notion to suggest that Inception isn’t really about dreams and espionage but rather about filmmaking itself. Many theses and essays makes this point. It is clear that although there is a clearly defined heart to the film, a theme of letting go and moving on after tragedy in an evolutionary growth on Memento’s posit, it is really showing the process a director and his crew go through to satisfy its audience. Cobb is that director, Fischer is the audience, and so on. What is a little less well-worn is that Inception is the spiritual successor to The Prestige, which operates along the same lines but with a differing point.

If Inception took Memento’s themes and moved them onto something approaching closure, The Prestige takes the same ideas and mutates them into even darker shades. Once again, we have revenge as purpose, but also obsession as driving force, and a stark look at the emptiness and unhappiness that comes with such a dark quest. When these characters feel they have nothing else to gain from life but their ferocious personal battle, they inevitably up the ante so highly that nobody can ever get near redemption. It is Inception’s evil twin, as full of wonder and amazement but without the warmth that comes from a last minute escape into happiness. It also takes the same tack regarding cinema.

Inception took the idea that a filmmaker must implant an emotion in its audience, and that everything else from the action to the scenery is built around it to create an immersive experience. The viewer will come away with a feeling that seems unique, like they alone enjoy it, but in truth, it was placed there by the director. The Prestige goes for another angle: a full-scale deconstruction of the plot twist. The three steps to a great trick, as outlined by Nolan stalwart Michael Caine, applies not to the magicians of the plot but to the makers of the movie we are watching. The pledge is the film’s premise. The turn is a shocking turn of events that alters the narrative and makes the audience gasp. The prestige is the revelation of the twist, truth seen at last, that will justify the trick pulled. We see both Borden and Angier carry out their Transported Man tricks and cannot understand how.

Inception took the idea that a filmmaker must implant an emotion in its audience, and that everything else from the action to the scenery is built around it to create an immersive experience. The viewer will come away with a feeling that seems unique, like they alone enjoy it, but in truth, it was placed there by the director. The Prestige goes for another angle: a full-scale deconstruction of the plot twist. The three steps to a great trick, as outlined by Nolan stalwart Michael Caine, applies not to the magicians of the plot but to the makers of the movie we are watching. The pledge is the film’s premise. The turn is a shocking turn of events that alters the narrative and makes the audience gasp. The prestige is the revelation of the twist, truth seen at last, that will justify the trick pulled. We see both Borden and Angier carry out their Transported Man tricks and cannot understand how.

We know it defies logic. But the sheer shock of it is not sufficient, as Caine’s Cutter states. We need a pay-off, to see how it occurred. The prestige is in learning that Borden is actually identical twins and that Angier’s machine creates copies of himself. Two earth-shattering twists in the space of a taut final 5 minutes. With this, the film effectively explains its own machinations while they occur. Both feats are somehow incredibly simplistic – just as an author writes about writers – yet mightily ambitious. They threaten to derail the movie by making it too self-referential. But they are hidden well, thinly enough to be recognizable but heavily enough not to make themselves blatant. Both unveil the core strengths of Nolan as a filmmaker, in his emotional focus and his penchant for the game changer, and reveal how he achieves this. It is the apex of idea-led filmmaking, yet is clothed in two supremely dressed, superbly executed and thematically resonant pieces. Like every film he has ever made, Nolan works in threes. Consider the evidence one last time, namely what each of his films presents:

Memento – Noir thriller – immersive gimmick structure – tragic story of grief.

Insomnia – Murder mystery – empathetic metaphor setting – the torture of guilt.

Batman Begins – Superhero action movie – redemption story – defeating fears and trauma.

The Prestige – Mystery thriller – 4th wall breaking meta – the evils of revenge.

The Dark Knight – Superhero action movie – epic crime story – exploration of one’s limits.

Inception – Sci-fi caper – further meta filmmaking metaphor – finding closure and release.

The Dark Knight Rises – Superhero action movie – classic epic movie – overcoming loss.

Not including Following, Nolan has made seven movies, but through them has told 21 different stories, all tightly packaged in films that cannot be described as anything inferior to solid. With Batman and Inception, he concocted blockbusters that could rival or top those of maestros such as James Cameron. In Memento and The Prestige, he told florid and complex tales of immorality and suspenseful thrills. But at the same time, he has consistently spun emotional and ideological fables that challenge the mind and graze the heart. And, deeper still, there is another story, one that molds all around it. The prestige.

It is this, and not box office revenue, that confirms Christopher Nolan as one of cinema’s brightest lights and most essential voices. That he can reach and touch so many of such differing tastes while never compromising his ideas is astonishing. For this reason, his films will always be hyped, always be tantalizing as they approach. So we plough on to November for the next step in this voyage.

As we go with him, go Interstellar.

— Scott Patterson