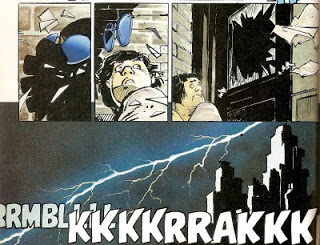

This hardly feels like pages ripped from a William Gibson novel, more like frames from a grainy, 35-mm Taxi Driver print. The synopsis for TDKR returns dubs itself “near-future”, and the genre “cyber-punk” has been tossed around by readers and critics alike. But really (mutant punks aside) the book falls into the Death Wish genre. Aging man, urban and moral decay, vengeance, redemption. These are common themes in Miller’s work. His heroes – battered, beaten, bruised – seek to righten the world around them through brutal means, their loved ones often murdered or worse. In Frank Miller-world, going out at night alone is definitely not a good idea.

Miller’s first decade in the business was undoubtedly his best. He filled in on Daredevil as artist in 1979. His dramatic skylines and shadowing changed the look of the book. However, sales didn’t budge and Marvel contemplated canceling the title. It wasn’t until Denny O’Neil was brought in as editor that he fired the previous guy (shall remain nameless) and hired Miller as full time writer and artist. By ’81 sales on Daredevil were up, and Miller stood on the front lines of pushing mainstream superhero comics into exciting new territory. The decade featured his classics (that my esteemed Sound On Sight colleagues are elaborating on): his work with Chris Claremont on Wolverine, Daredevil Born Again, Ronin, the aforementioned The Dark Knight Returns, and finally the defining Batman: Year One. The latter debuted in 1987, marking the end of the Miller’s initial era in comics.

Many would say that Miller’s descent into self-parody begins in 2000 with the critical (and eventual commercial) failure The Dark Knight Strikes Again and especially with his shiver-inducing run on All-Star Batman with Jim Lee. His characters had become even more mean spirited and lost any small traces of heart they once had. His drawing went from stylistic Expressionism to something else entirely… a poor excuse for surrealism. Both his writing and art went from dramatic to way over-the-top, often times laughable. I would argue there are shades of this in his 1990’s work as well; that his slow descent into self parody begins with his return to comics at publisher Dark Horse in 1991 (post-Give Me Liberty, an almost un-Miller Frank Miller book), after his failed scripting attempts on the Robocop sequels. His decline might have less to do with him, and more to do with his surroundings.

Many would say that Miller’s descent into self-parody begins in 2000 with the critical (and eventual commercial) failure The Dark Knight Strikes Again and especially with his shiver-inducing run on All-Star Batman with Jim Lee. His characters had become even more mean spirited and lost any small traces of heart they once had. His drawing went from stylistic Expressionism to something else entirely… a poor excuse for surrealism. Both his writing and art went from dramatic to way over-the-top, often times laughable. I would argue there are shades of this in his 1990’s work as well; that his slow descent into self parody begins with his return to comics at publisher Dark Horse in 1991 (post-Give Me Liberty, an almost un-Miller Frank Miller book), after his failed scripting attempts on the Robocop sequels. His decline might have less to do with him, and more to do with his surroundings.

What often goes unsaid about Frank Miller’s entrance into comics in the late 70’s/early 80’s is that he wasn’t alone. He was part of a larger movement of creators who brought street level realism to comics throughout the 70’s, many of whom lived in New York. This movement arguably begins with Gerry Conway — a then resident of a decaying NYC — deciding to drop Gwen Stacy off the Brooklyn Bridge in the pages of The Amazing Spider-man in 1973. The consequences had become real, this was life and death. Hell, it even says on the front of ASM #121, “Turning Point”… and it was for the industry.

These changes in comics weren’t objective to the reality of a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam United States. Comics, as all art, are subject to the environments around them. Consciously or subconsciously. And the 60’s were over, man. With them the idealism of social change and the freedom from the establishment had faded. There was no escape through hallucinogenics and free love. Economically, socially, and morally the United States seemed to not only be stuck in a rut, but on a downward plunge where the bottom never seemed to actually hit. New York City sat in the center of it all, the 1970’s would become notorious as the city’s worst decade. Crime and poverty peaked, infrastructure crumbled. Corruption took root in the NYPD and state/city officials. There was a 25 hour blackout in ’77, resulting in racially charged destruction of property and looting with over three thousand arrests. The decaying of the greatest city in the world made vigilantes out of some, like the real-life Bernie Goetz (Google him) or the fictional Travis Bickle.

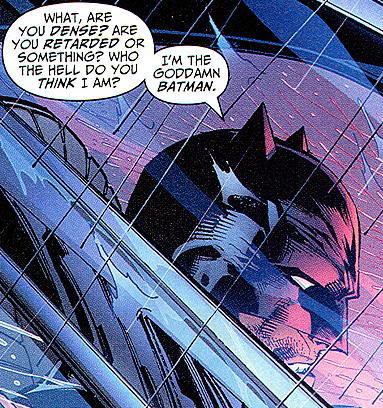

Miller grew up in rural Maryland. A baby boomer, one of seven children, his family was Irish Catholic. Things like The 300 Spartans, “hard-boiled” detective fiction (elementary understanding?), and the writings of Ayn Rand peaked his interest. Explains quite a bit, right? As a teen the Millerisms were already setting in; he used his high school newspaper to point out the “moral failings” of his teachers. It’s as if ever since he was born, every event in his life was leading him to write the “I’m the goddamn Batman” diatribe and think it’s a good piece of dialogue.

The path to righteousness didn’t stop at high school. Miller packed up his portfolio of drawings and shoved off for New York City in the mid-70’s. Wide eyed and perhaps a little naïve to begin with, it didn’t long for those Ayn Rand worldviews to be validated in the heat of the big city. After seeing his art rejected repeatedly, he had to take a job doing carpentry work for a stranger out of desperation. Now, I’m not sure how much of what follows is cold-hard truth and how much is cooked up fiction… but turns out the guy he worked for was a dealer. Not only that, but a dealer wanted by the local Mafia. He walked into work one morning and there were men with guns pointed at him; they knocked him out and he woke up blocks away. One month, he was robbed on three separate occasions. Miller had already started writing some when he and his then girlfriend decided the everyday threat of violence was too much: they shipped off for L.A. It didn’t stop there, though. Someone tried to rob him again on the sunny streets of Los Angeles.

Which is precisely why Miller’s early stuff feels so much more raw and honest than his latter-day work: the experiences were fresh, the emotions burning hot. His first era had the authenticity of someone living knee deep in those stark, shadowed cityscapes. Batman and Daredevil were Bernie Goetz. Imagine Frank, after one of his many dealings with the filth of the city, glancing up at the rooftops, imagining the superhero of the early-40’s stalking the rooftops and serving fistfuls of justice to his wrong doers. This also explains why his post-90’s work (certainly his 2000’s work) seems so damn… off. There’s something inherently wrong with it; even those who enjoy reading those stories sense it. It isn’t so much dishonesty as a lack of adaptation.

Frank Miller – wherever he resides in 2014 – thinks he’s still living in the squalor of 1978 New York… at least that’s what his art screams. Somewhat ironic, considering the two non-creator owned characters he hit out of the park are masters of adaptation. The further time (New York specifically, which as you know has dramatically improved since those times. Stop and frisk aside.) pushes away from that era, the further Miller’s work strays from reality. His Daredevil run felt urgent and timely; Sin City started to feel distant, somewhat detached; and finally All-Star Batman & Robin felt so cold and completely isolated from reality that its “street-level realism” felt like an outright lie at best, and at worst the very dredge of what comics have to offer. His oft-mocked “wake up, pondscum” rant against the Occupy Wall St. movement might serve as the perfect Mad-Libs style template to send back his way. Swap out some nouns and verbs and all of a sudden you’ve got a perfect letter to Miller:

Everybody’s been too damn polite about this nonsense:

Everybody’s been too damn polite about this nonsense:

The “Frank Miller” movement, whether displaying itself on the silver screen or in the pages of DC (which has, with unspeakable shock, tolerated it) is anything but an exercise of our blessed First Amendment. Frank Miller characters have become nothing but a pack of louts, thieves, and rapists, an unruly mob, fed by Atlas Shrugged-era nostalgia and putrid false righteousness. These ideologues can do nothing but harm comics.

“All-Star Batman & Robin” is nothing short of a clumsy, poorly-expressed attempt at characterization, to the extent that the “characters” – HAH! Some “characters”, except if the word “false” is attached – is anything more than an ugly fashion statement by a cowboy hat wearing, crabby old coot that should stop getting in his own way and just retire already.

This is no soulful uprising. This is garbage. And goodness knows he’s spewing his garbage – both politically and artistically – every which way he can find.

I don’t need to continue, you finish the rest. Look, the guy has written some of the most iconic comics of all time. Most… no, all of which were created early in his career. As The United States entered the 1990’s (the Cold War ends, economic mobility and moral turpitude returns in certain capacities, Giuliani cleans NYC streets) Frank Miller’s writing was already becoming dated and fake. Again, I do empathize with his story, but there comes a time where you need to move on with your life, your philosophies, and your art. Or, ya know, don’t and become the crazy old great-uncle you don’t even get mad at anymore, you just roll your eyes and ignore everything he says.