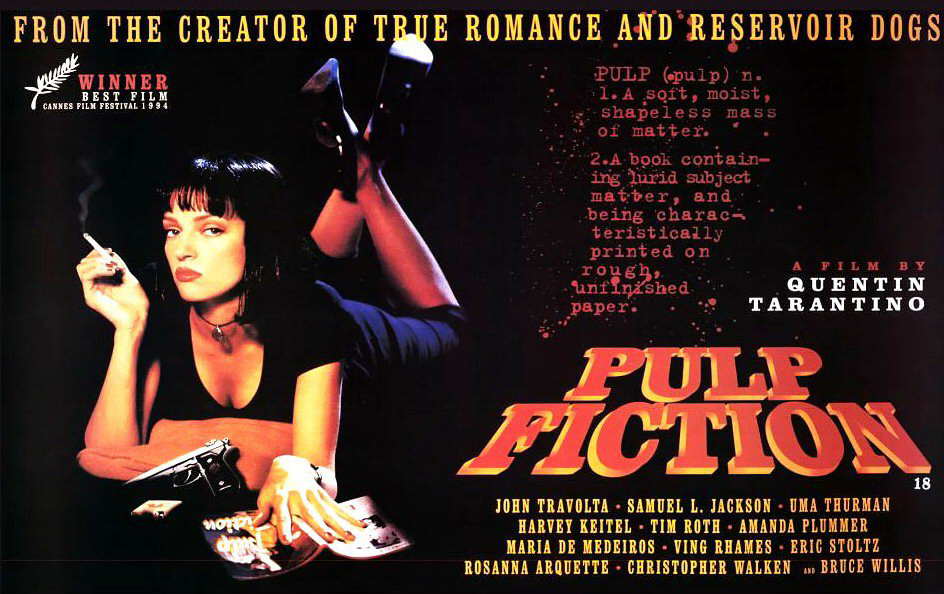

Measured against the guidelines for creating good drama as articulated by Aristotle in his Poetics a few millennia ago – the earliest surviving treatise on literary theory — many of the big-budget studio releases of the last 20-30 years stand pretty feebly. While some might understandably wonder whether anything anybody wrote about good stage drama nearly 2400 years ago has any relevancy to movies today, Michael Tierno, a one-time story analyst for Miramax Pictures, says – firmly — yes. Taking it a step further, Tierno maintains the Greek philosopher’s tenets of dramaturgy have held first playwrights, then screen scenarists and TV writers, in good stead for centuries. He set that credo down in his book, Aristotle’s Poetics for Screenwriters: Storytelling Secrets from the Greatest Mind in Western Civilization (Hyperion, 2002), applying the ancient Greek’s primordial how-to concepts to such contemporary fare as The Godfather (1972), Rocky (1976), and even the hyperkinetic, chronological juggling act of Pulp Fiction (1994).

Tierno’s assessment of so much of what is on-screen today is that the typical big-budget action-fest elevates to the fore the element of dramatic storytelling Aristotle considered to be “…the least  important”: spectacle. The Greek philosopher divided drama into six component parts. Most important of them were:

important”: spectacle. The Greek philosopher divided drama into six component parts. Most important of them were:

Plot

Character

Character thought

Dialogue

Those elements Aristotle considered least important were:

Music

Spectacle

The Aristotelian concept of spectacle in drama is different from what we think of in using the word today. Aristotle did not mean epic scope or eye-dazzling production values. By spectacle, he meant the substance of the medium itself; elements Tierno identifies in films as cinematography, editing, production design, and the other physical makings. His interpretation of Aristotle’s prioritizing of spectacle is that the dramatic storyteller not become so steeped in the mechanism that he/she forgets the human dynamic of the story. “But that’s what film schools emphasize,” he says. “Tell the story visually, they keep saying, so these young filmmakers ignore things like dialogue and character.”

Tierno speaks with a table-banging passion about the necessity of character, and how little of what passes for such in modern-day thrillers really is character. “Character is not this contemporary idea of funny quirks and traits,” he says. “Character is the moral choices that reveal who the character is.” He refers to the concept of the “mental object,” which might be most easily transposed to the idea of story vs. plot. Plot is generally perceived as the sequence of events we see unfold, while story is something deeper and more abstract; it is very much a part of the drama in front of us without actually being seen.

As an example, Tierno cites the restaurant assassination scene from The Godfather. Al Pacino, playing the son of crime lord Marlon Brando, meets with corrupt police captain Sterling Hayden and ambitious narcotics peddler Al Lettieri, ostensibly to discuss a gang war truce, but actually to kill them both to avenge their attempted murder of his father. The incident is pivotal not just in terms of the plot, but in its impact on the emotional and psychological subtext of the movie. Pacino’s killing of the two men pushes him from his law-abiding arms-length relationship with his father’s occupation into a morally corroding slide which will leave him steeped, by the end of the movie, in self-rationalized evil. “That’s what I mean by a ‘mental object,’” says Tierno. “The mental object of that scene is not just what Michael Corleone is going into that restaurant to do; it’s about what the act will cost him.” This, Tierno explains, is what Aristotle meant by the concept of “character thought”; not what we see, but what we understand to be in the character’s head.

As an example, Tierno cites the restaurant assassination scene from The Godfather. Al Pacino, playing the son of crime lord Marlon Brando, meets with corrupt police captain Sterling Hayden and ambitious narcotics peddler Al Lettieri, ostensibly to discuss a gang war truce, but actually to kill them both to avenge their attempted murder of his father. The incident is pivotal not just in terms of the plot, but in its impact on the emotional and psychological subtext of the movie. Pacino’s killing of the two men pushes him from his law-abiding arms-length relationship with his father’s occupation into a morally corroding slide which will leave him steeped, by the end of the movie, in self-rationalized evil. “That’s what I mean by a ‘mental object,’” says Tierno. “The mental object of that scene is not just what Michael Corleone is going into that restaurant to do; it’s about what the act will cost him.” This, Tierno explains, is what Aristotle meant by the concept of “character thought”; not what we see, but what we understand to be in the character’s head.

If today’s big budget movies come up short on story and character, Tierno fails them equally on the matter of plot, despite their often non-stop action. “Aristotle says that your plot should be so strong that if you relate it to somebody, they should be as moved as if they had actually seen it.” In a world of 15-minute pitch meetings and 30-second TV promotional spots, the opportunity to develop those kinds of plots are rare at the major studio level. He sees the current studio mentality as being, “We’re gonna spend a lotta money to make a lotta money” i.e. spectacle. And, unfortunately for Aristotle and his aesthetic disciples, audiences for these kinds of films “…interpret that expenditure as value.”

Tierno, whose own passion found its put-up-or-shut-up moment in writing and directing his self-financed feature, Auditions (1999), looks at what pours into multiplexes each summer and shakes his head. “You need to make the film you want to see. Trying to guess what the audience wants produces empty films. There is no soul there.”