Written and directed by Dave McKean

UK, 2014

While Mirrormask has become something of a cult movie, Dave McKean is still better known for his work in illustration than his directorial efforts in film. McKean’s groundbreaking style consistently raised the bar in comic art; his contribution to the 1989 release of Arkham Asylum, written by Grant Morrison, helped change our understanding of the artform. McKean’s style seemed uniquely suited to the mind space of an asylum, his layered mixed media style reflective of thoughts and emotions in conflict. Perhaps his best known work is his contributions to the cover art for Neil Gaiman’s iconic Sandman series, once again cementing the phantasmagoric quality of McKean’s work. His collaboration with Gaiman highlighted the obscured landscape of nightmares which he frightfully recreated through superimposition, collage and drawing.

It should be no surprise that McKean’s transition into filmmaking maintains a psychological point of view. This new medium reflects different demands, and the style of Luna blends different film stocks, animation, superimposition and a jarring structure in its exploration of grief. Set in a remote cottage by the sea, a group of friends are reunited for the first time in many years. Much has changed over time: first we have Dean (Michael Maloney), who has divorced his wife and remarried a much younger woman, Fraya (Stephanie Leonidas). On the other hand there is the short-tempered Grant (Ben Daniels), who is married to Christine (Dervla Kirwan); they are still recovering from the unexplained death of their newborn child. Grief and regret hangs heavy over the intimate proceedings of the film, as people dance around their true feelings and repress their anxieties. It is through the psychological space that McKean creates through his animated and surreal sequences where the characters are finally able to confront truth.

Nothing is easy about the reality that McKean creates; his characterizations feel familiar, intimate and real. The performances are rich and engaging, with the actors bringing with them a wealth of experiences, dreams and desires that exist far beyond the confines of the screen. As the group of friends reunite, we get an eerie sense of an Edward Albee teledrama: insinuations are made, issues are danced around, and no one says what they mean. McKean undercuts this discomfort through a strange musical interlude that overlays the conversation, a stylistic choice that is jarring but somehow successful in its earnestness. What the characters are saying is irrelevant, they are talking at each other about nothing — they are just filling the dead air.

As the narrative develops, the characters’ interior world begin to unravel. It becomes clear that while Christine and Grant have been picking up the pieces of their life, this visit to the sea has begun to undo much of their hard work. The sea always has associations with renewal and the origin of life; it is a familiar mythological symbol and here it washes to the surface the horrors that the characters have long been hiding from. Their dreams become darker and reality loses its certainty. While this offers a certain amount of relief, some of the fantasies feature a wandering nymph child who renews hope in life, while others like an imprisoned monster suggest the hopelessness of survival.

The strength of Luna‘s surreal imagery is that it maintains a certain level of ambiguity without being overly dense. We can tie them to feelings, events and themes, but they are never so overt that the audience feels guided by the hand. In the same way our own dreams remain a mystery to ourselves, so do these dreams maintain that air of the unknown.

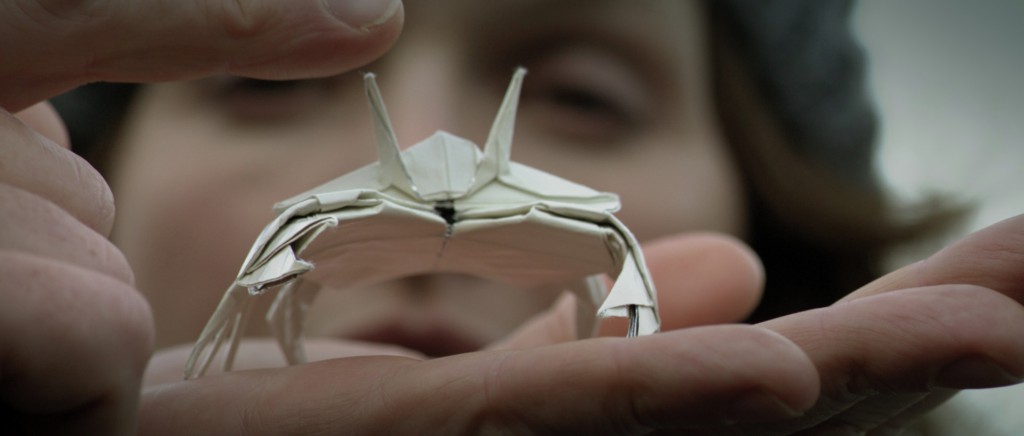

Two of the protagonists are artists: one never wants children but spends his life illustrating children’s books, while the other — the father who lost a child — can no longer draw, because all his creations inevitably reveal the thoughts that he is hiding from. Every work he creates is a mirror of his lost child; he abandons art because the world of his subconscious is more real than his waking days. The film posits a very real take on the artistic process, and beautifully relates the struggle of artistic creation to parenthood. For Grant, drawing is too close to fatherhood; it is a reminder that he is a father who lost a son.

In many ways, Luna adopts a wholly original structure. It defies normal pacing that we have come to associate with traditional narrative filmmaking. This is occasionally jarring, in particular early on when we have not adjusted to McKean’s vision. Some of the film’s jump cuts in particular feel somewhat ill-placed, but they can often be forgiven as the film’s editing style seems dictated more by emotion than it is traditional forms. The editing rules the transitions between reality and dream, though, in particular evoking a sense of literally crossing a threshold between conscious and unconscious. It is difficult not to think of both Joseph Campbell and, by association, Neil Gaiman in how this is handled. Campbell outlined very clearly in the “Hero’s Journey” that the moment in which the character sets off into his journey sees him crossing the threshold into the unconscious. This idea becomes absolutely crucial in Gaiman’s Sandman series, which playfully toys with the concept. While in Luna the barrier between waking and dream is usually defined, we understand that consciousness and unconsciousness are not mutually exclusive, but rather states of being that run parallel.

Luna is, without a doubt, one of the most evocative cinematic works of the year. It is refreshingly original in both narrative and form, offering a hard-hitting exploration of grief. The film utilizes storytelling traditions that incorporate symbolism and mythology in order to explore the pitfalls of growing older and finally taking responsibility. The fantasy is neither easy nor whimsical and brings you on a journey through the subconscious world where you cannot escape what you’re hiding from.

–- Justine Smith

Visit the official website of the Toronto International Film Festival.