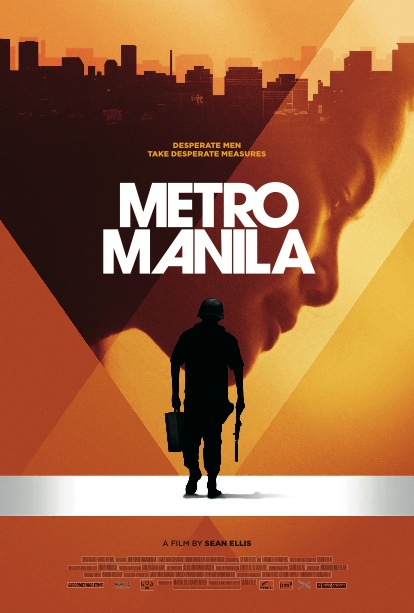

Metro Manila

Written by Sean Ellis & Frank E. Flowers

Directed by Sean Ellis

UK/Philipines, 2013

Manila has the highest population density on the planet. Per square mile there are 111,002 people; by comparison my home of Chicago is only 11,868. While many economists look at the Phillipines as an marketon the rise, the disparity in wealth is the worst in Asia, with the richest families accounting for over 50% of the country’s total family income while the poorest account for less than 5%. In Manila, the rich live in gated communities while the poor live in slums, squatting on abandoned government-owned land. It’s important to know these facts when approaching Sean Ellis’ Metro Manila, because the city plays such a large role in determining the destiny of its characters.

Oscar Ramirez (Jake Macapagal) and his wife Mai (Althea Vega) are rice farmers who decide moving to the city will yield better opportunities for themselves and their two young children. Rice isn’t fetching the same price it used to – not even enough to buy seed for the next season – so this plan doesn’t seem like the worst idea, until the Ramirezes get there and are swindled out of their savings and find themselves homeless and starving. Through chance, Oscar finds himself as a guard for an armored car delivery service; his wife becomes a comfort girl at a seedy bar that lets her kids sleep in the dressing room. At no point does Oscar admonish his wife for having to do what many men in these types of films dread the most, and it’s one of the most telling aspects of the film. This is how desperate these times are, and that their love for each other is about sacrifice – not ownership – and that they must live for each other and for the lives of their children.

Every hand that reaches out to help the Ramirezes, if any, only does so with the intention to exploit them for personal gain, and it’s because of this that Metro Manila can feel as oppressive as its subject matter. Watching Oscar and his family run into nothing but one duplicitous schemer after another can be as overwhelmingly smothering as the city itself, bursting with people on top of people on top of people. While it’s necessary for the film to bear down on these characters to see how strong their wills hold up, it sometimes borders on contrivance with a reliance on some of the “greatest hits” of immigrant exploitation films of the past. However, it doesn’t seem as though this movie is trying to present this particular story – with tropes found in a sub-genre that includes films like this year’s The Immigrant and Stephen Frears’ Dirty Pretty Things(2002) – as something new. The story remains the same, only the location has changed. Metro Manila is at once foreign and even exotic, but it’s heart is identifiable no matter where you reside. Oscar sacrificing his life for a paltry wage to protect other people’s riches and Mai being reduced to using her body to make money isn’t just isolated to Manila – it happens to men and women the world over and has been for very long time.

Sean Ellis isn’t Filipino. A British filmmaker who emerged with his Academy Award nominated short film Cashback(2004), which he turned into a first feature, Ellis had visited the country once, and found himself wanting to make a movie about the people of Manila. What allows an outsider like Ellis to make a film like Metro Manila is the ability to find universal truths in his character’s situation. A speech given by Oscar’s partner Ong (played with honest conviction and desperation by John Arcilla) has him extolling the foolishness of the lottery, but it reveals what he perceives to be the methodology in which people manage to exist in such a harsh word. He tells Oscar that no one really knows any one who has won, but people keep lining up to do it because hope is enough. Ong, however, knows that winning is ultimately impossible. This cynical and fatalistic approach underlies almost every character we run into in Metro Manila, save for the Ramirez family. Ellis’ film posits that this mindset is a product of when the capitalist exploitation of labor meets an overabundance of laborers; laborers who not only recognize that they’re being exploited, but who must in turn take advantage of and oppress each other to succeed. When human value is measured monetarily – in a world where economy dictates survival – it becomes very easy to treat each other as disposable commodities. Metro Manila acknowledges these troubling realities, but still manages to remain hopeful that our sacrifices for the love of others are not in vain.