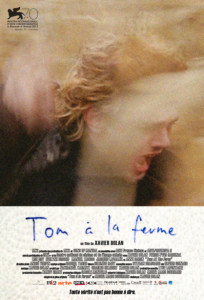

Written and directed by Xavier Dolan

Canada, 2013

Since 2009’s I Killed My Mother, Xavier Dolan has been one of the darlings of Québec cinema. More so than Podz, Éric Canuel, Denis Côté, and rivaled probably only by Denis Villeneuve, the release of a new Dolan film brings with it mouth-watering anticipation. His movies straddle the line between the mainstream and the arthouse, glittering with cool cinematography tricks and crowd-pleasing soundtracks, but anchored by stories and characters not so popular amongst the general public. Each project earns considerable critical reputations, a lustre rarely matched by box office receipts. His latest, Tom at the Farm, despite having the blueprint of a more accessible film, continues his odyssey as an idiosyncratic filmmaker.

Tom (Dolan), a leather-jacket-wearing, bleach-blonde-haired Montrealer, drives to a small town in the provincial country to attend his friend Guillaume’s funeral. He pays his respects by accepting the invitation from the deceased’s mother, Agathe (Lise Roy). to remain a few days at her home on the farm. Unbeknownst to Tom, Guillaume had a brother, Francis (Pierre-Yves Cardinal), a berating, domineering figure who takes a perverse fascination with skinny, demure Tom. When Tom cracks under pressure and opts out of sharing his speech at the ceremony, Frank begins a game of psychological and physical abuse which at first puts the fear of God in Tom, until their aggressor-victim relationship transforms into something far less healthy.

Dolan’s latest is a new example of where the director’s main interests lie. Ever since I Killed My Mother, the writer-director has espoused his lingering fascination with near-destructive relationships involving characters compelled to live through despite threats of instability. His creations continuously want and reject, love and loathe each other. Whereas the slippery slope in his three previous endeavours happened effortlessly and organically, with Tom at the Farm, Dolan must work a little bit harder because the trying bond between his protagonist and Frank is created from almost nothing. The two could not be less compatible, making their pairing Dolan’s tallest challenge yet. It begins in recognizable fashion, following a familiar pattern of the prey shrinking against the iron will of the enforcer. The brute forces Tom to even invent out of thin air a conversation he would have had with the late Guillaume’s girlfriend to appease Agathe, a strange request on face value until it becomes clear that there is more to Frank than meets the eye. The farm boy possesses a strong superiority complex, compelled to control and manage everything quite aggressively. He is also lonely and the only person around to tend to the chores that caring for a farm demands, which partly explains his desire to show Tom the ropes when it is strongly suggested that the latter is gay.

From there, the picture delves into the complexities of Stockholm Syndrome. Granted, the protagonist is not literally a hostage victim but the isolated setting, his moral duty to stay around at Agathe’s request, and Frank’s unflinching presence make it so Tom just might be a prisoner. Frank frequently berates and physically harms his victim (nearly killing him on one occasion), yet the latter slowly comes to accept his lot, even convincing himself that Frank needs his help to keep the farm running at full steam. Whether this is because Tom has masochistic inclinations or because he is tempted by the outside chance that he and his oppressor might consummate what they have is never explicitly laid out, a testament to the nuance Dolan employs to balance the viscera. Make no mistake about it, Dolan’s film is frequently a visceral experience, much of it courtesy of Gabriel Yared’s operatic score, compounding the unnerving energy that drives much of the first half. The director also excels at finding unique visual ways to convey the unbearable tension resulting from the characters’ love-hate relationship, such as compressing the aspect ratio whenever Frank exacts violence on Tom.

The debate is open as to whether or not Dolan is a good actor. Tom at the Farm does not irrefutably confirm his amazing talents or lack thereof. The best way to describe his abilities is functional. He can accomplish the minimal requirements to build a role through performance,but he is the weak link in all three films in which he stars (the exception being Laurence Anyways, which he only directs). On the other hand, Pierre-Yves Cardinal is a force of nature, embodying a twisted version of stereotypical masculinity, showing off brute force while exposing, if awkwardly, his vulnerability and need of companionship, both products of his sad isolation. There are scenes in which Cardinal is absolutely terrifying, while others make the viewer genuinely want to know what makes him tick.

As interesting and well directed as the film is, it does lack a consistent energy to carry the plot through without losing steam. The incredible tempo of his two previous efforts, powerful and irresistible, dissipates in Tom at the Farm’s middle portion. Dolan offers the possibility that the story will head into a different direction with respect to Tom and Frank’s dangerous liaison, testing the bond that has shackled them together for better or worse. Instead, the movie plateaus after a while, suggesting that an abnormally long time has passed (a few weeks at the most, perhaps) with the two figures stuck like glue in the same phase. The arrival of one of Tom’s friends, a calculated risk on his part, livens up the proceedings yet brings the film to a less than satisfying denouement. Dolan seems to know what final shot he wants his project to end on, but is less confident of how to get there.

Tom at the Farm is, in many ways, just as arresting and bold as one might expect. Dolan is, like Québec’s other highly regarded filmmakers, an auteur. Conflicting emotions and styles fuse together to create the attractive cinematic molasses Xavier Dolan has built his still young reputation on. His latest lacks the same level of intense creativity and blistering energy, but until he becomes responsible for a truly dreadful film a new Dolan movie with a few warts warrants a viewing.

-Edgar Chaput