[one_half]

As he has before, Edgar Chaput has inspired me with one of his pieces, this one – part of SOS’s recent Bond Fest — concerning the loopy 1967 Casino Royale. As I commented on Edgar’s piece, I didn’t disagree that Royale was a royal mess after having passed through the hands of one director after another (and one screenwriter after another as well). Mess though it was, however, I found it – as I wrote – a “fascinating mess.” Maybe that’s just a holdover from seeing it as a 12-year-old when so much about the movie seemed so dizzyingly novel at the time: it’s casual sexuality, bawdy humor, wink-to-the-audience jokes, hallucinogenic visuals, Burt Bacharach’s poptastic score. In a way, the fact that the movie didn’t make much sense and caromed from one directorial style to another only added to the sensory overload it unloaded on a pre-adolescent.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

What I take from this is that not all bad movies are equal. Some just stink; others are entrancingly awful.

I remember John Cleese being interviewed by Dick Cavett some years ago, and saying something to the effect that when you understood all that goes into making movies, the surprise isn’t that so few good movies get made; the surprise is that anything gets made at all! There have always been more bad movies than good (I’m not talking about box office flops; plenty of good movies have stiffed, and plenty of turds have minted box office gold). Back in the days of the silents, not every flick which showed up at the neighborhood nickelodeon was a Charlie Chaplin gem. And during Hollywood’s Golden Age, the Casablancas and Gone with the Winds were the rarities. And during that phenomenal creative explosion of the 1960s and 1970s, there was a lot more crud than cream. That being the case, with such an outrageous tonnage of junk, it shouldn’t be a surprise to discover there are all kinds of bad movies.

There is, of course, the standard Hollywood bad; movies that aren’t completely lousy, but just forgettable and disposable. You know; like every other Sandra Bullock movie. Like every Katherine Heigl movie.

And then there are movies that were never supposed to be good. Torture porn, splatter flicks, teen sex comedies. I guarantee you that the cinematic aspirations of the folks behind Saw 3D (2010) were probably less than auspicious.

[/one_half_last]

Some movies are so beautifully, perfectly awful, they have a charm of their own. They become camp classics, as entertaining in their left-handed way (and in a way 180 degrees from what their makers intended) as anything that even remotely passes for good. Think Reefer Madness (1936), Robot Monster (1953), anything by Ed Wood. And just below those are duds that may not be quite as classically bad, but bad enough to be fun bad, Mystery Science Theater 3000 bad (my personal MST fave: Manos: The Hands of Fate [1966]).

But there’s yet another kind of bad, and I’m sure each of us has their pets in this category; the movies we know suck, can even tell you why they suck…yet we keep watching them time and again. Like some sort of slow motion train wreck, we can’t turn away, we remain fascinated. These are our guilty pleasures, the junkiest of the filmic junk food, the cinematic Yodel we keep hidden away to snack on when nobody else is looking, even though we know it’s bad, bad, bad for us.

For me, it’s movies like Casino Royale; the kind of flick where you look at the talent involved, the obvious effort and expense, and wonder, What the hell happened?

I’ve got a couple more…

*****

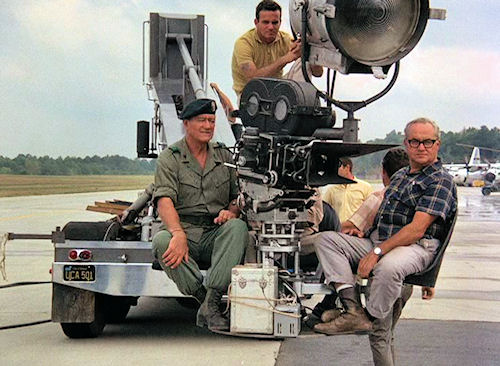

[callout]The Green Berets (1968). Directed by John Wayne. Adapted from Robin Moore’s novel by James Lee Barrett.[/callout]

The Green Berets (1968). Directed by John Wayne. Adapted from Robin Moore’s novel by James Lee Barrett.

Moore did it right. He spent a year training with the Berets, then tagged along with them on a 1963 deployment to South Vietnam. His 1965 book – a somewhat fictionalized version of what he witnessed – was, as I remember, not a political polemic. Though in keeping with the temper of the times it was decidedly anti-communist, the general tone of the book was a straightforward accounting of the dirty ways in which a dirty war was being fought by an elite unit specifically trained to fight dirty wars (it probably says something about Moore’s attitude that a condition of the U.S. Army’s cooperation in making the movie was that Moore not be involved in any way).

But Wayne – who’d never served in the military – saw Moore’s book as a vehicle to rebut all the long-haired, dope-smoking, flag-burning, unAmerican peaceniks making such a hell-no-we-won’t-go ruckus on college campuses at the time. With the logistical support of an approving U.S. Army, he set about making an outrageously simplistic rah-rah picture of a war that, by the time of the movie’s release, was not only going badly, but tearing the country apart.

Moore’s book is constructed as a series of stand-alone stories linked only by their all involving members of the Berets. Barrett’s script takes a couple of those stories, combines elements of a few more into a single, wandering plotline following anti-war journalist David Jansen as he takes up Beret colonel Wayne’s invitation to go to Nam and get the straight poop on what’s really happening in the war. Jansen’s there for a large-scale Viet Cong night assault on an American firebase, and then later drops out of sight as the movie clumsily transitions to a behind-the-scenes mission to capture a North Vietnamese general.

[one_half]

To be fair about this, let’s put the movie’s inflammatory politics aside. Let’s just talk movie-making. Even at that level, we have to talk astoundingly bad.

For a project made with expansive support from the Army, the movie, at times, looks shockingly cheap. During the attack on the firebase, even in the dark, it’s obvious that a lot of those Cong storming the wire are white guys in blackface. Some of their equipment is a little dodgy, too. One of my favorites – watch the battle sequences closely, you’ll see it – is one of them carrying an old-fashioned tommy gun, the kind with a pistol fore grip, but with the magazine removed in the hope (I guess) nobody’d be able to tell it’s a tommy gun.

A particularly crappy part of the night battle is a scene where Wayne’s chopper is hit. Even for the time, it’s painfully obvious they’ve set a small model on fire. Then, when the movie cuts to a life-sized burning chopper for the actual crash, you can see the restraining strap unfurl as the wreck is released to the ground. That’s not just bad; that’s bush league.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

Wayne uses a visual that didn’t make much sense in his previous directorial disaster, The Alamo (1960); having a mass of the enemy, standing shoulder to shoulder, slowly stalk forward into blazing guns with hardly a one falling. Just as dumbfoundingly nonsensical, later, when a U.S. gunship strafes the Cong who’ve overrun the camp, they seem to be standing around stock-still waiting for the squibs to go off.

If you want a stark measure of how badly put-together the movie is, measure its helicopter attack sequence against a Cong bridge against the majestically terrifying chopper ballet Francis Ford Coppola put together in Apocalypse Now (1979).

Barrett’s script – politics aside – is equally sloppy, and not just with that plotline which feels like two movies (the firebase attack; the behind-the-lines operation) shotgun-wedded together. Every tired WW II war movie cliché you can think of is hauled out and run in front of the camera: the conniving scrounger with a secret heart of gold glommed onto by an adorable orphan whose only friend is his scruffy little pooch; the burly, gruff veteran sergeant; the critical newspaperman who doesn’t have to know what he’s talking about to have a completely wrong opinion. Those cliches look all the more tired misplaced as they are in the context of a war that was, in every way, the antithesis of WW II. I mean, c’mon; the little orphan boy? With a puppy? The only old corndog missing from the script is the one about somebody’s sister who needs an operation so she can dance the ballet again.

[/one_half_last]

No matter how you cut it, no matter how politically blind you want to be, it’s a dumb movie with characters saying dumb things (“Out here, due process is a bullet!”), and a director (and keep in mind, God bless ‘im, I loved John Wayne) doing even dumber things.

So, what’s my fascination with it? What keeps bringing me back?

Part of it is the fun of watching a 1940s kind of patriotism mash up against the war that killed that kind of sensibility. As I sit there, about every five minutes I’m compelled to say out loud, “Seriously? Seriously?” Part of it is that I’ve always had a fondness for old war movies, and that’s exactly what The Green Berets is – an old war movie disguised as a Vietnam War treatise.

But undoubtedly the biggest attraction for me is watching John Wayne be John Wayne no matter how wrongheaded the context. Look, he was 30 years and 50 pounds past pulling off the part (there are scenes of him in a dress uniform where it looks like his buttons will pop so hard they’ll take somebody’s eye out across the room), and his take on the war came out of some Leave It to Beaver dream state worldview, but, ya know, he was still John Wayne…and, like I said, I loved the guy.

[callout]

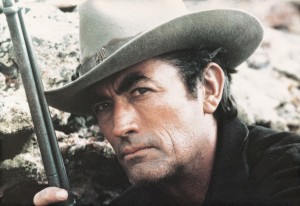

Mackenna’s Gold (1969). Directed by J. Lee Thompson. Adapted from the novel by Heck Allen by Carl Foreman.

[/callout]

The pedigree promised big. Thompson, after all, was the guy who’d directed 1961’s huge hit, The Guns of Navarone. Here he was re-teamed with Foreman who had produced and written the screenplay for Navarone, and was taking on the same roles for Mackenna. It was a big-scale production originally intended for Cinerama, and its leads – Gregory Peck and Omar Sharif – were backed by an all-star supporting cast including – among others — Raymond Massey, Burgess Meredith, Lee J. Cobb, Eli Wallach, Edward G. Robinson.

Loosely based on the legend of the Lost Adams Diggings, the story has Peck as a marshal in the Old West who learns from a dying Apache about a secret canyon loaded with gold. Peck doesn’t believe the story, but everyone else does, including Omar Sharif as one of those grinning Mexican banditos who lives in a permanent state of toothy amusement over everything including theft, kidnapping and murder. Sharif forces Peck to take him to the canyon. On the way, they acquire a snowballing mob of gold-hunters.

[one_half]

From the first sonorous tones of Victory Jory’s narration, it’s clear Thompson/Foreman are out to tell an epic, definitive story about corrupting greed. Instead, what they turn out is a bloated, cliché-ridden, often silly tale – bloated, cliché and silly enough to make you forget these were the guys who turned out a classic actioner like Guns of Navarone.

Like The Green Berets, this is a flick which, despite its grand-scale production, still manages, at least at times, to look surprisingly cheap. It’s bad enough the cast isn’t riding real horses for their close-ups, but they’re also filmed in front of an exceptionally lousy back projection.

Or take that all-star line-up, most of which are billed under the heading, “The Men of Hadleyburg.” The idea is supposed to be that even all these decent folk (one’s a judge, another’s a preacher, etc.) can fall victim to gold fever. They show up en masse, they have one scene around Sharif’s campfire where they shamefacedly admit to their greed, and then they’re all – I’m not kidding, all – killed off in the very next scene during an Apache ambush.

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

One of my favorite bad scenes happens after the surviving fortune-seekers discover the secret canyon. An unarmed Peck and Camilla Sparv (the Swedish cutie is shoehorned into the love interest role looking as at-home in the Old West as a Japanese tea house) try to escape by climbing a sheer, several hundred-foot high cliff to some abandoned Indian dwellings (which, by the way, they do with a quickness I’m sure has Edmund Hillary pulling a WTF!!! spin in his grave). Sharif gives chase up the same cliff. Every time I watch this I keep thinking, Hey, Greg, just drop a rock on the guy’s head! At least step on his fingers when he tries to climb up. But noooooo! That would make too much sense.

It gets worse.

[/one_half_last]

Peck and Sharif fight. Peck beats the crap out of Sharif but doesn’t kill him. Never occurs to him to, say, chuck him off that cliff once he’s got him down. Good guys don’t do that, I guess. Instead, Peck and Sparv now climb all the way back down that several hundred-foot high cliff. And, yeah, Sharif follows. So, scale a cliff, fight, climb back down, and none of them are even breathing hard.

Also like Berets, the whole movie feels old and tired. Mackenna came out the same year as Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and The Wild Bunch, and next to these two energetic exercises in Old West revisionism, Mackenna comes off about 20 years out of date.

You want a Western about greed? One that’s more than a half-century old yet still hasn’t dated? John Huston did it with a modest budget and just three guys digging small handfuls of gold dust out of a mountain in Mexico in Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948). Managed it quite well, in fact. I believe the word “classic” is usually used.

So, what keeps bringing me back to Mackenna’s Gold? I think of the big name talent involved, look at what they wound up with, and wonder how this pool of normally capable filmmakers managed to get abso-freaking-lutely nothing right.