Written and directed by Joann Sfar

2010, France

Joann Sfar’s Gainsbourg (Vie héroïque) could well lay claim to being one of the longest cigarette commercials in movie history. In this smoke-filled take on the life of singer, songwriter and French icon, Serge Gainsbourg, even the fish in the animated opening credits sequence are puffing away. With a nod perhaps to Sylvie Simmons’ aptly titled 2003 biography, A Fistful of Gitanes, this unconventional biopic offers an emphatic two-fingered Gallic riposte to those who would like to see fags airbrushed from cinema.

Gainsbourg, who died in 1991, aged 62, doesn’t enjoy the worldwide recognition of other 20th-century musical giants like Bob Dylan, John Lennon or Elvis Presley. I was aware of him as the father of actress and singer Charlotte Gainsbourg, and for duetting with her mother Jane Birkin on the scandalous and very silly “Je t’aime . . . mois non plus”. Oh, and he had an affair with Brigitte Bardot in the 60s. If you’re not already a fan, it’s worth familiarising yourself with the face of the man born Lucien Ginsberg, if only to marvel at the brilliant performance of actor Eric Elmosnino, who plays him as an adult.

Sfar, who like Gainsbourg is Jewish, is well-known as a graphic artist but had never directed a film before. He treats the boyhood of Lucien (appealingly played  by Kacey Mottet Klein) in Nazi-occupied Paris as a series of comic misadventures. This may come as a relief to those weary of the “rags to riches to ruin” approach familiar from films like Ray and Walk the Line. So, we admire the chutzpah of young Lucien as he rushes to be the first to collect — and display — the official yellow star that proclaims his Jewishness. Despite a brusque rejection from a girl who labels him as “ugly”, and the posters crudely mocking his features, Lucien is sustained by his early passion for painting, his disrespect for authority and his wholehearted appreciation for the female form.

by Kacey Mottet Klein) in Nazi-occupied Paris as a series of comic misadventures. This may come as a relief to those weary of the “rags to riches to ruin” approach familiar from films like Ray and Walk the Line. So, we admire the chutzpah of young Lucien as he rushes to be the first to collect — and display — the official yellow star that proclaims his Jewishness. Despite a brusque rejection from a girl who labels him as “ugly”, and the posters crudely mocking his features, Lucien is sustained by his early passion for painting, his disrespect for authority and his wholehearted appreciation for the female form.

Sfar’s most audacious move is to give his hero an alter ego in the form of a cartoon boy with an outsize head, four hands and features that caricature his Jewishness. Lucien is packed off to the country to escape the Nazis, where he dazzles everyone with his sexually explicit sketches. But his corpulent friend shows up there, too, underlining his inability to distance himself from his “ugly mug”. Later, the adult Serge has to contend with a grotesque, long-nosed figure (played by Doug Jones) that looks and acts like his very own Gerald Scarfe (http://www.geraldscarfe.com/ ) cartoon.

Sfar’s most audacious move is to give his hero an alter ego in the form of a cartoon boy with an outsize head, four hands and features that caricature his Jewishness. Lucien is packed off to the country to escape the Nazis, where he dazzles everyone with his sexually explicit sketches. But his corpulent friend shows up there, too, underlining his inability to distance himself from his “ugly mug”. Later, the adult Serge has to contend with a grotesque, long-nosed figure (played by Doug Jones) that looks and acts like his very own Gerald Scarfe (http://www.geraldscarfe.com/ ) cartoon.

You would expect a film about Gainsbourg to celebrate the wit, the women and the songs. In interviews Sfar has said that he conceived the project primarily as a musical and that he aimed for an

The bulk of the movie plays out like the ultimate male fantasy, interspersed with moments of introspection: our hero moves from small-time piano player in a cabaret; to dallying with sultry Juliette Gréco (Anna Mouglalis) to the strains of “La Javanaise”; and writing innuendo-laden pop songs for teenager France Gall (Sara Forestier). Gainsbourg’s life is almost entirely dominated by women — lovers, wives, his Russian mother — but it’s Brigitte Bardot and Jane Birkin who make the biggest impact here.

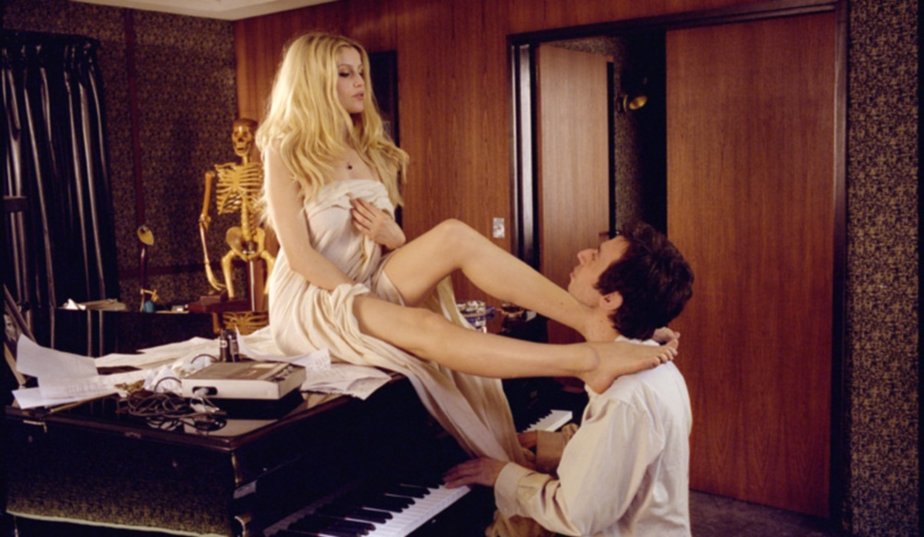

As Bardot, the gorgeous Laetitia Casta proves rather more adept at erotic dancing than providing vocals for the duet of Bonnie and Clyde. I think that was the point, though. Who wouldn’t be inspired to new heights of creativity by the sight of the ultimate French sex symbol sashaying down a corridor in thigh-length boots or draped over a piano dressed only in a sheet? They find time to smoke a few cigarettes in between the intervals of l’amour.

English actress Jane Birkin (played here by Lucy Gordon) eventually became Gainsbourg’s third wife, and is perhaps the one woman in this film who offers him qualities beyond the merely decorative and seductive. That said, it’s hard not to judge the soulful performance of Gordon in the light of her tragic death, just weeks after filming was completed. Together, Jane and Serge released the notorious heavy breather, “Je t’aime . . . mois non plus”, though the film is surprisingly brief in its depiction of the making and subsequent banning of this oft-recorded number.

The last half hour of the film drags badly, with a succession of scenes — including the death of Gainsbourg’s father — that feel like endings but aren’t. Sfar doesn’t offer dates, locations, or many clues as to which decade in the life of the artist we’ve reached. It probably helps if you’re familiar with the history of French pop and politics, so that you know his controversial reggae version of “La Marseillaise” was recorded in Jamaica the late 70s. It demonstrated Serge’s life-long capacity for embracing new musical styles and courting controversy.

Sfar has said that he didn’t want to depict a man who “learns things” and he’s certainly avoided the preachiness, sentimentality and predictable plotting that reduces the lives of rebel musicians to mere cautionary tales. To learn more about this flawed genius and cultural icon you’ll need to read a few books, download some tunes and, perhaps, crack open a pack of Gitanes.

– Susannah Straughan

http://notreallyworking.wordpress.com/