The problem, if there is one, can be treated etymologically – i.e. by unpacking the significance of Eisner’s key cri de guerre. When Eisner returned to comics in 1978 after a prolonged absence, he described his new work (the justly celebrated A Contract with God) as a “graphic novel”. This loaded term lent just the right note of gravitas to the piece, and provided a canny marketing angle that remains powerful today. But what does it really mean? Does the use of drawings, arranged in panels and separated by gutters, make Eisner’s collection of tenement tales any more “graphic” than a book which relies primarily on words (which are also composed of little pictures that we call letters)? And what’s so prestigious about novels, anyway? If you’ve ever taken an intro to Canadian Lit class, you’ve probably been forced to read Wacousta. Wacousta is a novel. It is a very, very bad novel. And it’s not the only one. If Eisner had tried to call A Contract With God a “Graphic Wacousta”, we’d have been free of this mess long ago. This isn’t just a question of semantics either (the fundamental insight of postmodern theory is that nothing is ever just a question of semantics). By trading on the imagined grandeur of “the novel” (and not merely for marketing purposes), graphic novelists like Eisner risked losing contact with the unique strengths of their own medium.

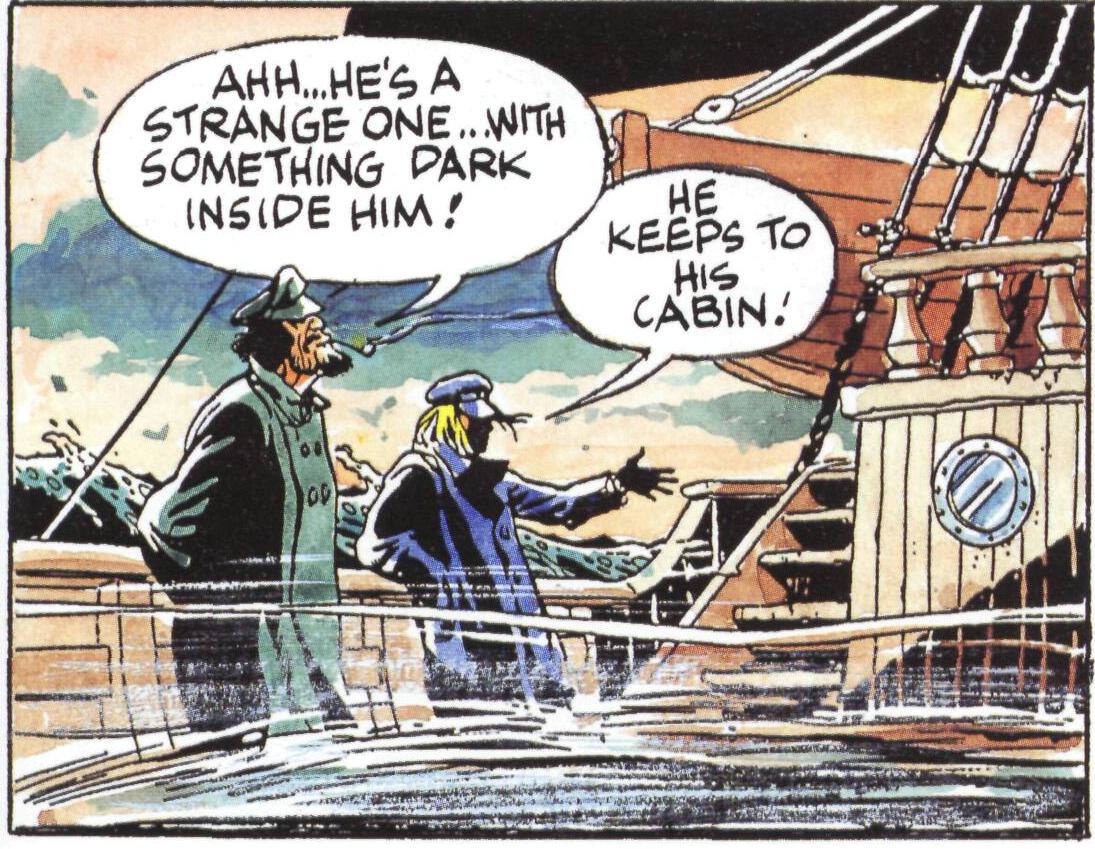

That’s not to say, of course, that all works of art marketed as “graphic novels” suffer from this failing – Ware’s aforementioned Jimmy Corrigan is a prime example of a piece that pushes beyond the traditional limits of the comic book through formal innovation, rather than simply by exploring thematic terrain traditionally associated with literary fiction. Unfortunately, Eisner’s later work is less successful in avoiding the latter snare. Nowhere is this more evident than in his 1998 gloss on Herman Melville’s Moby Dick – one of the most notoriously un-adaptable novels ever written. Eisner’s piece slams up against many of the same obstacles that sank John Huston’s 1956 film. The comic, like the movie, reduces the story primarily to an adventure yarn – which wouldn’t be such a bad thing, if Ahab’s zealous pursuit of the eponymous white whale was actually thrilling on its surface.

But it’s not.

Eisner’s decision to present panel after panel of blow by blowhole action, accompanied by fairy tale style captions derived very loosely from Ishmael’s novel-narration, fails to reach the philosophical wellsprings of Melville’s narrative. Eisner’s whale never becomes anything more than a particularly cunning beast who has wronged the one-legged captain of the Pequod. In the original work, Moby Dick is so much more than that. He is a symbol for all wrongs done to every being in creation. Ahab’s vendetta is not a personal one – it’s a (doomed, of course) quest to eradicate evil from the universe. And Melville makes us at least partially complicit in that mad metaphysical spree by using every literary trick in the book (shifts from subjective to objective narration, Shakespearean soliloquies, insanely detailed plunges into the minutiae of mid-19th century whaling practices, etc). But Eisner leaves his innovator’s toolbox unopened on a shelf in his “disreputable” past (as many have noted, The Spirit is a treasure trove of still-startling techniques for building atmosphere and tension, and all with an ironic edge that is entirely lacking here). The book certainly tells a competent story, and Eisner remains at his best when depicting the fog-and-storm enshrouded ship, or kinetic details like the spiraling action of a harpooner’s rope; but, ultimately, this “graphic novel” is far more prosaic than the prose work it is based upon.