Jiji, I’ve decided not to leave this town. Maybe I can stay and find some other nice people who will like me and accept me for who I am.

In a month full of horror and malevolent covens and blood-curdling scares, I offer now the soothing respite of Hayao Miyazaki’s beautiful and serene Kiki’s Delivery Service. Possibly Miyazaki’s most under-appreciated film, it is surely his most modest, which I mean as a compliment. It is the epitome of Miyazaki’s quiet filmmaking, letting the soft emotion and warm aesthetics of the animation do most of the talking. The fact that Kiki is a witch is beside the point, because this is a coming-of-age story for a young girl committed to helping others but forgetting about herself.

Coming-of-age films for girls are rare enough as it is, and with Kiki’s Delivery Service coming as it did in 1989 and treating the subject with such earnest compassion (as Miyazaki’s films always treat their young female characters), it shines for its genuine honesty in dealing with the subject through the complex lens of Kiki’s character. Kiki is not perfect, and neither is the world around her. She is hotly jealous of the rich girls in the community, and is helpful to others to a fault. In her self-examination, she finds her flaws and learns to embrace them.

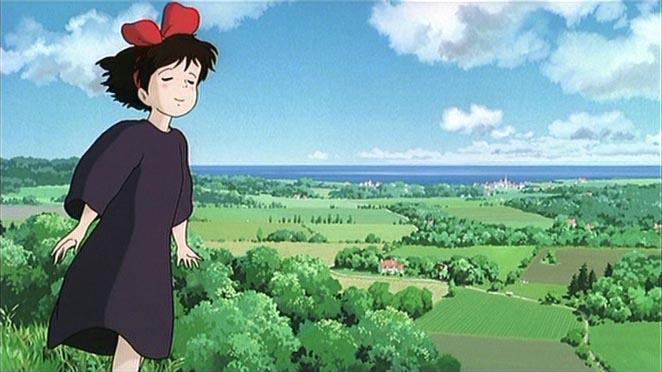

It’s a film that is honest about its protagonist, and interested in the spectacle that can be found in quiet soul-searching within gorgeous seaside villages (magnificently animated, as always with Studio Ghibli). It also lacks an antagonist, or really much conflict at all. A significant part of the film’s charm is how effortlessly engaging it is while remaining so amiable and low-maintenance. It’s the rare film that can be described as perfect to fall asleep to and have it be a positive assessment. This only means that it has such beauty, and such an easygoing and pleasant manner, so that you can get lost in this idealized world and fall into a sublime daze.

If I lose my magic, that means I’ve lost absolutely everything.

The film is very much about Kiki’s vulnerability. As a witch, she must go out on her own and learn to be independent as a kind of training. The parallel of normal young girls (and boys) moving away from home is obvious. She is in a vulnerable state as she tries to settle into this self-reliance, and to encounter the real world and its many problems waiting to be solved. Her doubts about herself, especially after losing her ability to fly, are tantamount to understanding the film’s message about vulnerability. By taking on the help of others (for once), she realizes that she can learn from her vulnerabilities and that sometimes it’s okay to accept the assistance of others, without sacrificing your independence.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Kiki’s Delivery Service isn’t a horror film whatsoever, but it does have a standing within the history of witchcraft in film. Witches are most often associated with black magic and the occult, but there is a certain subgenre of witches as healers (usually referred to as “white witches”, which I will leave there without comment). They are often witch doctors, entrenched in a medical history of women healers being demonized by the industrial monopolization of healthcare over the last few centuries. This has manifested itself in films as varied as White Witch Doctor (1953) and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006). It’s in this vague tradition (focusing on the healing and helping, not the possible aura of evil) that Kiki’s witchcraft follows in, married with some more common witch stereotypes out of Sabrina the Teenage Witch, like Kiki’s talking black cat, Jiji, and her ability to fly on her broomstick.

How come you never told me you were growin’ up so fast?”

Witchcraft, as ever, is used as a framing tool in order to tell the real story about Kiki finding out about herself. Her character is beautifully written, arguably with more nuance and warmth than perhaps any other animated character before or since. By starting up her delivery service, she takes the initiative to use her gifts for good and to establish herself as a self-sufficient girl in the real, adult world. Thankfully, most of the people she meets are just as kind-hearted and delightful, so her journey of self-discovery is more ambiguous until she starts to lose her powers. She falls into a depression, feeling lost and without a purpose, mirroring her lack of confidence and fear of being out on her own. That is, until it’s up to her to save the day, and she simultaneously gets her ability to fly back and does away with her self-doubt. She continues to be unable to talk to Jiji, though (in the original version of the film), suggesting her steady move into adulthood.

Kiki, in other words, wants to find her individuality, but within the structures that exist in her community and her culture (whether in terms of witches or Japan). She is encouraged to go out on her own, but she makes the choice. She is reluctant to accept the help of others and lacks self-awareness for when she needs it, but ultimately realizes her mistake. She is wrangling with this idea of herself, with her identity and who she wants to be, at times sure of herself and at others, not so much. It’s a balance we all deal with, made all the more pertinent when she begins to lose these products of her childhood and her past innocence (talking to Jiji), all she’s known until now, as part of that grappling. We may not suddenly realize we can no longer talk to our cat, but we certainly run headfirst into things that are no longer acceptable once you grow up, or new things that are now your responsibility. We see Kiki in ourselves, and she is so resourceful, so warm, so happy and confused, barrelling toward adulthood with all the grace of a Miyazaki girl, poised and strong, ready to take on the entire world.